The EU Digital Markets Act

Article updated: February 6, 2024

I. Introduction

“We are a utility,” said Mark Zuckerberg about his company Facebook in 2012.[1] A decade later, EU legislators appear to deliver what Zuckerberg (unwillingly) called for: being regulated like a utility. On 1 November 2022, European a new landmark Big Tech regulation, the Digital Markets Act (“DMA”), entered into force and will apply from 2 May 2023.[2] The law imposes specific obligations on the world’s Big Tech firms, which it labels ‘gatekeepers.’ The Gatekeepers must comply with the DMA by March 2024.

The DMA comes after years of rapid growth in the tech sector which is today dominated worldwide by a few firms summarized as “GAFA” (Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple). Their size and corresponding conduct triggered numerous antitrust actions in Europe and the United States, but with limited success. Standard antitrust law is now understood by many to be insufficient and too slow in the face of the Big Tech giants. For example, the EU Commission opened a major antitrust investigation against Google with regards to its Shopping practices in 2010.[3] However, it took 7 years to issue a formal decision[4] and another 4 years for the General Court of the EU to decide on Google’s appeal.[5] The case is currently on second appeal at the Court of Justice of the EU,[6] while Google is still not complying with the Commission’s 2017 orders. In the fast-paced world of digital technology, such a ‘lost decade’ means lost opportunities and markets with sustainably weakened competition. In short, competition law appears to deliver “too little, too late.” To solve this issue, the DMA is supposed to enable quick enforcement action in the EU, through precise ex ante obligations that do not allow for years-long discussions and appeals.

The DMA’s stated aim is to create ‘fair and contestable markets’ (Art. 1(1)).[7] Although this may sound like an antitrust bill, the EU keeps emphasizing that it is not. For reasons rooted in the arcane system of shared legislative competences between the EU and its member states, the EU had to pass the law formally as a piece of sectoral regulation aimed at harmonizing the internal market—and explicitly not as an antitrust bill.[8]

In the bigger picture, the DMA is only one piece of the mosaic that is the EU’s grander digital strategy, which also includes the following bills:

- The Digital Services Act, a law aimed at specific online harms, such as hate speech, dark patterns, and related platform liability.

- The Data Act, which includes rules on data portability and data licensing contracts.

- The AI Act, targeted at ensuring the integrity and security of algorithms.

- The Data Governance Act, an ‘umbrella regulation’ which is supposed to pull all strings together. While some mosaic pieces overlap, they are supposed to be mostly complementary.

In the US, numerous similar proposals have been put forward, but they yet await final approval.[9]

II. What is a ‘Gatekeeper’?

The DMA’s obligations apply only to gatekeepers, one of the key terms of the DMA. Gatekeepers are defined as undertakings that provide ‘core platform services’ (another central term) and that have been designated as such by the EU Commission (Art. 2(1)).

Core platform services are defined to encompass most of today’s major digital services (Art. 2(2)):

- Search engines and other online intermediation services;

- Social networks, video-sharing platforms, and other interpersonal communication services;

- Operating systems, web browsers, and virtual assistants;

- Cloud computing services; and

- Online advertising services such as ad exchanges.

The Commission will designate gatekeepers as such if they satisfy the following conditions (Art. 3):

- A significant impact on the EU market: this condition is presumed if the undertaking’s annual revenue exceeds 7.5bn EUR or has a market capitalization in excess of 75bn EUR.

- Its core platform service is an important gateway for business users to reach end users: this condition is presumed if the undertaking has at least 45m monthly users and at least 10,000 yearly active business users in the Union.

- An entrenched and durable position in its operations: this condition is presumed if the undertaking satisfied the conditions above in each of the three years prior to designation.

In September 2023, the European Commission designated six gatekeepers under the Digital Markets Act, Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta, and Microsoft.

III. Obligations

1. Overview

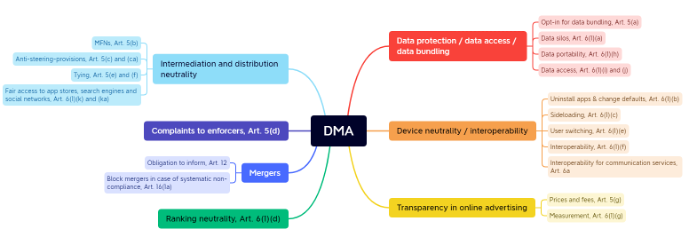

Upon designation, gatekeepers have 6 months to comply with a set of specific obligations (Art. 3(8)). The obligations are divided into two groups, a ‘black’ list of per se obligations that apply without specification (Art. 5), and a ‘grey’ list containing obligations that may be specified further by the Commission (Art. 6 and 6a).

The obligations cannot—except when explicitly mentioned—be justified on grounds such as efficiency or privacy gains. This is an important difference to ‘standard’ EU competition law obligations pursuant to Art. 101 and 102 TFEU.

The obligations are rather specific and tailored to concrete cases. The DMA has been criticized for being static and unresponsive to future technology for this reason[11] – but the Commission has the power to update those obligations pursuant to Art. 10, enabling it to adapt to new products and business models.

The obligations can be grouped into 7 themes, as illustrated below:

2. Obligations in detail

We will examine each theme in more detail by looking at one or two examples, focusing on select obligations:

Theme 1: Data protection, data access & data bundling

Art. 6(1)(a) contains an obligation for gatekeepers to refrain from using their business users’ data against them.[12]

This provision was likely inspired by one of the Commission’s proceedings against Amazon. The Commission is currently investigating Amazon’s practice of using third-party merchants’ data to replicate their most successful products and possibly drive them out of the marketplace.[13] As is the case with other DMA obligations, this one is modeled specifically to prevent such conduct.

In terms of data, further essential provisions grant business users rights to access gatekeepers’ data, for example search engine data (Art. 6(1)(i) and (j)). Those provisions are aimed at creating a level playing field in areas where Big Data behemoths like Google have a head start and third parties can hardly catch up. This way, other search engines may be able to retrieve Google’s search data.

Theme 2: Intermediation & distribution neutrality

The DMA includes a number of provisions addressing the fair distribution of digital products on platforms. The Commission had received numerous complaints about platforms that allegedly abused their bottleneck power that stems from controlling access to millions of users. For example, Spotify had complained that it cannot conclude contracts and execute billing on its own terms with Apple users – it has to use Apple’s In-App Payment system.[14] Apple charges a fee of 30%, perceived by many app developers as too high. This “App Store tax” triggered further complaints in the Netherlands[15] and a much-debated court filing in the US by Epic Games.[16] The DMA contains rules prohibiting such anti-steering provisions (Art. 5(1)(c)); tying arrangements (Art. 5(1)(e)); and obligations to allow third-party app stores (Art. 6(1)(c)). It also establishes a right to so-called ‘FRAND’ access to app stores (Art. 6(1)(k)).

Essentially, these provisions aim at loosening the grip of large platform and operating system providers such as Apple and Google on their ecosystems. The DMA wants those platforms to be open to third-party apps and app stores, in order to enable users to get their apps from any source possible. Apple’s CEO Tim Cook was vocal about those rules endangering the integrity and security of iOS,[17] which is presumably why the DMA’s final version includes a specific clause allowing gatekeepers to reject third-party services for integrity or security concerns (Art. 6(1)(c)).

Theme 3: Device neutrality & interoperability

There are further ways in which the DMA attempts to open up ecosystems. Gatekeepers are obliged to ensure that users can un-install apps on operating systems, virtual assistants, and web browsers.[18] Users must be allowed to change default settings for services such as search engines, an antitrust problem dating back to the early Microsoft cases.[19] Gatekeepers will also be required to implement a choice screen, allowing users to choose between proprietary and third-party apps.[20] For example, Google asks Android users to choose between Google, Bing, DuckDuckGo or Ecosia as their default search engine. Google had implemented this choice screen only after the Commission had fined it EUR 4.34bn.[21] The DMA will likely lead to more of such choice screens for consumers in the future.

Moreover, gatekeepers will be required to open up their messaging services (“number-independent interpersonal communications services”). Gatekeepers will have to provide interoperability between their services and those of third parties (Art. 6a). This could mean that soon, you might be able to message your friends on Facebook from your LinkedIn account, or Signal users from WhatsApp.

Theme 4: Ranking neutrality

One of the most-watched antitrust cases in the past years was the Commission’s case regarding Google Shopping. Google had introduced a comparison shopping service that allowed searchers to quickly compare products and prices in a OneBox on top of the Google search results page. Google demoted the sites of competing services to the far end of the results page, depriving them of indispensable traffic. In response, the Commission ordered Google to treat competing comparison shopping services equally to its own.[22] This ruling came to be known as a prohibition of ‘self-preferencing.’ With its decision, the Commission answered a fundamental question: should search engines be open to third-party services, or evolve into proprietary services where all offerings are delivered by one supplier (Google)? The General Court of the EU confirmed the Commission’s decision for search engine neutrality in 2021.[23] Google appealed the decision to the Court of Justice of the EU, and a final decision is expected by 2023.[24] The DMA now confirms the Commission’s view by including a prohibition of self-preferencing in Art. 6(1)(d).[25]

This provision will apply not only to comparison shopping services, but also to numerous other specialized vertical search engines that Google allegedly attempted to exclude, such as job boards, flight search sites, or travel portals.

Theme 5: Transparency in online advertising

Google today still generates more than 200bn USD or 80% of its revenue from online ads.[26] Critics claim that those sky-high earnings are monopoly rents, generated from Google’s dominant position in the sale of online ads. According to the UK’s enforcement agency CMA, Google monopolized the ad tech sector and commands market shares above 50% in each step of the supply chain.[27] The Commission also opened an investigation in 2021.[28] One Google senior executive admitted, “[t]he analogy would be if Goldman or Citibank owned the NYSE.”[29]

During investigations, regulators noticed that they could hardly discern how much money Google made out of its ad tech transactions because it did not fully disclose prices and fees to customers.[30] Google is estimated to capture twenty to forty percent of any given ad sale—a very imprecise range, in particular in a digital market where all transactions are recorded precisely.[31] Also, Google’s ad customers cannot independently measure the success of their ad campaigns because Google allegedly withholds necessary data.[32] Such disregard for customer needs and basic transparency is only feasible because there is no way around Google in online advertising.

As a response, the DMA obliges ad tech providers such as Google to give full information on prices and fees (Art. 5(g)) and to provide its customers with the data that are necessary to perform independent measurement (Art. 6(1)(g)).

Theme 6: Mergers

Mergers have been a big concern for regulators in the tech sector. The GAFA have acquired more than 400 firms in the decade between 2009 and 2019.[33] Many of those are thought to have been ‘killer acquisitions,’ transactions that only serve the purpose of shutting down the target firm to eliminate a competing service. Also, the sheer number of transactions and the accompanying unprecedented size of Big Tech firms have raised eyebrows among enforcers. Yet, many of them saw themselves empty-handed because numerous mergers did not pass notification thresholds. Thresholds focus on revenue, not transaction value, which is a problem when nascent firms have a highly valuable future product but do not yet generate significant revenue. Using this loophole, Big Tech firms could acquire hundreds of firms ‘below the radar’ of merger review.[34] The US FTC and DOJ are currently reviewing their merger guidelines to account for those problems. The DMA provides a two-fold response:

- First, gatekeepers are obliged to inform the Commission of all planned transactions prior to their consummation. If a member state authority deems a transaction harmful, it can prompt the Commission to review the case, using the Art. 22 EUMR referral procedure[35] (Art. 12(3a)).

- Second, the Commission can impose an outright ban on all transactions of repeat offenders. Such ‘systematic non-compliance’ can be found if a gatekeeper violates the same or similar obligations twice in a period of 8 years (Art. 16(1a)).

IV. Enforcement

The Commission will be the main enforcer of the DMA. Member state authorities have been sidelined to a backbencher position. They are involved through the European Competition Network and in the DMA ‘High-level group,’ which only has a consulting function (Art. 31d). Beyond that, member state authorities and the Commission are obliged to inform each other about relevant work (Art. 31a, 31b). National authorities may, however, investigate breaches of the obligations on their own if the Commission does not act (Art. 31b(7)). In any case, though, national decisions must not run counter to the Commission’s decisions (Art. 1(7)).

The Commission can make use of the full arsenal of the enforcement powers that is also relies on in standard antitrust, cartel, and merger investigations, such as RFIs (Art. 19), inspections (Art. 21), and commitments (Art. 23). It can also carry out market investigations to prepare a full procedure (Art. 14-17 and 33). In cases of urgency, the Commission may impose interim measures (Art. 22). All decisions are subject to review by the EU courts (Art. 35; Art. 261 TFEU).

Gatekeepers are obliged to create specific compliance departments within their firms and install risk management systems (Art. 24b).

The heft of the DMA lies in the fines. The Commission can impose fines of up to 10% of the gatekeeper’s annual worldwide turnover, and a whopping 20% in cases of systematic non-compliance (Art. 26).

V. Outlook

Will the DMA deliver on its promises?

Today’s digital revolution has been compared to the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century. In 1890, US Congress responded to adverse marketplace effects by enacting the first modern antitrust bill, the Sherman Act, modelled for the industrial economy.[36] The law shaped the US economy, inter alia, by breaking up American Tobacco, Standard Oil, and AT&T. Is the DMA the “Sherman Act 2.0” for the digital economy?

If so, it would need to achieve its key aim: to speed up the process of reaching final decisions. This is intended to be done through making obligations more precise and giving less room for debate. Margrethe Vestager, the EU’s Competition Commissioner, framed it in this humbling way:

“You could think of our work, as a competition authority, as being a bit like clearing out the rubbish that’s been dumped in a river, to keep it flowing smoothly and well. And with the Digital Markets Act, it’s rather as though a sort of filter is being installed, a little way upstream, which removes some of that debris before it gets to us. It won’t change our powers – but its presence does mean that we won’t have the same problems to deal with in the future. It means some kinds of behaviour simply won’t reach us – because the Act will make sure that those things don’t happen.”[37]

How does this plan compare to the legislative timeline? Gatekeepers have to comply with the DMA by March 2024. From that point on, the DMA is supposed to be ‘self-executing.’[38] Yet, given the GAFA’s past “hesitance” to comply with the antitrust laws, it is more likely that gatekeepers will not comply voluntarily. The EU Commission will have to issue non-compliance decisions[39]. However, those decisions will likely not be final. Decisions by the Commission determining non-compliance with a DMA obligation can be appealed (Art. 35), and considering Big Tech’s current legal strategies, appeals are very likely. Appeals to the EU General Court and the Court of Justice of the EU take around 6 years.[40] Thus, decisions may be legally binding only as late as 2030.

The DMA’s authors may object that the Commission is able to impose interim measures, enabling speedy enforcement (Art. 22). However, interim measures face two challenges: first, the Commission used that instrument only once in the past two decades.[41] Since the wording of Art. 22 DMA is quasi-identical to that of the existing interim measures provision in standard competition law (Art. 8 Regulation (EU) 1/2003), it is difficult to question why the Commission should change course suddenly with the DMA. Second, the EU Court of Justice can suspend the application of interim measures that are under appeal.[42] This may render interim measures ineffective until appeals procedures are completed.

Despite EU officials labelling the DMA as being adopted in record time, some competition experts are skeptical that this is the dynamic solution that the digital economy needs.

What else are competition lawyers discussing about the future of the DMA?

The DMA and member state laws

One issue is the DMA’s relationship with EU member state laws. In particular, Germany enacted § 19a ARC[43] in 2021, a provision that contains similar obligations for gatekeepers. Usually, EU law prevails over national laws,[44] but the Germans would like to apply their new law despite the DMA. As a result of political compromising, Art. 1(5) contains a cryptic demarcation of competences:

“In order to avoid the fragmentation of the internal market, Member States shall not impose on gatekeepers further obligations by way of laws, regulations or administrative action for the purpose of ensuring contestable and fair markets. Nothing in this Regulation precludes Member States from imposing obligations, which are compatible with Union law, on undertakings, including undertakings providing core platform services, for matters falling outside the scope of this Regulation, where these obligations do not result from the relevant undertakings having a status of gatekeeper within the meaning of this Regulation.”

The DMA and ‘standard’ competition law

Another point of discussion is the DMA’s relationship with ‘standard’ competition law. Art. 1(6) clarifies that the DMA is without prejudice to the application of Art. 101 and 102 TFEU, the EU’s cartel and monopolization provisions (similar to Sec. 1 and 2 Sherman Act). Also, in the recent bpost judgement, the Court of Justice of the EU decided that one conduct may be fined twice: once based on competition law and once based on sectoral regulation. The court saw no violation of the ne bis in idem principle (‘double jeopardy’).[45] The judgment may allow parallel cases – one based on the DMA, one based on standard competition law.

Private enforcement

EU competition lawyers are split into two camps on the issue of private enforcement. Some say there will be none, as the DMA does not include rules on private enforcement, although that was discussed during the legislative procedure. Private enforcement of standard competition law has only really taken off in the EU after specific rules were introduced in the 2014 Cartel Damages Directive—and the DMA lacks comparable norms. Others—including the EU Commission—believe specific rules are not necessary and that private enforcement is feasible without them.[46] As the DMA is a Regulation and hence directly applicable,[47] firms can invoke the DMA in member state courts with ancillary claims based on member state law, such as tort law. Furthermore, contracts that contradict the DMA will be void—which member state courts can determine as well as the EU courts and the Commission.[48] Lastly, the DMA provisions can also be enforced through representative actions based on the EU collective redress directive.[49] These theories will likely be tested in the coming years. With regard to Germany, Eleventh Amendment to the Act against Restraints of competition introduced provisions to facilitate private enforcement of the DMA.

The DMA is set to define the rules of the digital sector for the coming decades. Its success will be a test for regulators, private enforcement, and gatekeepers alike.

*Dr Ann-Christin Richter is a Partner and Dr. Maximilian Volmar is an Associate in the Berlin office.

Footnotes

[1] A. Dryburgh (Forbes), March 22, 2017, Growth Stories: The Magical Power of a Name, https://bit.ly/37leuHq.

[2] OJ L 265, 12.10.2022, p. 1 – 66.

[3] EU Commission, Press release of Nov 30, 2010, Antitrust: Commission probes allegations of antitrust violations by Google.

[4] EU Commission, June 27, 2017, Case AT.39740 – Google Search (Shopping).

[5] EU General Court, Nov 10, 2021, Case T-612/17 – Google and Alphabet v Commission (Google Shopping).

[6] CJEU, Case C-48/22 P (pending) – Google and Alphabet v Commission (Google Shopping).

[7] The term of contestability has a controversial history. Coined by Baumol, Panzar and Willig (Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industry Structure) in 1982, the theory is today thought of by economists as outdated. An updated definition has been put forward by Crémer et al. in 2021 (Fairness and Contestability in the Digital Markets Act, available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3923599).

[8] The DMA is based on Art. 114 TFEU, not Art. 103 TFEU.

[9] A. Satarino (The New York Times), March 24, 2022, E.U. Takes Aim at Big Tech’s Power with Landmark Digital Act, https://nyti.ms/36QrQLI. Experts expect that in particular one of the bills, focused on non-discrimination and inspired by the DMA, has a good chance of being passed in summer 2022.

[10] L. Bertuzzi (Euractiv), March 24, 2022, DMA: EU institutions agree on new rules for Big Tech, https://www.euractiv.com/section/digital/news/dma-eu-institutions-agree-on-new-rules-for-big-tech/.

[11] Andreas Mundt, head of the German Bundeskartellamt, said the DMA is “static” and “precise,” see N. Hirst, N. McNelis, T. Gil (MLex), March 31, 2022, Gatekeepers to see continued EU competition cases despite new platform law, Mundt says, https://content.mlex.com/#/content/1368925?referrer=search_linkclick.

[12] Specifically, gatekeepers shall “refrain from using, in competition with business users, any data not publicly available, which is generated or provided by those business users, in the context of their use of the relevant core platform services or of the services offered together with or in support of the relevant core platform services, including data generated or provided by the end users of those business users.”

[13] EU Commission, Case no. AT.40462 (pending) – Amazon Marketplace.

[14] EU Commission, Press release of April 30, 2021, Antitrust: Commission sends Statement of Objections to Apple on App Store rules for music streaming providers.

[15] Authority for Consumers & Markets, Press release of March 28, 2022, ACM to assess adjusted proposal of Apple regarding its conditions for dating apps, https://www.acm.nl/en/publications/acm-assess-adjusted-proposal-apple-regarding-its-conditions-dating-apps.

[16] Epic Games, Inc. v Apple Inc., Case no. 20-cv-05640-YGR at the US District Court in the Northern District of California, https://cand.uscourts.gov/cases-e-filing/cases-of-interest/epic-games-inc-v-apple-inc/.

[17] A. Cuthbertson (Independent), June 16, 2021, Tim Cook says new European law would ‘destroy’ iPhone security, https://www.independent.co.uk/tech/apple-iphone-privacy-tim-cook-dma-b1867219.html.

[18] Art. 6(1)(b) DMA.

[19] Back then, Microsoft had pre-installed Internet Explorer on Windows, see EU Commission, March 6, 2013, Case no. AT.39530 – Microsoft (Tying).

[20] Recital 46 DMA.

[21] EU Commission, July 18, 2018, Case no. AT.40099 – Google Android; O. Bethell (Google), June 8, 2021, Changes to the Android Choice Screen in Europe, https://blog.google/around-the-globe/google-europe/changes-android-choice-screen-europe/.

[22] EU Commission, June 27, 2017, Case no. AT.39740 – Google Search (Shopping).

[23] EU General Court, Nov 10, 2021, Case no. T-612/17 – Google and Alphabet v Commission (Google Shopping).

[24] CJEU, Case C-48/22 P (pending) – Google and Alphabet v Commission (Google Shopping).

[25] Gatekeepers shall “refrain from treating more favourably in ranking, and related indexing and crawling, services and products offered by the gatekeeper itself or by any third party belonging to the same undertaking compared to similar services or products of third party and apply transparent, fair and non-discriminatory conditions to such ranking.”

[26] Securities and Exchange Commission, Alphabet Inc. 10-K filing 2021, p. 10, available at https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1652044/000165204422000019/goog-20211231.htm#i0ef93c820da04204a9c5a49f49a3b2eb_130.

[27] CMA, Online Platforms and digital advertising, Market study final report, July 1, 2020, para. 5.213.

[28] EU Commission, press release of 22 June 2021, Antitrust: Commission opens investigation into possible anticompetitive conduct by Google in the online advertising technology sector.

[29] Texas et al. v Google LLC, US District Court, S.D.N.Y., Civil Action No.: 1:21-md-03010-PKC, Third amended complaint, para. 5.

[30] CMA, Online Platforms and digital advertising, Market study final report, July 1, 2020, Appendix R: fees in the ad tech stack.

[31] Texas et al. v Google LLC, US District Court, S.D.N.Y., Civil Action No.: 1:21-md-03010-PKC, Third amended complaint, para. 69.

[32] CMA, Online Platforms and digital advertising, Market study final report, July 1, 2020, Appendix O: measurement issues in digital advertising.

[33] J. Furman, D. Coyle, A. Fletcher, D. McAuley, Unlocking digital competition, Report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel, March 2019, p. 12

[34] M. Bourreau, A. de Streel, February 2020, Big Tech Acquisitions: Competition & Innovation Effects and EU Merger Control, https://bit.ly/3wbdwG1.

[35] Art. 22 EU Merger Regulation, Regulation (EC) No. 139/2004.

[36] E. Smith (The Economist), January 20, 2018, The techlash against Amazon, Facebook and Google—and what they can do, https://www.economist.com/briefing/2018/01/20/the-techlash-against-amazon-facebook-and-google-and-what-they-can-do.

[37] Margrethe Vestager, speech at the European Internet Forum, 17 March 2021, Competition in a digital age.

[38] Joint statement by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, the French Ministère de l’économie, des finances et de la relance, and the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy, Strengthening the Digital Markets Act and its Enforcement, https://bit.ly/3whHb0e, p. 1.

[39] Art. 25 DMA.

[40] Competition cases at the EU General Court take around 3-4 years to complete; appeals at the CJEU take around 1-2 years. See Court of Justice of the European Union, Annual Report 2020, Judicial Activity, p. 220, 356, https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/jcms/Jo2_7000/en/.

[41] EU Commission, Oct 16, 2019, Case AT.40608 – Broadcom. The Commission imposed interim measures in other cases before, such as: Commission, press release of May 16, 1995, Irish ferries access to the port of Roscoff in Brittany: Commission decides interim measures against the Morlaix chamber of commerce, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_95_492; Commission, July 29, 1983, Case IV/30.698 – ECS/AKZO. Also see CJEU, Jan 17, 1980, Case 792/79 R – Camera Care. However, the last time that the Commission attempted to impose interim measures before Broadcom was in IMS Health in 2001, a decision which the Commission rescinded during the appeals proceeding: Commission, July 3, 2001, Case COMP D3/38.044 – NDC Health v IMS Health; EU General Court, March 10, 2005, Case T-184/01, para. 53 – IMS Health v Commission.

[42] Art. 278 TFEU.

[43] Act Against Restraints of Competition (Gesetz gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen, GWB).

[44] CJEU, July 15, 1964, Case no. 6/64 – Costa v E.N.E.L.

[45] CJEU, March 22, 2022, Case no. C-117/20 – bpost.

[46] Thomas Kramler, Head of Unit at the EU Commission, in a panel discussion at the D-A-CH Kartellrechtsforum in Göttingen, Germany, 29 April 2022.

[47] Art. 288(2) TFEU.

[48] Art. 31c DMA.

[49] Art. 37d, 37f DMA; Directive 2020/1828 on representative actions for the protection of the collective interests of consumers, OJ (EU) of 4 Dec 2020, No. L 409/1.