FTC says to ignore its previous guidance about PBMs

The cost of prescription medications in the United States has been steadily on the rise. A recent report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has found that the price of thousands of drugs spiked upwards by over 30% between 2021 and 2022 alone, far outpacing inflation.[1] This affordability crisis is felt no more acutely than by the millions of American consumers who depend on these medications each day.

Pharmaceutical industry players point to different causes for the price hikes: manufacturing and supply shortages, the development of new brand biologics, the rate of inflation, and a general lack of competition in the market for brand-name drugs, leading to year-over-year increases.[2] However, attention is increasingly shifting among industry observers towards the shadowy middlemen in the pharmaceutical industry as a key reason for these prices increases: pharmacy benefit managers (or “PBMs”).

Background: What are PBMs?

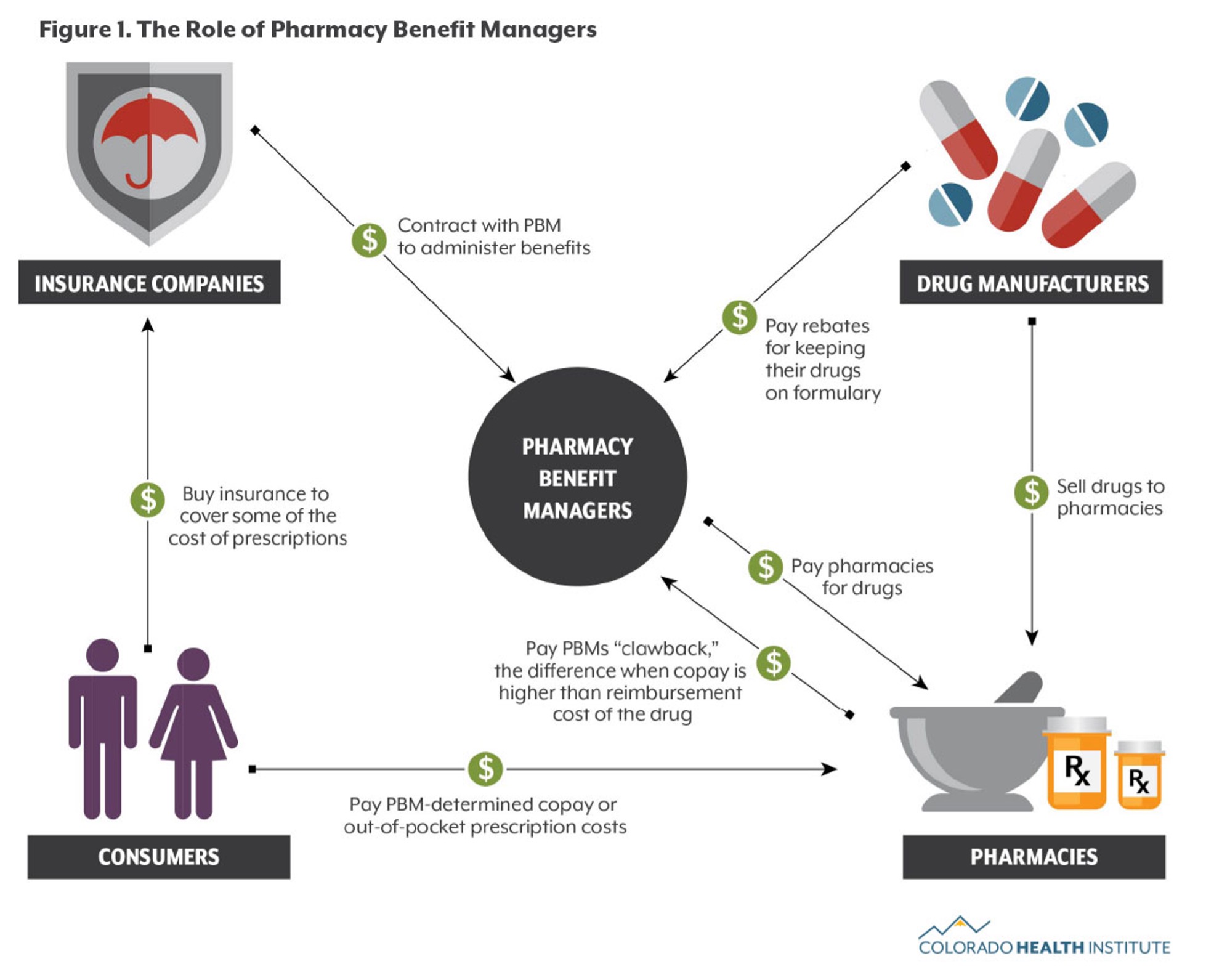

Pharmacy benefit managers are the middlemen of the prescription drug industry, situated as the go-between among pharmacies, drug manufacturers, and insurers. Positioned at the center of the United States pharmaceutical system, PBMs “are hired to negotiate rebates and fees with drug manufacturers, create drug formularies and surrounding policies, and reimburse pharmacies for patients’ prescriptions.”[3] A graphic from the Colorado Health Institute helps explain the relationships PBMs have with pharmacies, drug manufacturers, insurance companies, and ultimately consumers[4]:

As the Colorado Health Institute graphic details, PBMs sit at the heart of prescription drug transactions.

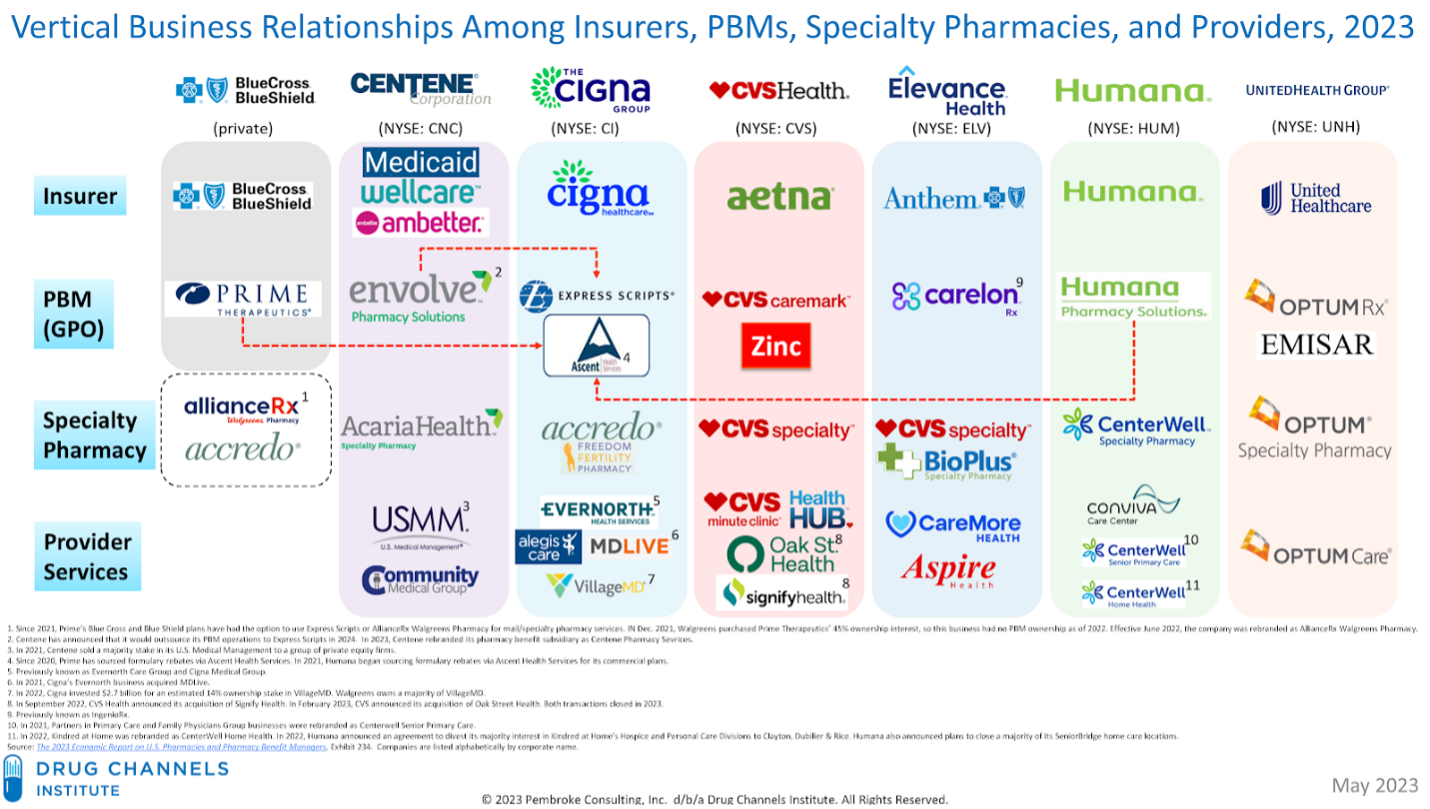

Traditionally, a key for consumers’ ability to obtain prescription drugs at fair prices, was that each of these entities in the chart above were separate companies, thus forcing competition—including price competition—among the various players in the pharmaceuticals market.[5] However, the PBM market, and in turn the broader pharmaceuticals market, has recently been experiencing rapid consolidation where, through a series of vertical mergers, companies are bringing PBMs and pharmacies together under the same corporate umbrella. For example, the largest PBM in the United States – Caremark – is now owned and operated by CVS Health, which also owns the largest retail pharmacy in the United States.[6]

Yet it is not just vertical integration between PBMs and pharmacies that has swept through the pharmaceuticals market; PBMs have also been increasingly vertically integrating with insurance companies. In the past decade, the second and third largest PBMs, Express Scripts and OptumRX,[7] have both been absorbed by major health insurers: OptumRx by UnitedHealth, the largest health insurance company in the U.S. by market share,[8] and, Express Scripts by Cigna, which is now considered one of the 30 largest companies by revenue, worldwide.[9] Indeed, one dataset shows that between 2010 and 2018, vertical integration between Medicare Part D insurers and PBMs increased from around 30% to 80%.[10] The following chart from the Drug Channels Institute highlights the increasingly common vertical business operations between insurance companies, PBMs, and pharmacies[11]:

In light of this market concentration, the PBM market has restructured itself enabling the diminishment, if not absence, of rigorous price competition. The nation’s three largest PBMs – CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx – control nearly 80% of the market, concentration which alone suggests sufficient market power which PBMs can wield to extract excessive profits.[12] And, as the chart above describes, these PBMs have either corporate or contractual vertical relationships with specific pharmacies and insurers that help to further concentrate that market power. This is similar to the type of consolidation being successfully challenged by private plaintiffs in a formerly untouched territory—mergers. As Judge Durkin of the Northern District of Illinois recently noted with respect the Sprint-T-Mobile merger “In a market with high barriers to entry, transparent pricing, and signaling between competitors, these structural changes exacerbated the risks of price coordination.”[13]

It is this rapid and increasing series of vertical mergers and integrations between pharmacies, PBMs, and insurers that has raised competitive concerns, catching the attention of the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) and state regulators. For decades, the FTC has treated PBMs as generally beneficial to competition. Now, in light of these competitive concerns driven by increasing regulatory interest by states, politicians, and members of the public, the FTC is reevaluating its prior stance and position statements.

PBMs and the FTC: A History

For nearly two decades, the FTC’s position on PBMs’ has been one of support. Between 2000 and 2014, in eleven letters and reports, the FTC advocated for PBMs, and against federal and state proposals to increase PBM transparency, on the belief that PBMs delivered lower prices to consumers in their purchases of prescription drugs.[14] In 2005 the FTC published a report titled “Pharmacy Benefit Managers: Ownership of Mail-Order Pharmacies” which found that prescription drug plan sponsors generally paid lower prices for drugs purchased through PBM-owned mail-order pharmacies than for drugs purchased through mail-order or retail pharmacies not owned by PBMs. The findings led the FTC to conclude that PBM ownership of pharmacies did not result in higher costs for consumers, with then-FTC Chair Deborah Platt Majoras noting that: “health insurers manage their drug costs by choosing among a variety of PBM services and service providers.”[15]

Despite these promising early findings, even as early as 2005, the PBM market structure gave cause for concern. Then, as today, the PBM market was dominated by a “big three”—Medco Health Solutions, Caremark Rx, and Express Scripts—controlling just over 50% of the market.[16] Just five years later, in 2011, Express Scripts announced its intention to acquire Medco,[17] a deal which was consummated with the FTC’s blessing in April 2012,[18] and which further concentrated market power in the PBM market, creating the then largest PBM in the U.S.[19]

However, from 2015 onwards, the FTC was increasingly silent; largely refraining from issuing public policy statements. While the FTC remained silent on its prior PBM advocacy initiatives, other governmental bodies increasingly scrutinized the burden that PBMs placed on the pharmaceutical supply chain. The House and Senate, for example, considered H.R. 2376, the Prescription Pricing for the People Act of 2019 which would have required the FTC to study PBMs and whether their practices in negotiating drug prices were anticompetitive.[20] The increasing scrutiny on PBM business practices has been a rare source of bipartisan interest and cooperation. For example, earlier this year, the Senate Finance Committee held a hearing that showed bipartisan agreement that PBMs are directly contributing to today’s drug affordability and access crisis.[21]

Now, in no small part due to the structural changes in the PBM market, and the increasingly glaring effects on end consumers, the FTC is in the process of reevaluating its stance on pharmacy benefit managers. In June 2022, the FTC announced an inquiry into the PBM market, focused on the impact of vertically integrated PBMs on the access and affordability of medicine.[22] As part of this study, the FTC required the six largest PBMs —CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, OptumRx, Humana, Prime Therapeutics, and MedImpact— which together control a whopping 96% of the PBM market,[23] to provide information and records with respect to their business practices. This inquiry has since been expanded to include three group purchasing organizations affiliated with existing PBMs.[24]

A year later, in July 2023, the FTC issued a statement that included a sweeping warning against reliance on any of its former PBM advocacy and position statements, a stark about-face from its prior decades of advocacy and silent acquiescence.[25] This FTC statement was a direct response to PBM and PBM-related organization’s advocacy against any regulation of the industry, particularly by state regulators. The FTC’s Commissioners voted 3-0 during an open meeting to issue this statement withdrawing prior PBM advocacy by the FTC.[26]

In its 2023 statement, the FTC highlights structural factors, noting how “current market structures and business practices may undermine patients, pharmacies, and fair competition.”[27] Specifically the concerns the FTC voices are two-fold: “(1) “how PBMs may be using market power to undermine competition from independent pharmacies”; and, (2) “the role of PBMs in determining the prices consumers pay for prescription drugs, including the impact of PBM rebates.”[28]

FTC Chair Lina Khan, in her corresponding statement on PBMs, notes that the FTC has “received over twenty-four thousand comments from pharmacies, doctors, and patients.”[29] Among the harms identified by these comments regarding PBMs include “competing pharmacies have shared that that PBMs impose unfair fees and clawbacks, impose byzantine contracts that often reimburse pharmacies less than their costs of acquisition, and steer patients to PBM-owned pharmacies”; doctors noting that “PBMs impose unnecessary and burdensome prior authorization and other administrative requirements”; and accusations that PBMs are “harming patients by extracting rebates and fees in exchange for refusing to cover generic and biosimilar drug products, ultimately raising the price that consumers pay for medicines.”[30]

Ultimately, the FTC and its Commissioners are making clear that the prior status quo with PBMs is under intense study and investigation. Instead of a laisse faire attitude to PBM consolidation and rising drug prices, the FTC has now focused on these PBMs and their competitive harm to the pharmaceutical market, as well as to every American consumer feeling the rising drug costs.

PBMs and the FTC: Looking forward

With the FTC launching its 2022 inquiry into the PBM market, and now its recent guidance withdrawing its previous positions, it seems clear that the FTC may be the driver’s seat to move on a more aggressive track. The FTC has a number of paths forward, all starting with its issuance of its study on the PBM market. This study, as noted above, has expanded in scope. But more importantly, with the withdrawal of its previous guidance, the FTC is signaling where the study is likely to land – with the conclusion that PBMs contribute to artificially raising drug prices and the vertical integrations in the pharmaceutical market harms competition, the market, and ultimately consumers.

What the FTC does after the study is anyone’s guess, but American consumers concerned with drug prices may be hopeful that the FTC will continue to take an aggressive stance with the PBMs, particularly if it launches formal litigation against some or all of the major PBMs. But it is not just the FTC that may act going forward – many state regulators have been signaling that they may pursue litigation against the PBMs but were limited in options due to the FTC’s previous guidance. With that prior guidance now gone, along with the upcoming release of the FTC study, state regulators will now have more tools available to challenge PBMs market concentration and business practices that harm every American consumer in the form of higher drug prices, insurance premiums, and copays.

Ultimately, the FTC has the ability to right a historic, although less publicly known, wrong. Given the aggressive stance taken in its 2022 study statement and more recent 2023 statements, the FTC may finally be reaching into its regulatory toolbox to challenge PBMs’ critical role in increasing drug costs. This is scrutiny will be seen as good news for everyone, everyone—except the PBMs, that is.

*Mandy Boltax and Theodore DiSalvo are Associates in Washington, DC

Footnotes

[1] Rising Costs of Prescription Drugs Could Drive Alternate Options, Wolters Kluwer (June 9, 2023) https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/rising-costs-of-prescription-drugs-could-drive-alternate-options#:~:text=One%20report%20from%20the%20US,day%2Dto%2Dday%20lives.

[2] Michael Erman & Julie Steenhuysen, Exclusive: Drugmakers to Raise Prices on at Least 350 Drugs in U.S. in January, Reuters (Dec. 30, 2022), https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/drugmakers-raise-prices-least-350-drugs-us-january-2022-12-30/; Skyrocketing Drug Prices: What's Driving Up Costs?, Association for Accessible Medicines, https://accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/skyrocketing-drug-prices-whats-driving-costs (last accessed Oct. 30, 2023).

[3] FTC Launches Inquiry Into Prescription Drug Middlemen Industry, Federal Trade Commission (June 7, 2023), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2022/06/ftc-launches-inquiry-prescription-drug-middlemen-industry.

[4] Understanding Pharmacy Benefit Managers: As Drug Prices Soar, Policymakers Take Aim, Colorado Health Institute (Mar. 10, 2023), https://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/research/understanding-pharmacy-benefit-managers.

[5] For example, according to the Congressional Budget Office, nationwide spending on prescription drugs has increased from $30 billion in 1980 to $335 billion in 2018 (as expressed in 2018-dollar terms). Over that same period, real per capita spending on prescription drugs increased more than seven times – from $140 to $1,073. Prescription Drugs: Spending, Use, and Prices, CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE (Jan. 21, 2022), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57772.

[6] Denise Myshko & Peter Wehrwein, Beyond the Big Three PBMs, 32 Managed Healthcare Executive 12 (Dec. 14, 2022), https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/beyond-the-big-three-pbms; The Top 15 U.S. Pharmacies of 2022: Market Shares and Revenues at the Biggest Companies, Drug Channels (Mar. 8 ,2023), https://www.drugchannels.net/2023/03/the-top-15-us-pharmacies-of-2022-market.html.

[7] Paige Twenter, Top PBMs by 2022 Market Share, Becker's Hospital Review (May 23, 2023), https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/pharmacy/top-pbms-by-2022-market-share.html.

[8] Stephanie Guinan, Largest Health Insurance Companies for 2024, ValuePenguin (Oct. 2, 2023), https://www.valuepenguin.com/largest-health-insurance-companies.

[9] Matej Mikulic, Cigna - Statistics & Facts, statista (Mar. 20, 2023), https://www.statista.com/topics/10691/cigna/#topicOverview.

[10] Abby E. Alpert, Neeraj Sood, & Charles Gray, Disadvantaging Rivals: Vertical Integration in the Pharmaceutical Market (No. w31536)., National Bureau of Economic Research (Aug. 14, 2023). https://healthpolicy.usc.edu/research/disadvantaging-rivals-vertical-integration-in-the-pharmaceutical-market/.

[11] Mapping the Vertical Integration of Insurers, PBMs, Specialty Pharmacies, and Providers: A May 2023 Update, Drug Channels (May 10, 2023), https://www.drugchannels.net/2023/05/mapping-vertical-integration-of.html.

[12] Matthew Fiedler, Loren Adler, & Richard G. Frank, A Brief Look at Current Debates About Pharmacy Benefit Managers, Brookings (Sept. 7, 2023), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/a-brief-look-at-current-debates-about-pharmacy-benefit-managers/ (“The market for PBM services is highly concentrated, with three firms controlling 79% of the market, which almost certainly gives PBMs market power they can use to earn excessive profits.”); PBM Abuses, National Community Pharmacists Association https://ncpa.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/pbm-business-practices-one-pagers.pdf (“In 2021, the top three PBMs controlled approximately 80% of the market.”).

[13] Dale v. Deutsche Telekom, et. al., No. 1:22-cv-03189 at *26 (ND Ill, Nov. 2, 2023)

[14] Statement of Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter Regarding the Commission Statement on Reliance on Prior PBM-Related Advocacy Statements and Reports that No Longer Reflect Current Market Realities, Federal Trade Commission: Office of Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter (July 20, 2023), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/finalbksremarksonftcstatementagainstrelianceonpriorpbmadvocacy7202023.pdf.

[15]FTC Issues Report on PBM Ownership of Mail-Order Pharmacies, Federal Trade Commission (Sept. 6, 2005), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2005/09/ftc-issues-report-pbm-ownership-mail-order-pharmacies.

[16] Report for Interim Study Proposal 2005-149 Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs): Practices and Procedures, Arkansas: Bureau of Legislative Research (Nov. 13, 2006), https://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/Bureau/Document?type=pdf&source=blr%2FResearch%2FPublications%2FHealth+Care&filename=Report+for+Interim+Study+Proposal+2005-149%2C+PBMs+Practices+and+Procedures.

[17] Anupreeta Das, Gina Chon & Anna Wilde Mathews, Express Scripts to Buy Medco for $29.1 Billion, Wall Street Journal (July 21, 2011), https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424053111903461104576459013892952904

[18] FTC Closes Eight-Month Investigation of Express Scripts, Inc.'s Proposed Acquisition of Pharmacy Benefits Manager Medco Health Solutions, Inc., Federal Trade Commission (Apr. 2, 2012), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2012/04/ftc-closes-eight-month-investigation-express-scripts-incs-proposed-acquisition-pharmacy-benefits; Reed Abelson & Natasha Singer, F.T.C. Approves Merger of 2 of the Biggest Pharmacy Benefit Managers, N.Y. Times (Apr. 2, 2012), https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/03/business/ftc-approves-merger-of-express-scripts-and-medco.html

[19] Jaimy Lee, Express Scripts Buys Medco for $29 Billion, Modern Healthcare (Apr. 2, 2012), https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20120402/NEWS/304029961/express-scripts-buys-medco-for-29-billion.

[20] S.1227 - Prescription Pricing for the People Act of 2019, 116th Congress, Congress.gov, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/1227/cosponsors?r=1&s=1; Stephen Barlas, Bipartisan Drug-Patent Bills Ready for Senate Vote, NIH: National Library of Medicine (Sept. 2019), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6705482/#:~:text=S.,provide%20Congress%20with%20policy%20recommendations.

[21] Senate Finance Committee Hearing Illustrates Broad Bipartisan Consensus to Combat Pharmacy Benefit Managers, American Economic Liberties Project (Mar. 30, 2023), https://www.economicliberties.us/press-release/senate-finance-committee-hearing-illustrates-broad-bipartisan-consensus-to-combat-pharmacy-benefit-managers/.

[22] FTC Launches Inquiry Into Prescription Drug Middlemen Industry, Federal Trade Commission (June 7, 2022), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2022/06/ftc-launches-inquiry-prescription-drug-middlemen-industry.

[23] N. Adam Brown, It's Time to Reform the Mysterious PBM System, MedPage Today (Aug. 25, 2023) https://www.medpagetoday.com/opinion/prescriptionsforabrokensystem/106054.

[24] FTC Deepens Inquiry into Prescription Drug Middlemen, Federal Trade Commission (May 17, 2023), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/05/ftc-deepens-inquiry-prescription-drug-middlemen; FTC Further Expands Inquiry into Prescription Drug Middlemen Industry Practices, Federal Trade Commission (Jun. 8, 2023), https://www ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/06/ftc-further-expands-inquiryprescription-drug-middlemen-industry-practices.

[25] FTC Votes to Issue Statement Withdrawing Prior Pharmacy Benefit Manager Advocacy, Federal Trade Commission (July 20, 2023), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/07/ftc-votes-issue-statement-withdrawing-prior-pharmacy-benefit-manager-advocacy.

[26] Id.

[27] Federal Trade Commission, Federal Trade Commission Statement Concerning Reliance on Prior PBM-Related Advocacy Statements and Reports That No Longer Reflect Current Market Realities 2–3 (2023), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/CLEANPBMStatement7182023%28OPPFinalRevisionsnoon%29.pdf.

[28] Id. at 3.

[29] Statement of Chair Lina M. Khan Regarding the Policy Statement Concerning Reliance on Prior PBM-Related Advocacy Statements and Reports, Commission File No. P230100, Federal Trade Commission: Office of the Chair (July 20, 2023), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/StatementofChairLinaMKhanrePBMLetterWithdrawal.pdf

[30] Id.