Calculation of interest in damages claims – compound answers to a (not so) simple question for national courts

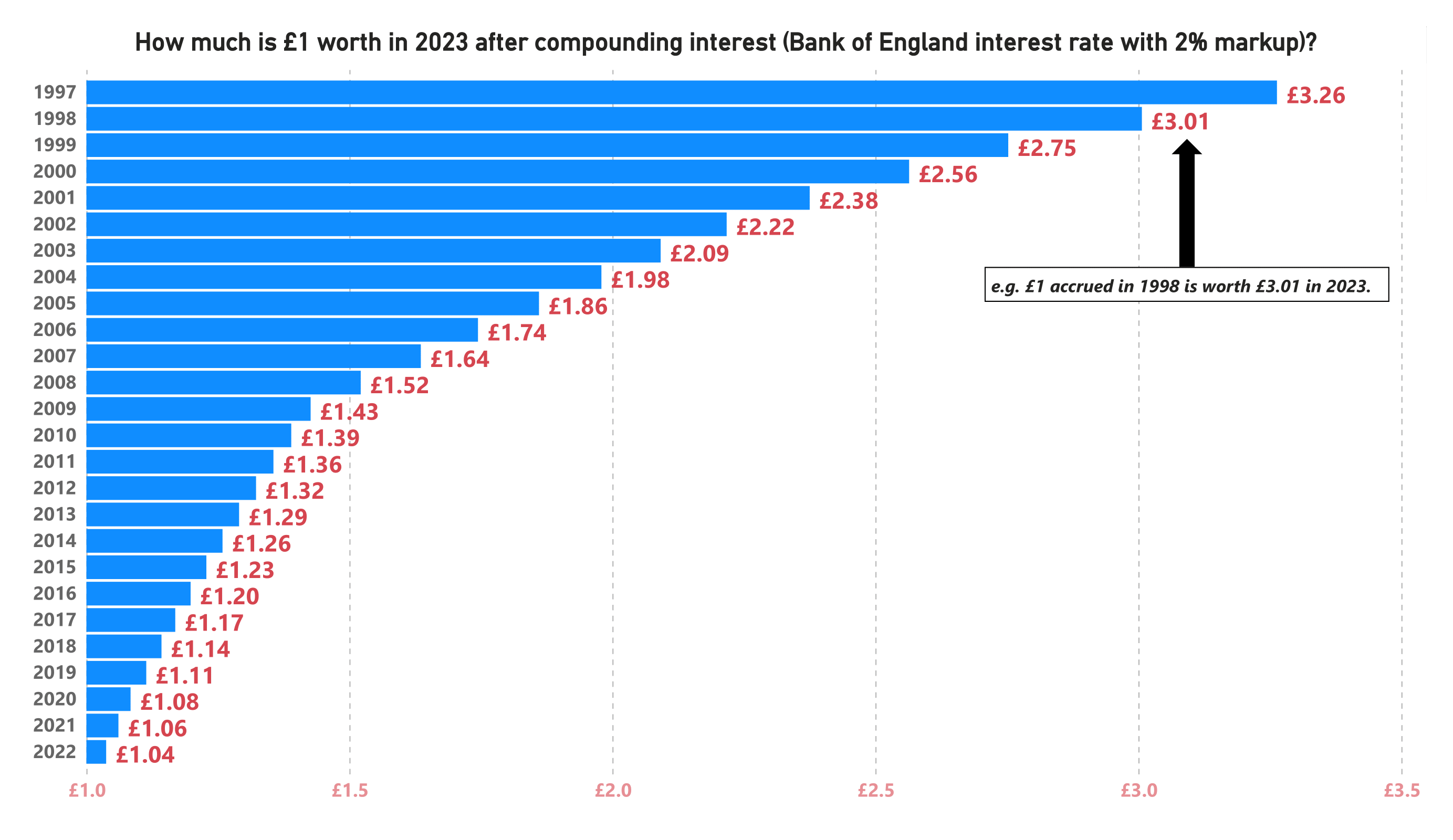

How much is £1 from 1997 worth now? Such a question may appear very simple at the outset. However, ask it twice and you will probably obtain two different answers. Applied in the context of a damages claim in a lawsuit, a number of parameters need to be considered to properly address this question, including what is the interest intended to compensate, what rate should be used, and what methodology should be applied?

Put simply, from an economic perspective, £1 today does not have anywhere near the same value as £1 twenty-five years ago. From a legal perspective, it is necessary to account for that to ensure full compensation when calculating damages stemming from an infringement of competition law. As stated in the often-quoted English House of Lords judgment of Sempra Metals Limited v Inland Revenue Commissioners [2007] UKHL 34, "We live in a world where interest payments for the use of money are calculated on a compound basis. Money is not available commercially on simple interest terms."

The French and English courts have recently handed down important judgments grappling with these issues, and it is instructive to review in tandem the approach taken in each jurisdiction.

In France, the Digicel saga

In 2009, the French Competition Authority (the “ADLC”) imposed a €63 million fine on Orange Caraïbes, a telecom operator in an overseas French territory, and its mother company, France Telecom (“Orange”). Orange was accused of violating Article 102 TFEU between 2000 and 2005 through exclusivity agreements with independent distributors and the only approved repair center for handsets in the French Caribbean. The decision became final in 2015 following a ruling by the French Supreme Court.

Digicel, a competitor that had been ousted as a result of Orange’s anti-competitive practices, filed a damages claim in 2009 against Orange in the Paris Commercial Court, alleging that the practices sanctioned by the ADLC decision had abnormally blocked its development in the mobile telephony market in the French West Indies and French Guyana. Fourteen years later, Digicel’s claim has given rise to a series of judgments from the French courts, with the latest – but not the last – judgment handed down on 1 March 2023. The question of how to calculate interest has been especially heated, confirming that it is a significant issue that requires a careful balancing of both economic and legal considerations.

In a first instance judgment in December 2017[1], the Paris Commercial Court granted Digicel the record sum of EUR 179.64 million in damages, and ruled that interest should be added and calculated based on the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC).

Further to an appeal brought by Orange, the Paris Court of Appeal broadly confirmed the first instance judgment in June 2020, and granted Digicel EUR 173.64 million in damages[2], but rejected the lower court’s approach to calculate interest. This was on the ground that the claimants had not been able to prove that the money they had been deprived of had forced them to restrict their operations or abandon planned investments that would have generated returns equivalent to the amount sought in interest. As a result, the Court of Appeal found that:

- from 1 April 2003 to 31 December 2005, Digicel would have used the amount of money it had been deprived of to reduce its debt. The Court accordingly applied, on a compound basis, the interest rate of 5.3%, corresponding to the average rate paid by Digicel to fund its debt at the time, and

- from 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2018, Digicel had not established what would have been done with the unavailable sum of money and accordingly, the French statutory rates should be applied (still on a compound basis), consistent with French case law.

Both Orange and Digicel then appealed the decision to the French Supreme Court, which handed down its judgment on 1 March 2023.[3] In summary, the Supreme Court almost entirely upheld the judgment from the Court of Appeal, confirming the findings of the Court of Appeal in relation to interest.

Applicable rates

The French Supreme Court confirmed that the burden of proof to obtain compound interest based on the WACC lies with the claimants and that, in this particular instance, Digicel had failed to provide sufficient evidence that this rate should be applied throughout the relevant period. The Supreme court highlighted that Digicel “did not produce any documents to justify that it had used the sums it had been deprived of for intra-group loans whilst profits generated by Digicel had been distributed over the same period". In light of this, the Supreme Court agreed with the Court of Appeal that the claimants had failed to demonstrate the impossibility of financing the said projects from 2006 onwards, and accordingly could not be awarded a higher interest rate. Accordingly, the Supreme Court confirmed that only statutory compounded interest rates should apply from 2006 onwards.

Starting date

The French Supreme Court further sided with the defendants when considering the start date for the calculation of interest. The Court of Appeal indeed took a shortcut and had ruled that interest should start to be compounded from 2003, whilst, according to the Supreme Court, most of the damages were sustained after this date. This was because exclusionary conduct often has long-lasting effects on the structure of the market.

The decision from the Court of Appeal was accordingly overturned and the parties will need to have a separate hearing to determine the exact start date(s) for the purpose of calculating interest on the overall damages. The saga therefore continues…

Of broader interest, the French Supreme Court's decision highlights:

- the importance of claimants providing the relevant evidence to support their claim when it comes to the calculation of interest, and

- the relevant date to take into account when calculating compound interest is the date when the damage was actually suffered by the claimants and not before or after that date.

It is worth noting that the French Supreme Court has repeatedly stressed the importance of providing relevant evidence and using the correct date when calculating compound interest. In fact, another decision from the Court, issued on 1 March 2023,[4] further reinforces these points and highlights their ongoing relevance under French law.

Perspectives from UK courts

The award of compound interest was endorsed by the English courts more than 15 years ago in Sempra Metals, and again very recently by the Competition Appeal Tribunal in the competition context in its judgment dated 7 February 2023 in Royal Mail v DAF Trucks.[5].Royal Mail claimed (in addition to damages, i.e. the overcharge caused by the Trucks cartel) compensation for its financing losses by way of compound interest based on its WACC or, in the alternative, based on its cost of debt and its foregone returns on short-term investments. Royal Mail did provide disclosure of contemporaneous documents relating to their financing decisions, supplemented with factual witness evidence from Royal Mail’s CFO and extensive expert evidence.

First, the CAT confirmed the application of compound as opposed to simple interest, to reflect the “real world” and the economic and commercial reality of businesses. The CAT however rejected the use of the WACC as the appropriate measure of Royal Mail’s financing losses. The CAT considered that the legal test (first set out in Sempra Metals) is that “the “actual losses” suffered by Royal Mail must be based on “actual costs” incurred or paid by Royal Mail in financing the Overcharge.” Using retained earnings [in the calculation of the WACC] may cause loss to its shareholder but Royal Mail itself has not suffered any loss therefrom. Even though the WACC may have been used by Royal Mail to evaluate investments, that only rather emphasises the point that the WACC is a tool for investors to assess investment opportunities.”

The CAT therefore ordered the calculation of compound interest based on a combination of Royal Mail’s cost of debt finance and its returns on short term investments made between 1997 – when the Trucks cartel started and the overcharges started being incurred - and 2022, when the trial occurred. The question of the start date for interest was not in issue, as the case related to overcharges made on specific purchases at identifiable points in time.

The approach of Royal Mail’s expert to calculating interest based on cost of debt finance and its returns on short term investments. was described by the CAT as “a very binary approach.” For the period from 1997 to 2007/08 the rate was wholly based on Royal Mail’s actual returns achieved on various short term investments – as at that time Royal Mail was a net investor. For the period 2008/09 to the present, the rate was entirely based on Royal Mail’s cost of debt – because from 2007 Royal Mail became a net borrower. The CAT, however, endorsed this approach, considering it was “based on how a rational business such as Royal Mail would have used extra funds that it had at the relevant time.” Importantly, the CAT considered that it was “credible on the evidence and it would therefore be more likely that Royal Mail would use the funds in one direction rather than two.”

The resulting award of interest was very significant, as the defendants were ordered to pay Royal Mail over £15.7 million in damages and more than £19 million in interest[6]. It was therefore well worth the effort of adducing the required evidence, given the sums at stake, especially given the age of this cartel.

Interestingly, the CAT’s findings confirm that, before the English courts claimants should not have to prove exactly how they would have used the unavailable money, but instead should provide sufficient evidence to allow inferences to be drawn. In other words, the claimants need to convince a court that the hypothetical decisions on which their interest calculations are based would be more likely than not to occur.

Comment

Given the huge sums often at stake, contrasting the English and French approaches to calculating interest, as evidenced in these judgments, shows that the judicial treatment of this issue is a highly relevant, and sometimes even crucial, consideration for claimants when considering the jurisdiction in which to file claims. Both decisions also highlight that the key driver in maximizing recovery of interest remains adducing appropriate evidence. Whilst this is nothing new in English litigation, where extensive disclosure orders force parties to identify documents relevant to the issues in the claim, this burdensome exercise may cause more consternation on the continent, where disclosure tends to be much more limited in scope.

The proportion interest makes up of a Claimant’s damages in cartel damages claims may start to wane slightly in the coming years as those cartels fall increasingly into the decade and a half of low interest rates after the financial crisis. However, more recent trends in interest rates, if they persist, suggest that even if that does occur, any reduction in the amount of interest recovered as a proportion of damages is likely to be short-lived. In the long run it will therefore likely continue to be well worth the effort of evidencing and obtaining the highest possible interest award.

Finally, and to further illustrate how much can be at stake, we return to the question raised at the beginning of this article, on the present-day value of £1 from 1997. We know that not everyone is as passionate about number crunching as we are, especially among the legal community. You may therefore be glad to read that we have summarized in a handy chart, just how much £1 from 1997 and every year thereafter, is worth today (minus inflation, of course), after applying a typical Bank of England base rate plus 2%:

*Tom Bolster is Partner, Amandine Gueret is Counsel, and Antoine Riquier is a Senior Associate in London.

Footnotes

[1] Paris Commercial Court, 18 December 2017, RG n° 2009016849.

[2] Paris Court of Appeal, 17 June 2020, RG 17/23041.

[3] French Supreme Court, 1 March 2023, 20-18.356, ECLI:FR:CCASS:2023:CO00160.

[4] French Supreme Court, 1 March 2023, 22-16.329, ECLI:FR:CCASS:2023:CO00159.

[5] [2023] CAT 6.

[6] Case 1284/57/18 (T) - Order of Mr Justice Green dated 3 March 2023 (Damages and Interest - Royal Mail).