Government pesticides loyalty discount suit withstands dismissal motion

A lawsuit filed by the FTC and a dozen states alleges that two major pesticide manufacturers, Syngenta and Corteva,[1] used loyalty programs to incentivize purchases of their branded crop-protection products in violation of various federal and state competition laws. According to the complaint, each company produced three branded crop protection products with distinct active ingredients, commanding dominant market shares for each respective branded product. The complaint further alleged that the loyalty programs orchestrated by each defendant effectively constituted de facto exclusive dealing arrangements aimed at preserving the dominant market share of each of the six products, in violation of Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act, Section 3 of the Clayton Act, Section 5 of the FTC Act, and various state competition laws.[2]

The defendants filed a motion to dismiss contending, among other issues, that the plaintiffs had failed to identify an appropriate relevant product market and had not alleged actionable anticompetitive conduct and marketplace harm under the applicable statutes. The defendants stressed that while a district court should “accept as true all of the factual allegations contained in the complaint” at the motion to dismiss stage,[3] a plaintiff must allege “more than labels and conclusions, and a formulaic recitation of the elements of a cause of action;” the complaint must contain sufficient factual matter to “state a claim to relief that is plausible on its face.”[4]

The court denied defendants’ motion to dismiss, ruling that the plaintiffs had plausibly alleged violations of each cause of action identified in the complaint.[5] As discussed below, the court denied defendants’ primary arguments in their motion to dismiss, ruling that plaintiffs had plausibly alleged six relevant product markets consisting of each of the defendants’ branded crop protection products (and its active ingredient), and that plaintiffs had plausibly alleged that defendants engaged in anticompetitive conduct that caused harm to competition in each of the relevant markets.

Background on applicable federal competition laws

Loyalty discounts – sometimes referred to as market share discounts – are agreements between suppliers and their customers designed to encourage the purchase of a specific volume of the supplier’s product in return for a reward, often in the form of a discount or other price reduction.

There is no Supreme Court decision addressing loyalty or market share discounts, and the circuit courts have not ruled consistently with respect to such programs when the defendant has had market or monopoly power but sold the applicable products above cost. In fact, such programs have been found lawful even when adopted by a company with market or monopoly power when customers have been free to walk away and have done so,[6] and/or when competitors have been able to successfully counter such programs with their own.[7] On the other hand, a leading appellate court decision declared that a dominant company’s 5 to 7 year loyalty agreements with major buyers constituted unlawful de facto exclusive dealing arrangements when a substantial share of the market was foreclosed to the defendant’s principal competitor.[8]

Exclusive dealing arrangements may be impermissible under any of the federal competition laws: the Sherman Act, Clayton Act, and FTC Act. Section 1 of the Sherman Act bans “[e]very contract, combination . . . or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States.”[9] Section 2 makes it illegal to “monopolize, or attempt to monopolize . . . any part of the trade or commerce among the several States.”[10] Section 3 of the Clayton Act addresses tying and exclusive dealing arrangements by prohibiting firms from offering a “price” or “rebate” “on the condition, agreement, or understanding that the . . . [buyer] shall not use or deal in the goods . . . of a competitor or competitors . . . where the effect . . . may be to substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly in any line of commerce.”[11]

While Sherman Act exclusive dealing violations require actual anticompetitive harm, Section 3 of the Clayton Act proscribes such conduct for exclusive arrangements “where the effect . . . may be to substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly in any line of commerce.”[12] Accordingly, unlike the Sherman Act, the Clayton Act prohibits an exclusive dealing arrangement that only has the probable effect of substantially lessening competition.[13] As the Clayton Act’s coverage is broader than the Sherman Act’s application, “if it does not fall within the broader proscription of § 3 of the Clayton Act, it follows that it is not forbidden by those of the [Sherman Act].”[14]

And, finally, practices that violate the Sherman and Clayton Act also violate Section 5 of the FTC Act. In fact, the FTC Act is broader in that it proscribes unfair methods and practices that do not actually violate but run “counter to the public policy declared in the [Sherman] Act.”[15]

Factual background of lawsuit against Syngenta and Corteva

Syngenta and Corteva manufacture a range of crop-protection products. Each product contains at least one active ingredient encompassing characteristics based on several factors, including which pests to target and how the pests are targeted and neutralized. Purchasers of crop-protection products may prefer one active ingredient over another based on its unique characteristics, including the mode in which it handles a specific pest problem.[16]

Ninety percent of crop protection products follow through a “traditional” supply chain pursuant to which manufacturers sell products to distributors, distributors then sell the products to retailers, and retailers then sell the products to end users—mainly farmers. Significantly, there are seven distributors that account for 80% of the sales of crop-protection products in the United States. Access to distribution is a key factor in enabling generic manufacturers to compete against the defendants.[17]

Developers of crop protection products use two avenues to obtain exclusive use of their product. First, the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (“FIFRA”) provides the means for a developer to obtain a 10-year exclusive protection.[18] Second, for patented products, patent laws allow the developer to obtain 20 years of patent protection for their product.[19] When these exclusive-use periods expire, manufacturers of generics may develop the crop protection products and begin selling them to distributors and others in competition with the defendants’ brands.

Syngenta and Corteva offer loyalty programs to induce distributors to continue purchasing products from them after the exclusive-use period for their products have ended. According to the complaint, defendants’ loyalty programs were designed to be “all-or-nothing” type agreements: if a distributor did not meet the loyalty threshold for a particular product, it risked losing the entirety of the lump sum payment related to that particular product. Furthermore, according to the complaint, distributors also risked retaliation by the defendants, either in the form of having their distribution contracts cancelled or losing access to supply.[20]

The loyalty programs at issue

Syngenta’s loyalty program, known as “KeyAI,” offered a distributor a substantial end-of-year lump sum payment if it sourced anywhere between 85% to 99% of the specified product from Syngenta.[21] For example, according to the complaint, Syngenta once set a requirement that a distributor had to purchase 99% of one of its three applicable products, mesotrione, from Syngenta to qualify for its loyalty payment.[22] In other words, no more than 1% of a distributor’s purchases of mesotrione could come from a generic manufacturer. A distributor that failed to purchase the required share of a product from Syngenta, according to plaintiffs, risked retaliation by losing their loyalty payments, having their distribution contracts cancelled, or having supplies withheld.[23]

Corteva’s program is known as the Crops, Range & Pasture and Industrial Vegetation Management program (“CRPIVM”) and, like Syngenta’s loyalty program, provides an annual lump-sum payment to a distributor if it sourced anywhere from 85% or more of the applicable product from Corteva. This payment could be as high as 11% of the purchases made by the distributor.[24] Furthermore, according to the complaint, Corteva’s CRPIVM program also linked to other offers it provided to distributors, and distributors could forfeit such other offers if they failed to meet the CRPIVM figures. Like Syngenta’s program, according to plaintiffs, distributors that failed to purchase the required share of a product from Corteva risked retaliation by losing their loyalty payments, having their distribution contracts cancelled, or having supplies withheld.[25]

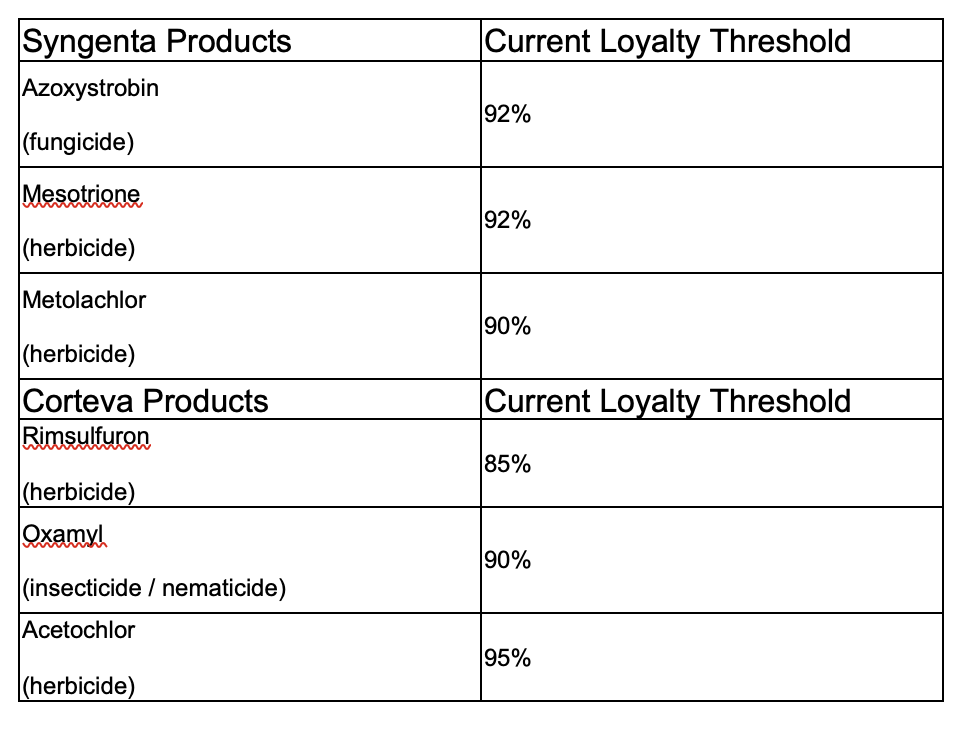

The six products at issue are listed below along with the alleged purchase threshold necessary for a distributor to qualify for the applicable loyalty program:

According to the complaint, generic manufacturers of the above-referenced branded products were either dissuaded from entering the market or had to exit the market.[26] Even though farmers sometimes demanded lower-priced generics, and even though some generic manufacturers priced their products “substantially below” the prices of defendants’ branded products, generic manufacturers made “little headway” because distributors declined to purchase the generic product as a result of defendants’ loyalty programs.[27] The complaint alleged that one of defendants’ employees remarked that their “team truly has done an A+ job blocking generics.”[28]

While defendants advanced several arguments, the two principal arguments concerned whether plaintiffs had plausibly alleged appropriate relevant product markets and had plausibly alleged anticompetitive conduct and marketplace harm. As summarized below, the court did not dismiss any of plaintiffs’ claims.

Relevant product market

Corteva and Syngenta contested the propriety of the plaintiffs’ two alleged product markets: 1) each relevant active ingredient itself; and 2) each finished pesticide product. The plaintiffs referred to each of the six discrete active ingredients developed by Syngenta and Corteva noted above: Azoxystrobin, Mesotrione, Metolachlor, (together, the “Syngenta Products”) and Rimsulfuron, Oxamyl, and Acetochlor (together, the “Corteva Products”).

Courts have at their disposal various methods of determining the relevant product market in a rule of reason case, such as this one. One method, which was applied by the district court, is by using the so-called Brown Shoe factors: “industry or public recognition of the market as a separate economic entity, the product’s peculiar characteristics and uses, unique production facilities, distinct customers, distinct prices, sensitivity to price changes, and specialized vendors.”[29]

Applying the Brown Shoe factors, the district court agreed with plaintiffs that, for purposes of the motion to dismiss, the complaint had plausibly alleged that each Syngenta Product and Corteva Product constituted its own single-product market, similar to cases involving pharmaceutical products where courts have found a plausible product market consisting of a branded drug and its generic alternative.[30] According to the court, defendants’ own conduct suggested that each of them treated each of their products as its own product market. For example, each loyalty program covered only an individual Corteva Product or Syngenta Product, rather than all active ingredients or a segment of active ingredients. Second, the court ruled it plausible for purposes of a motion to dismiss that the entry of a competitive product with the same generic active ingredient would lead to lower prices of the branded Syngenta Product or Corteva Product, suggesting that there were no current substitutable products competing with the defendants’ branded products.[31] Finally, the court agreed that plaintiffs had plausibly alleged that each of the three Syngenta Products and the three Corteva Products had unique characteristics, that farmers did not consider alternatives to defendants’ branded products as suitable substitutes, and that farmers had a preference for each of defendant’s branded products.[32]

Finally, the court reiterated the usual determination that the relevant product market issue is a “question of fact,” and that defendants would be able to contest the relevant market again “after the facts develop.”[33]

Anticompetitive conduct and harm

The major competition issue that the parties contested was whether the complaint had adequately alleged an impermissible exclusive dealing claim. Even though less than 100% of the market was alleged to have been foreclosed by defendants’ loyalty programs, de facto exclusive dealing arrangements that have the effect of preventing distributors from handling the products of a competing supplier, or otherwise foreclose a substantial share of the market, have given rise to antitrust liability under both the Clayton Act and Sherman Act.[34] It was stated in the D.C. Circuit's Microsoft decision that a plaintiff alleging an impermissible exclusive dealing arrangement under Section 1 of the Sherman Act must demonstrate foreclosure of a substantial share of the relevant market,[35] usually at least “40% or 50%” foreclosure.”[36] Less is required in a monopolization case under Section 2.[37] As previously noted, under Section 3 of the Clayton Act, plaintiffs need only allege a “probable” effect of “foreclos[ure of] competition in a substantial share of the line of commerce affected.” [38]

As noted above, exclusive dealing claims are subject to a rule of reason analysis.[39] The Supreme Court discussed the following considerations in analyzing an exclusive dealing arrangement under the rule of reason rubric:

[T]he probable effect of the contract on the relevant area of effective competition, taking into account the relative strength of the parties, the proportionate volume of commerce involved in relation to the total volume of commerce in the relevant market area, and the probable immediate and future effects which pre-emption of that share of the market might have on effective competition therein.[40]

The court ruled that the complaint sufficiently alleged both direct and indirect harm to competition.[41]

Specifically, the court pointed out that the plaintiffs had alleged foreclosure of well above 40%-50% of the relevant market: here, Syngenta and Corteva had foreclosed generic competitors from approximately 70% or more of the applicable market for each Syngenta Product and Corteva Product.[42]

Additionally, according to the complaint, the loyalty programs effectively limited the participation of generics from the marketplace.[43] As summarized above, 90% of crop protection products are sold through the traditional supply chain: manufacturers sell to distributors, who then sell to retailers, who then sell to farmers. The loyalty programs effectively ensured that the seven large distributors only purchased and promoted the branded Syngenta Products and Corteva Products, rather than the generics.

Specifically, according to plaintiffs, distributors limited their purchase, promotion, and sale of any generic competitors by, for example: omitting generic products from their price lists, refusing customer requests for generics, declining generic companies’ offer to supply, and otherwise steering retailers toward defendants’ products rather than generics.[44] As a result, according to the complaint, there was no meaningful ability for generic manufacturers to compete, and no ability to source any alternative avenues for the products.[45]

Finally, and as noted above, Syngenta and Corteva allegedly had threatened retaliation against distributors that did not purchase the threshold amounts for each product at issue. If purchasers did not meet the market share threshold for any Syngenta Product or Corteva Product, the defendants threatened to withhold or reverse the lump-sum payment awards, threatened to limit supply and access to the applicable crop protection product, or even threatened to cancel distribution contracts with the distributors.[46] According to the allegations, distributors could not risk jeopardizing their relationship with the largest manufacturers of crop-protection products and potentially lose access to all supply of defendants’ products.[47]

Price cost test not applicable

Defendants argued in their motion to dismiss that the plaintiffs’ claims should have been evaluated under the so-called price-cost test.[48] That test is applied in predatory pricing cases but, according to the Supreme Court’s Brooke Group decision, to be successful, a plaintiff must demonstrate both (1) “that the prices complained of are below an appropriate measure of [the defendant’s] costs;” and (2) that the defendant had “a dangerous probability of recouping its investment in below-cost prices.”[49]

The defendants’ motion to dismiss attempted to cast plaintiffs’ claims so as to have the court apply the “price-cost” test.[50] The court ruled, however, that the price-cost test does not apply where, as here, the plaintiffs alleged non-price mechanisms of exclusion to ensure that distributors did not purchase generics, resulting in the functional elimination of competition from generic manufacturers.[51] In any event, the plaintiffs had not alleged that defendants engaged in predatory pricing or otherwise priced their products below cost.[52]

It is significant that the Supreme Court has been very skeptical about punishing above-cost price cuts. It has continually stressed that low prices hardly pose antitrust concerns if there is little likelihood of recoupment, and if not below cost are procompetitive.[53] One Third Circuit decision in fact called into question the continued vitality of the price-cost test to loyalty or market share discounts, declining to decide “when, if ever, the price-cost test applies to this type of claim.”[54]

Conclusion

Although the government’s pesticides loyalty discount case escaped a motion to dismiss, other plaintiffs alleging anticompetitive loyalty discount or market share programs have had mixed success. Courts have not taken issue with such programs when customers have a meaningful choice to purchase from competitors.[55] For example, one circuit court stressed that there was no violation because buyers “were free to walk away from the discounts at any time and they in fact switched ... when [a competitor] offered superior discounts.”[56]

On the other hand, courts have taken issue with loyalty discount agreements by companies with market or monopoly power when such arrangements have included non-price factors, or factors that otherwise limit or preclude competition.[57] Accordingly, what will happen next in the government’s pesticides loyalty case will be of considerable interest.

*S. Farhad Mirzadeh is an Associate in Washington, D.C. and Irving Scher is a former Chair of both ABA and NY State Bar Association Antitrust Sections, and is retired from the practice of law.

Footnotes

[1] The named defendants include: Syngenta Crop Protection AG, Syngenta Corporation, Syngenta Crop Protection, LLC (collectively “Syngenta”), and Corteva, Inc (“Corteva”). The plaintiffs include the Federal Trade Commission and the states of California, Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin.

[2] This article focuses on the court’s discussion of the federal antitrust laws. The defendants also moved to dismiss claims based on various state antitrust and consumer protection statutes, which generally follow the federal standards, as well as other constitutional and procedural arguments, all of which were also denied at the motion to dismiss stage.

[3] Erickson v. Pardus, 551 U.S. 89, 94 (2007) (per curiam) (citing Bell Atl. Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 555-56 (2007)).

[4] Twombly, 550 U.S. at 555, 570.

[5] Mem. Op. & Order 2-5, FTC v. Syngenta Crop Protection AG et al., No. 1:22-cv-00828-TDS-JEP, (M.D.N.C. Jan. 12. 2022), ECF No. 160 (“Op.”), (“FTC v. Syngenta”).

[6] See, e.g., Esai, Inc. v. Sanofi Aventis, U.S., LLC, 821 F.3d 394 (3d Cir. 2016); Concord Boat Co. v. Brunswick Corp., 207 F.3d 1039 (8th Cir. 2000).

[7] See, e.g., FTC v. Qualcomm Inc., 969 F.3d 974 (9th Cir. 2020); Virgin Atlantic Airways Ltd. v. British Airways, PLC, 257 F.3d 256 (2d Cir. 2001).

[8] ZF Meritor, LLC v. Eaton Corp., 696 F.3d 254 (3d Cir. 2012), cert. denied, 133 S. Ct. 2025 (2013).

[9] 15 U.S.C. § 1.

[10] 15 U.S.C. § 2.

[11] 15 U.S.C. § 14.

[12] Id.

[13] See, e.g., Tampa Elec. Co. v. Nashville Coal Co., 365 U.S. 320, 329-330 (1961); Am. Motor Inns, Inc. v. Holiday Inns, Inc., 521 F.2d 1230, 1250-51 (3d Cir. 1975).

[14] Tampa Elec. Co., 365 US at 335.

[15] Atl. Refining Co. v. FTC, 381 U.S. 357, 369-70 (1965); Fashion Originators' Guild of Am. v. FTC, 312 U.S. 457, 463-64 (1941).

[16] Mem. Op. & Order 2-5, FTC v. Syngenta Crop Protection AG et al., No. 1:22-cv-00828-TDS-JEP, (M.D.N.C. Jan. 12. 2022), ECF No. 160 (“Op.”), (“FTC v. Syngenta”).

[17] See Op. at 4-5.

[18] Op. at 4.

[19] Id.

[20] Op. at 47.

[21] Pls.’ Mem. In Opp. To Defs.’ Mots. to Dismiss at 6, FTC v. Syngenta (Feb. 10, 2023), ECF No. 110.

[22] Id.

[23] Op. at 7, 47.

[24] Op. at 6-8.

[25] Id. at 6-7.

[26] Id. at 63-64.

[27] Id. at 64.

[28] Id.

[29] Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 325 (1962).

[30] Op. at 31 (citing In re Nexium (Esomeprazole) Antitrust Litig., 968 F. Supp. 2d 367, 388-399 (D. Mass. 2013); and In re Zetia (Ezetimibe) Antitrust Litig., MDL No. 2:18-md-2836, 2021 WL 6689718, at *19 (E.D. Va. Nov. 1, 2021).

[31] Op. at 31-32.

[32] Op. at 32.

[33] See id. at 25, 32; see also Eastman Kodak Co. v. Image Technical Servs., Inc., 504 U.S. 451, 481-82 (1992).

[34] See, e.g. ZF Meritor, 696 F. 3d at 283-84 (“[A]lthough the market-share targets covered less than 100% of the OEMs' needs, a jury could nevertheless find that the LTAs unlawfully foreclosed competition in a substantial share of the HD transmissions market.”); United States v Dentsply Int’l Inc., 399 F.3d 181, 191 (3d Cir. 2005) (“[T]he test is not total foreclosure, but whether the challenged practices bar a substantial number of rivals or severely restrict the market's ambit.”).

[35] Op. at 36-37 (citing Chuck's Feed & Seed Co., Inc. v. Ralston Purina Co., 810 F.2d 1289, 1293 (4th Cir. 1989)).

[36] United States v. Microsoft Corp., 253 F.3d 34, 70 (D.C. Cir. 2001).

[37] Id.

[38] Tampa Elec., 365 U.S. at 327.

[39] Id. Per se treatment is not appropriate in exclusive dealing cases because courts have acknowledged that such arrangements are capable of increasing welfare by “lead[ing] dealers to promote each manufacturer's brand more vigorously than would be the case under nonexclusive dealing” and “prevent[ing] dealers from taking a free ride” on one manufacturer's promotional efforts. See Roland Mach Co. v. Dresser Indus., 749 F.2d 380, 395 (7th Cir. 1984).

[40] Tampa Elec., 365 U.S. at 329.

[41] Op. at 56-64.

[42] Op. at 56-57.

[43] Id. at 57, 63-64.

[44] Op. at 66.

[45] See, e.g., Op. at 56-57.

[46] See, e.g., Op. at 7, 47.

[47] Op. at 62-63 (quoting ZF Meritor, 696 F.3d at 283 (“no risk averse business would jeopardize its relationship with the largest manufacturer of transmissions in the market” (internal quotation marks omitted)) and Dentsply Int’l Inc., 399 F.3d at 194 (“[I]n spite of the legal ease with which the relationship can be terminated, the dealers have a strong economic incentive to continue” their relationship with defendants).

[48] Op. at 34 (quoting Cargill Inc. v. Montfort of Colorado, Inc., 479 U.S. 104, 117 (1986)).[49] Brooke Grp. Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 509 U.S. 209, at 222-24 (1994).

[50] See, e.g., Mem. of Law in Support of Syngenta’s Mot. to Dismiss at 14-18, FTC v. Syngenta, ECF No. 78 (M.D.N.C. Dec. 12, 2022).

[51] Op. at 33, 55-56.

[52] Id.

[53] Brooke Grp. Ltd., 509 U.S. at 222-24 (“the exclusionary effect of prices above a relevant measure of cost either reflects the lower cost structure of the alleged predator, and so represents competition on the merits”); Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp., 475 U.S. 574, 594 (1986) (“[C]utting prices in order to increase business often is the very essence of competition. Thus, mistaken inferences in cases such as this one are especially costly, because they chill the very conduct the antitrust laws are designed to protect”); Atlantic Richfield Co. v. USA Petroleum Co., 495 U. S. 328, 340 (1990) (“Low prices benefit consumers regardless of how those prices are set, and, so long as they are above predatory levels, they do not threaten competition . . . . We have adhered to this principle regardless of the type of antitrust claim involved.”).

[54] Eisai, Inc. v. Sanofi Aventis U.S., LLC, 821 F.3d 394, 409 (3d Cir. 2016).

[55] See, e.g., Concord Boat, 207 F.3d at 1045 (the loyalty programs did not obligate boat builders and dealers to purchase engines from Brunswick, and none of the programs restricted the ability of builders and dealers to purchase engines from other engine manufacturers); S.E. Missouri Hosp. v. C.R. Bard, Inc., 642 F.3d 608, 612-13, 616-17 (8th Cir. 2011) (a supplier’s “share-based” discounts did not violate Sections 1 or 2 of the Sherman Act because buyers were not required to purchase from the defendant, were free to purchase from elsewhere (and did so), and the agreements were terminable at will); PepsiCo, Inc. v. Coca-Cola Co., 315 F.3d 101, 102, 104 (2d Cir. 2002) (plaintiff did not demonstrate that defendant’s loyalty discounts gave it the ability to control prices or exclude competition).

[56] Concord Boat Corp., 207 F.3d at 1059.

[57] See, e.g., ZF Meritor, 696 F.3d at 265-66 (loyalty arrangement’s non-price factors, including requirements that the OEMs use catalogs to highlight the defendant’s products and exclude plaintiff’s products, and raising the price of competitor products above the prices charged for the defendant's products constituted de facto exclusive dealing arrangement).