Virtual rent-to-own agreements: A fintech disruption

In recent months, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has quietly withdrawn two related enforcement actions pending in federal court.[1] Together, these now-dismissed cases sought to curb a rising, inventive, and controversial financial product: the virtual rent-to-own agreement.

A virtual rent-to-own agreement, or “VirTO,” is a type of sales contract, through which a financial technology company can rent high-cost goods to consumers as an alternative to traditional financing. Critics claim that these agreements represent a predatory form of regulatory arbitrage, allowing businesses to evade consumer protection laws and charge the equivalent of illegally high interest rates.[2] Proponents, in contrast, tout the flexibility of these agreements and their ability to offer a form of credit to subprime and underbanked consumers.[3]

VirTOs are among the latest examples of financial technology companies, or “fintechs,” disrupting ever-deeper corners of the financial services sector to digitize the U.S. economy. These agreements place a new, technology- and AI-driven twist on the classic rent-to-own model of the last 60 years. By dismissing legal challenges with the potential to head off the spread of this new product, the federal government has signaled a newfound tolerance, or perhaps even approval, of the rent-to-own industry’s competitive shift.

This article begins with the basics of the rent-to-own model. It then describes the entry of fintechs into the competitive landscape and the subsequent rise of VirTOs. Lastly, the article considers what may lay ahead for this industry as consumers, competitors, and regulators react.[4]

I. The "Classic" Rent-to-Own Agreement

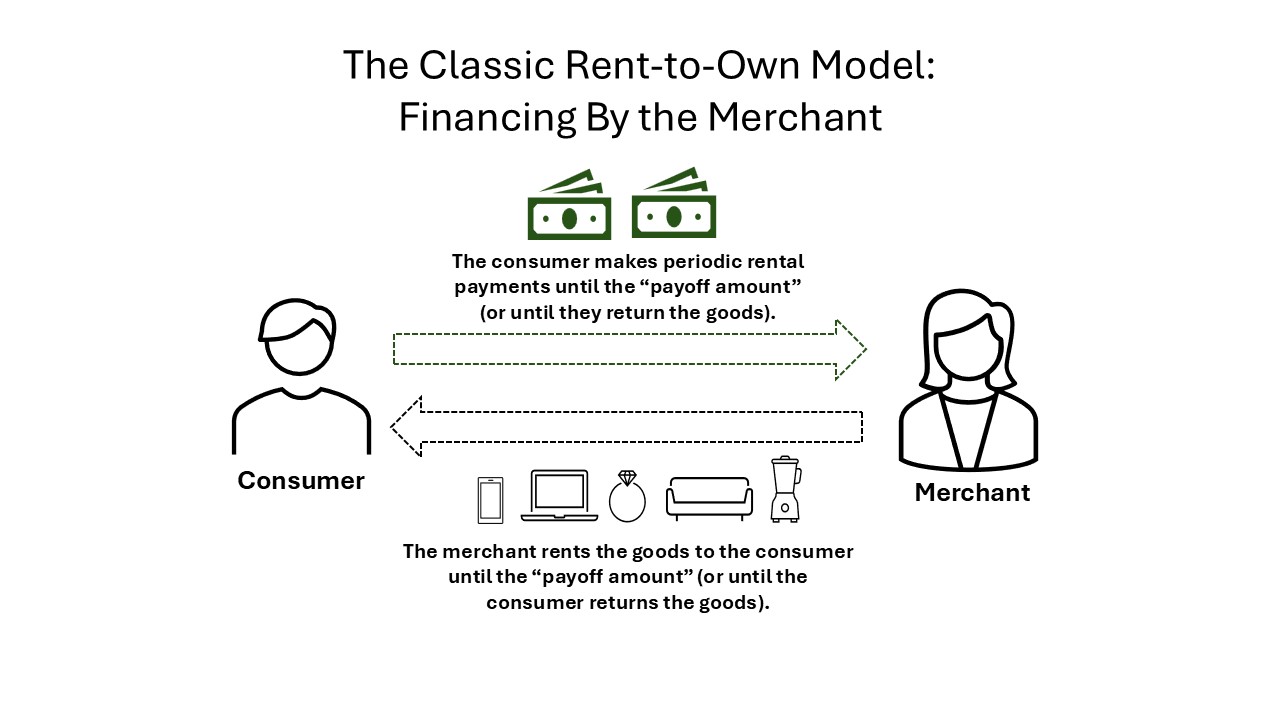

A traditional rent-to-own agreement is a sales contract between a merchant and consumer, by which the merchant rents its goods to the consumer with the intent of eventually transferring ownership to them.[5] It is commonly used as an alternative form of financing for those who cannot pay the full retail costs upfront. Since the 1960s, the traditional rent-to-own model has taken the form of brick-and-mortar retailers, renting big-ticket household items—such as furniture, appliances, and jewelry—to cash-strapped consumers lacking access to traditional forms of credit.[6] These rent-to-own facilities are typically found in low-income neighborhoods.

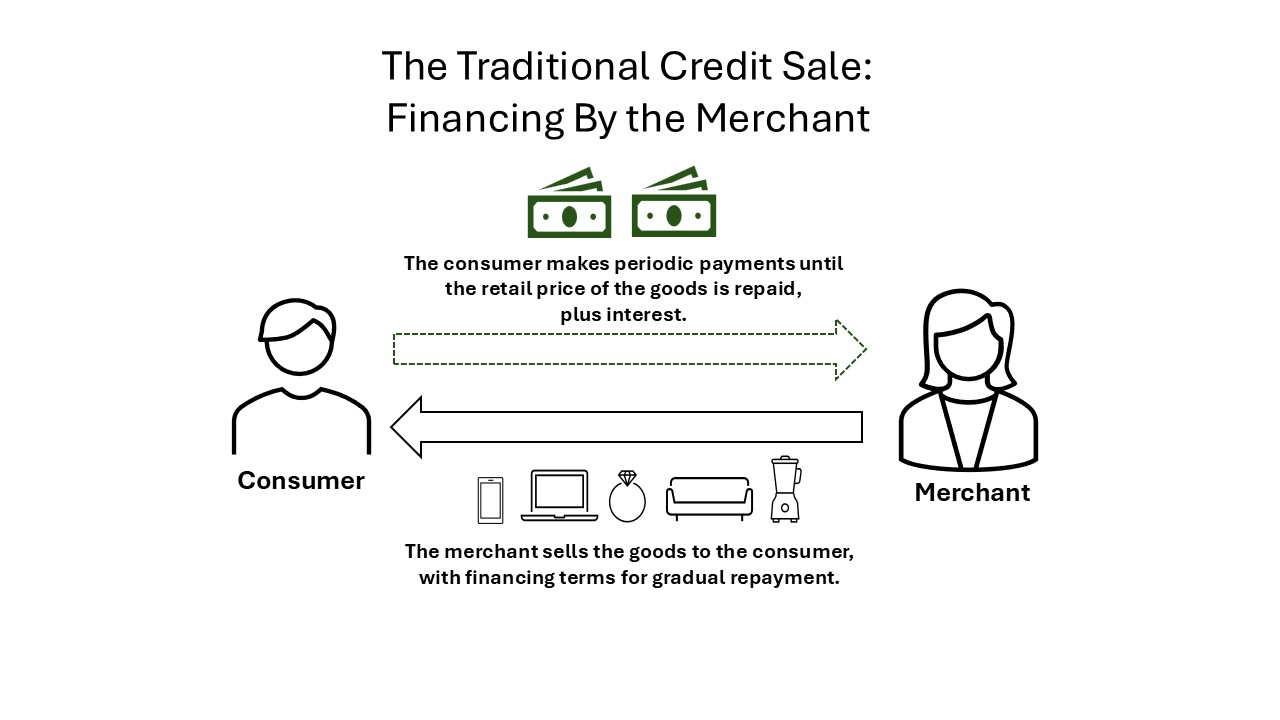

This rent-to-own model looks like a traditional credit sale in practice. The consumer purchases the goods with little or no money down, and in exchange, they make regular payments to the merchant over time, ultimately repaying more than the original retail price of those goods (i.e., repayment with interest).

But in form, the rent-to-own agreement offers merchants a unique benefit that a credit sale does not: by technically “renting” goods to consumers, as opposed to offering the goods on “credit,” rent-to-own agreements can evade a suite of federal consumer protection laws, such as the Truth in Lending Act and Fair Credit Reporting Act, as well as related state laws and usury limits. Indeed, it was the birth of these federal and state laws during the consumers’ rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s that spurred the invention of rent-to-own agreements in the first place.[7]

To be sure, rent-to-own agreements capitalize on a regulatory loophole. But proponents of these agreements have long claimed that consumers, too, receive benefits from these agreements that sales on credit cannot offer. Consumers may want to temporarily rent certain goods, for instance, as opposed to buying them, or they may want to test certain goods before committing to a purchase. And, of course, the rent-to-own model does provide a form of financing for consumers who may lack access to other forms of credit. Without rent-to-own agreements, these consumers may have little recourse when faced with sudden large costs, like, say, replacing a broken water heater or refrigerator.[8]

On the other hand, critics of the rent-to-own model point to its lack of regulation as an inherent, fundamental problem. Because these agreements are not subject to state usury limits or other credit-regulating statutes, limits on the rates rent-to-own merchants may charge are constrained only by their customers’ willingness or ability to pay. As a result, rent-to-own agreements often require consumers to pay several times the original retail price of the goods over the life of the rental agreement, well above the comparable interest rates that many states permit for credit sales.[9] Even the Federal Trade Commission’s website currently warns about the high cost of rent-to-own agreements:

Stores that offer rent-to-own or lease-to-own plans often promote what they think are benefits: choice of different repayment periods, no credit check, automatic withdrawals, and fast approval. But that convenience — for example, getting to use a washing machine while you’re paying it off — can mean you pay twice what you’d pay in cash.[10]

And paradoxically, despite the high total costs of these agreements, the consumers who most often enter into them can least afford them but do so because they lack market alternatives.[11] According to the Association of Progressive Rental Organizations, the national trade association for the rent-to-own industry, the average rent-to-own customer in 2019 had a subprime credit score and an annual income below $36,000.[12]

II. Enter the VirTo: The Virtual Rent-to-Own Agreement

Since the mid-2010s, fintechs have entered and disrupted nearly every sub-section of the financial services sector. From electronic banking and digital wallets, to cryptocurrencies and insurance services, “the key aspect of fintech is a platform that replaces or enhances ‘traditional’ banking and credit services.”[13] The rent-to-own industry has been no exception. Fintech-backed VirTO transactions began to appear around 2015 and quickly “flipped the long-existing, multibillion-dollar RTO industry on its head.”[14] By 2023, the U.S. rent-to-own market was valued in total at more than $12 billion, with billions of dollars in “major investments” continuing to pour into fintechs focused on VirTOs.[15]

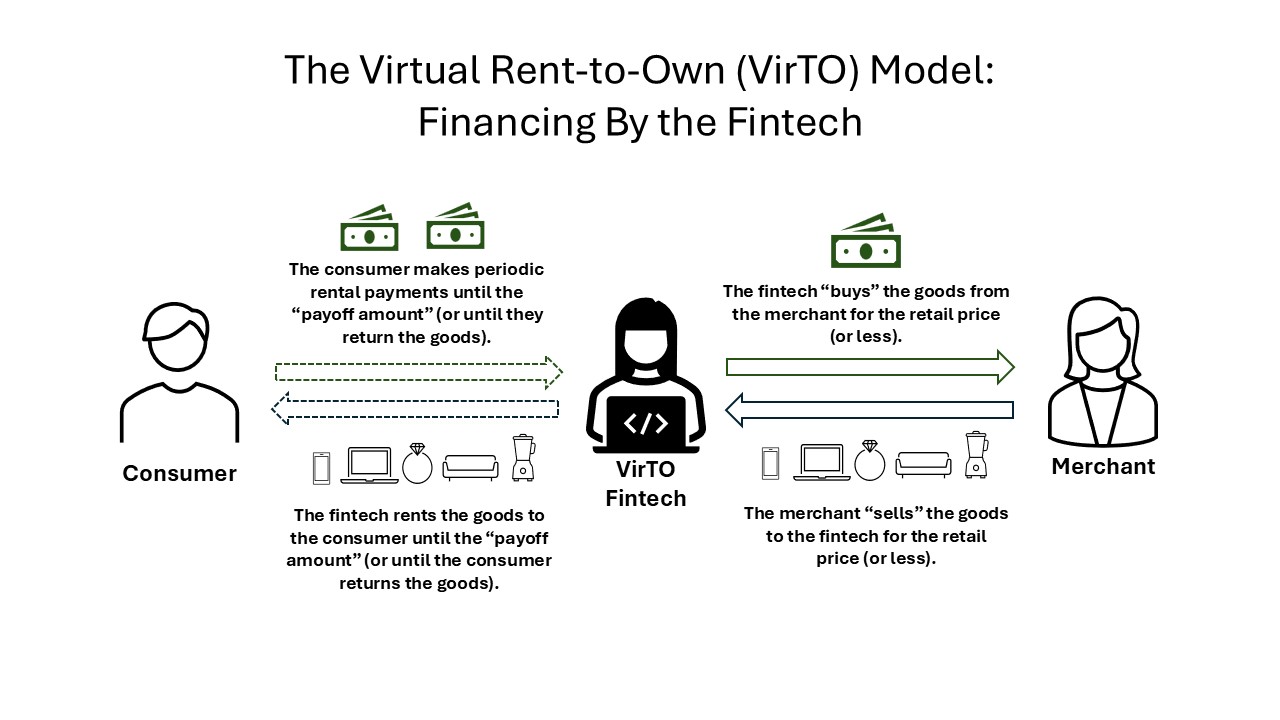

Historically, large brick-and-mortar retail chains like Rent-A-Center and Aaron’s have dominated the rent-to-own industry by renting products directly out of their stores.[16] Notably, these retailers deal in the goods that they rent—they rent appliances and furniture, for example, because they regularly stock and sell those goods already.

VirTO fintechs, in contrast, rent goods to consumers without actually dealing in those goods, or indeed, in any goods. The fintechs partner with brick-and-mortar and digital merchants to act as a third-party financier. When the consumer arrives to the checkout counter of the partnering merchant’s store, or to the checkout page of the digital merchant’s website, the consumer is given the option to “finance” their purchase through the fintech’s VirTO. If the consumer agrees, the fintech buys the goods from the merchant and simultaneously rents them to the consumer, like an invisible middleman, without ever having seen, handled, or physically dealt in the goods themselves. Other than accepting the terms of service—which might be presented through an email to the consumer or on a tablet displayed in the store—and providing their bank account information, the VirTO consumer typically has no interaction with the fintech until the transaction is completed and a contract is formed.

Through this instantaneous process of buying and renting—increasingly aided by artificial intelligence to assess a consumer’s ability to repay and set pricing—fintechs can use VirTOs to rent nearly anything that a consumer might want to finance from a partnering merchant: real estate and housing, car tires, medical equipment, musical instruments, and even products for which “renting” seems infeasible, like auto repair services and pets.[17]

Unsurprisingly, from their first appearance in the mid-2010s, VirTOs have drawn significant attention from competitor brick-and-mortar retailers, whose business model is threatened by the VirTO format. But rather than fight the VirTO tend, the largest traditional rent-to-own retailers have either merged with VirTO fintechs, or have adapted to offer VirTOs themselves through digital storefronts.[18] These competitive choices may have been influenced by a 2020 antitrust settlement between the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) and major rent-to-own operators Aaron’s, Rent-A-Center, and Buddy’s, for allegedly anticompetitive agreements that began in 2015.[19]

Because these traditional rent-to-own industry participants have joined the VirTO wave rather than resist it, and because many of these industry participants had already adapted to earlier e-commerce trends, it is difficult to assess the market share that VirTOs have taken from the brick-and-mortar rent-to-own industry. Credit card companies, too, have in some cases joined forces with VirTO fintechs rather than compete against them. In 2022, for example, Mastercard announced a partnership and specialized credit card with fintech Acima—which was acquired by Rent-A-Center the previous year.[20]

III. VirTO Backlash and What Lies Ahead

In addition to the attention from consumers and competitors, VirTO fintechs have caught the scrutiny of both state and federal regulators. In 2020, the FTC reached a $175 million settlement with VirTO fintech Progressive Leasing for allegedly misleading advertising about pricing. Then, in 2023, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (“CFPB”) brought a first-of-its-kind enforcement action against SNAP Finance, a large VirTO fintech, alleging that SNAP’s terms did not reflect a rent-to-own agreement but rather a “credit sale” to the consumer. If it were successful, such a claim could have dramatically upended the VirTO industry, bringing it under substantially more regulatory control. However, in August of 2024, District Judge Jill N. Parrish rejected the CFPB’s main claim, opining that, whatever the “economic realities” of VirTO agreements, they nonetheless fall outside the federal statutory definition of lending “credit.”[21]

After Judge Parrish’s ruling, the CFPB continued to litigate additional claims against SNAP Finance. And just days before Judge Parrish’s ruling, the CFPB filed a second VirTO complaint against fintech Acima.[22] But following the change in administration, the CFPB voluntarily dismissed both of its actions, marking an abrupt end to the federal government’s years-long effort to regulate VirTOs through enforcement actions.

In the coming years, with the federal government stepping away from its prior scrutiny of VirTOs, state regulators can, and likely will, fill the void. In 2023, the Pennsylvania Attorney General sued SNAP Finance for allegedly misleading advertising to consumers and eventually reached a $11.4 million settlement.[23] A year later, the New York Attorney General filed suit against Acima; that case remains ongoing.

Wherever the future legal challenges to VirTO fintechs come, they are likely to cite a problem that has been baked into the VirTO business model from the start: returning merchandise. Because a traditional rent-to-own consumer is “renting” their goods, as opposed to owning them on credit, the consumer can simply return the goods at any time, and, in theory, they would instantly terminate the agreement. For a traditional brick-and-mortar retailer, that return process may be inconvenient, but it is relatively simple. The retailer can receive the returned goods, add them back to their stock, and hope to rent them again.

But for a VirTO fintech that is not affiliated with a brick-and-mortar rent-to-own facility, consumer returns are much more problematic. VirTO fintechs typically lack the physical capacity to accept returns for the thousands of appliances, furniture items, and other high-dollar goods that they own and rent to consumers across the United States. Car tires, for instance, are among the most common goods that consumers rent through virTOs. If a consumer in North Dakota wishes to terminate their VirTO and return four car tires to the Brooklyn-based fintech who technically owns them, there are of course serious logistical barriers. Beyond these, however, there are also larger issues of fairness to a consumer who no longer wishes to rent but who faces significant hurdles in ceasing to do so. Relatedly, fintechs that offer VirTOs should expect to see challenges related to what Professor Floyd describes as “nonsensical” rent-to-own agreements, such as those for services or pets.[24]

On top of litigation, companies that offer VirTOs may soon see increased regulation at the state level as well. In New York, for example, the Governor’s statewide budget has repeatedly suggested “sweeping” legislation to regulate the buy-now-pay-later industry, which is a close cousin of the rent-to-own industry.[25] And other states like Nevada and California have already banned the leasing of certain goods that lack residual value, such as pets, car tires, batteries, and hearing aids.[26]

Whatever the future holds for virtual rent-to-own agreements, and the financial

technology companies employing them, they are likely here to stay, as both a disruption to the consumer financial services sector, and as yet another step towards a more digitized U.S. economy.

[1] See Notice of Voluntary Dismissal, C.F.P.B. v. Acima Holdings LLC, No. 24-cv-525 (D. Utah Mar. 6, 2025) and Notice of Voluntary Dismissal, C.F.P.B. v. Snap Finance LLC, No. 23-cv-462 (D. Utah May 27, 2025).

[2] See, e.g., Why Rent-to-Own is Bad, Cmty. Legal Servs. of Phila., https://clsphila.org/rent-to-own/why-rent-to-own-is-bad/ (last visited Aug. 26, 2025); Sarah Brady, Why Rent-to-Own is the Wrong Choice for You, Nat’l Found. for Credit Counseling (Feb. 28, 2025), https://www.nfcc.org/blog/why-rent-to-own-is-the-wrong-choice-for-you/; Greg Buchak, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, & Amit Seru, Fintech, Regulatory Arbitrage, and the Rise of Shadow Banks, 130 J. Fin. Econ. 453 (2018) (discussing the drawbacks of shadow banking generally).

[3] See, e.g., Ann O’Connoll, The Basics of Rent-To-Own Agreements, NOLO (June 22, 2023), https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/the-basics-rent-own-agreements.html; Carol Galante, Carolina Reid, Rocio Sanchez-Moyano, Expanding Access to Homeownership through Lease-Purchase, Terner Ctr. for Hous. Innovation (2017), https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/lease-purchase.pdf.

[4] The VirTO moniker was coined by Carrie Floyd, Assistant Professor of Law at the University of North Carolina School of Law. In 2024, Professor Floyd authored the first academic scholarship on virtual rent-to-own agreements: Carrie Floyd, New Tech, Old Problem: The Rise of Virtual Rent-to-Own Agreements, 65 B.C. L. Rev. 763 (2024). Professor Floyd was also a clinical advisor to this article’s author from 2021 to 2022, for which the author is ever grateful.

[5] Rent-to-own agreements (“RTOs”) are also known as “lease purchase agreements” or “lease-to-own agreements,” with merchants referred to as “lessors” and consumers as “lessees.” Rent-to-own agreements are not synonymous, however, with Buy Now Pay Later (“BNPL”) agreements, which do not require consumers to “rent” or “lease” property. See Buy Now, Pay Later, Rent-to-Own, Lease-to-Own, and Layaway, Consumer Advice, Fed. Trade Comm’n, https://consumer.ftc.gov/buy-now-pay-later-rent-own-lease-own-layaway (last visited Aug. 26, 2025).

[6] Rent-to-own agreements are generally considered a form of “fringe banking,” a concept first put forth by John P. Caskey in his 1996 book, “Fringe Banking: Check-Cashing Outlets, Pawnshops, and the Poor.”

[7] See James P. Nehf, Effective Regulation of Rent-to-Own Contracts, 52 Ohio St. L.J.751, 753-57 (1991); see also Matthew A. Edwards, Empirical and Behavioral Critiques of Mandatory Disclosure, 14 Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 199, 206-11 (2005).

[8] Floyd, supra note 2 at 782.

[9] Jim Hawkins, Renting the Good Life, 49 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 2041, 2041 (2008) (explaining that rent-to-own consumers often pay “more than double the purchase price” of goods, with implied APRs greater than 200%).

[10] See Buy Now, Pay Later, Rent-to-Own, Lease-to-Own, and Layaway, Consumer Advice, Fed. Trade Comm’n, https://consumer.ftc.gov/buy-now-pay-later-rent-own-lease-own-layaway (last visited Aug. 26, 2025).

[11] The rent-to-own model can also further damage a subprime consumer’s credit score, because the lessor may require an initial “hard” credit check of the consumers’ score and may subsequently report any missed or delayed rental payments. See Floyd, supra note 2 at 783-84. But see Jim Hawkins, Regulating on the Fringe, 86 Ind. L.J. 1361 (2011) (finding “the link between fringe banking and financial distress” surprisingly “dubious”).

[12] Floyd, supra note 2 at 813 (citing Ass’n of Progressive Rental Orgs., The Rent-to-Own Industry; About RTO at 9 (2019), https://perma.cc/CZU5-A5QT).

[13] Pamela Foohey & Nathalie Martin, Fintech’s Role in Exacerbating or Reducing the Wealth Gap, 2021 U. Ill. L. Rev. 459, 488 (2021).

[14] Floyd, supra note 2 at 768.

[15] Sarah Hansen, Rent-to-Own Homes Are Back With a Fintech Facelift, but Can They Escape Their Sketchy Past?, Money (Apr. 14, 2022), https://money.com/rent-to-own-homes/; see also US Rent-To-Own Market Thrives: Distribution Channels, Sizing & Impact Forecast Through 2029, Bus. Wire (Feb. 12, 2024), https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20240212310817/en/US-Rent-To-Own-Market-Thrives-Distribution-Channels-Sizing-Impact-Forecast-Through-2029---ResearchAndMarkets.com.

[16] Floyd, supra note 2 at 789.

[17] Id. at 798 n.202.

[18] See, e.g., Rent-A-Center Closes Acquisition of Acima Holdings, Bus. Wire (Feb. 17, 2021), https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210217005593/en/Rent-A-Center-Closes-Acquisition-of-Acima-Holdings; IQVentures Completes Acquisition of The Aaron's Company, PR Newswire (Oct. 3, 2024), https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/iqventures-completes-acquisition-of-the-aarons-company-302267226.html

[19] Press Release, Rent-to-Own Operators Settle Charges that They Restrained Competition through Reciprocal Purchase Agreements, Fed. Trade Comm’n (Feb. 21, 2020), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2020/02/rent-own-operators-settle-charges-they-restrained-competition-through-reciprocal-purchase-agreements.

[20] Elizabeth Gravier, Cash-Strapped and Credit-Constrained Consumers: Here’s a New Way to Pay for (and Own) Things, CNBC (Sept. 9, 2022), https://www.cnbc.com/select/acima-leasepay-card-announced/.

[21] See Memo. Decision & Order at 13-15 & n.12, C.F.P.B. v. Snap Finance LLC, No. 23-cv-462 (D. Utah Aug. 1, 2024).

[22] Compl., C.F.P.B. v. Acima Holdings LLC, No. 24-cv-00525 (D. Utah July 26, 2024).

[23] Pa. Reaches $11 Million Settlement with 'Predatory' Rent-to-Own Lender, CBS Pitt. (May 15, 2023), https://www.cbsnews.com/pittsburgh/news/pennsylvania-settlement-predatory-rent-to-own-lender-restitution-debt-relief/.

[24] Floyd, supra note 2 at 798-800.

[25] See, e.g., John A. Kimble, New York Governor’s Proposed TED Bill Includes Sweeping BNPL Legislation, Consumer Fin. Monitor, Ballad Spahr LLP (Jan. 24, 2024) https://www.consumerfinancemonitor.com/2024/01/25/new-york-governors-proposed-ted-bill-includes-sweeping-bnpl-legislation/.

[26] See Floyd, supra note 2 at 825-26.