Supreme Court declines to consider changes to rule 23(B) predominance requirements

On April 15, 2024, the United States Supreme Court declined to review a recent decision of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals affirming class certification in a decade’s long dispute over ATM fees. The class certification appeal arises out of the National ATM Council, Inc., et al. v. Visa Inc., et al. (D.D.C.) litigation. The appeal concerned the appropriate standard for assessing predominance under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(b)(3). By declining to review the D.C. Circuit’s decision, the Supreme Court retained the status quo on already stringent class certification requirements. The Defendants had sought to heighten the standard for class certification, requiring plaintiffs to establish that their evidence proved classwide injury through common proof. The denial to review the decision leaves in place the D.C. Circuit’s analysis where trial courts continue operate as gatekeepers of common issues, and once that is satisfied, allow juries to continue to be the ultimate adjudicator of facts.

Case background

Automatic teller machines (“ATMs”) are particularly important for individuals who bank when banks are traditionally closed, like afterhours or the weekends. When an individual uses an ATM, they might use an ATM owned and operated by their own bank, or they might use an ATM that is not affiliated with their bank. In the latter case, a customer using a non-affiliated ATM might have to pay an “access fee” to withdraw cash from the non-affiliated ATM as the cost of the transaction. This is referred to as a “foreign” ATM transaction. When a foreign transaction is initiated, the ATM terminal must communicate with the customer’s bank through an ATM network.

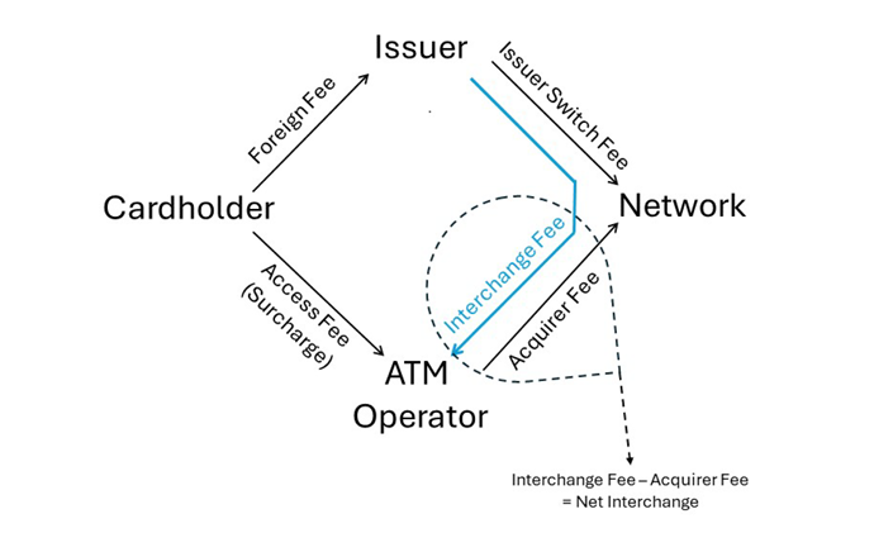

A foreign ATM transaction, when initiated, triggers communications on an ATM network and facilities the charging and recovery of fees. There are not only the access fees charged to the customer, but fees between the bank (or “issuer”), the ATM network, and ATM terminal (or “operator”). These entities charge and deliver fees across the transaction and entity. The following graphic shows the routing of fees between each entity in a foreign ATM transaction:

The defendants in this litigation – Visa and Mastercard – own and operate several ATM networks. As a contractual condition of accessing Visa and Mastercard’s networks, they impose non-discrimination provisions in those contracts, often referred to as the “ATM Access Fee Rules.” The rules were first adopted in 1996 and have remained largely unchanged. Put simply, these rules prohibit ATM terminals/operators from charging access fees for transactions processed over Visa or Mastercard ATM networks that are higher than any access fee the ATM terminals charge for transactions processed over alternative networks. The plaintiffs alleged that Mastercard and Visa charge higher network fees than their competitors. Because of these higher fees, ATM terminals/operators receive less net-interchange revenue when a transaction is routed over a Mastercard or Visa network than if the same transaction occurred on another network. However, more than half of all domestic ATM withdrawals are routed over Mastercard or Visa networks. Thus, an ATM operator that forgoes access to Mastercard or Visa networks risks being unable to process transactions for, and earn revenue from, many cardholders and banks. ATM operators would presumably favor other ATM networks that offered network services for a lower cost, but lower cost networks are barred by the Access Fee Rules if an ATM operator processes any transactions over a Visa or Mastercard network.

In 2011, a number of plaintiff groups filed a lawsuit challenging Visa and Mastercard’s ATM Access Fee Rules, alleging that these rules unreasonably restrain trade and thereby violate Section 1 of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1. The litigation involves three groups of plaintiffs alleging slightly different harms, but otherwise share the same factual predicates: 1) the National ATM Council, an association of independent ATM operators suing on behalf of its members, in addition to thirteen independent ATM operators; 2) the Mackmin consumers, a class of individuals and entities that paid unreimbursed access fees directly to any defendant or “bank co-conspirator” for a foreign ATM transaction; and 3) the Burke consumers, a class of individuals who were charged an access fee for a domestic cash withdrawal transaction at an independent ATM who were not fully reimbursed by their bank.

Procedural history

In 2021, the District Court granted class certification to each of the three proposed classes after they had moved for class certification under Fed. R. Civ. Pro. 23. The dispute at the class certification was whether the plaintiff groups had successfully demonstrated “that questions of law or fact common to the membe3rs of the class predominate over any questions affecting only individual members and that a class action is superior to other available methods of adjudication of the controversy.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(3).[1] The defendants did not challenge class certification under Rule 23’s numerosity, commonality, and typically requirements, just the predominance requirement. National ATM Council, Inc., et al. v. Visa Inc., et al., Case Nos. 11-1803 (RJL), 11-1831 (RJL), 11-1882 (RJL), 2021 WL 4099451 at *3 (D.D.C. Aug. 4., 2021).

The District Court analyzed the facts and evidence for Rule 23(b)(3)’s predominance requirements and found that all three plaintiff groups had met the appropriate burden at the class certification stage. Id. at *5. The contested issue of predominance turned on whether there was sufficient common evidence of resulting injuries and the amount of those injuries. Id. After review, the District Court found that each group had met that burden, particularly because each group’s expert witness had submitted reports outlining the common impact of damages and the quantity of damages for each group. Id. at *6. The court found that plaintiffs need not show that the common questions of injury and damages will be answered in the affirmative on the merits before a jury, just that the questions to each class predominated. Id.

Appeal

In light of the District Court’s certification of each of the three proposed classes, Visa and Mastercard appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. In an unpublished opinion last year, the D.C. Circuit affirmed the District Court’s certification of the three classes. National ATM Council, Inc., et al. v. Visa Inc., et al., 2023 WL 4743013 (D.C. Cir. 2023). The key issue on appeal was whether the District Court failed to give a “hard” or “close look” at the plaintiffs’ evidence or to perform a “rigorous analysis” as to whether plaintiffs met the predominance requirement. Id. at *4. Defendants also asserted that the District Court “erroneously deferred the issue of classwide injury to the merits stage”; that the court had abused its discretion in finding predominance; and, that the evidence indisputably shows each class contained uninjured members. Id.

The D.C. Circuit analyzed the class certifications under the controlling Supreme Court precedent, which notes that a “district court may certify a class only if it is convinced ‘after a rigorous analysis’ that the proposed class can ‘satisfy through evidentiary proof’ the requirements of Rule 23(a) and at least one provision of Rule 23(b).” Id. at *5, citing Comcast Corp. v. Behrend, 569 U.S. 27, 33-34 (2013); see Gen. Tel. Co. v. Falcon, 457 U.S. 147, 160-61 (1982). Further, predominance “is satisfied when questions calling for individualized determination are outweighed by questions that are ‘capable of classwide resolution—which means that determination of [their] truth or falsity will resolve an issue that is central to the validity of each one of the claims in one stroke.’” In re Rail Freight Fuel Surcharge Antitrust Litig.-MDL No. 1869 (Rail Freight II), 934 F.3d 619, 622 (D.C. Cir. 2019) (quoting Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, 564 U.S. 338, 350 (2011)).

Defendants Visa and Mastercard instead argued for a more stringent standard suggesting that the District Court improperly deferred determining whether the plaintiffs’ injury models can prove classwide injury through common proof to the merits stage. Id. As the D.C. Circuit analyzed, the District Court evaluated the evidence proposed by each class that shows their claims were susceptible to common proof, including by reviewing and assessing the reliability of each expert report. Id.

According to the D.C. Circuit, defendants sought a too stringent predominance standard because at the class certification stage, Rule 23(b)(3) requires a showing that questions common to the class predominate, not that those questions will be answered, on the merits, in favor of the class. Id., citing Amgen Inc. v. Connecticut Retirement Plans and Trust Funds, 568 U.S. 455, 459 (2013). Ultimately, the D.C. Circuit held the District Court approved the plaintiffs’ evidentiary case as “reasonable” and based on “well established,” “well-accepted methodolog[ies]” showing class-wide injury. Id.

After the D.C. Circuit’s opinion affirming the District Court’s grant of class certification, defendants Visa and Mastercard petitioned the Supreme Court for review. The Supreme Court declined. One of the key motivators for the appeal, according to Visa and Mastercard’s petition, was that the D.C. Circuit’s opinion created a circuit split on the predominance requirements. See Petitioner Br. 13-24. The Petitioners Visa and Mastercard argued that the Second, Third, Fifth, and Eleventh Circuits have held that “a class cannot be certified … if [the court] merely finds that the plaintiffs’ proposed method for proving classwide injury is plausible or well established.” Pet. 13. For example, Visa and Mastercard cited to the Second Circuit’s case In re Initial Public Offerings Sec. Litig., 471 F.3d 24 (2d Cir. 2006), arguing that the Second Circuit requires more than the plaintiff to show a possible method to find predominance, but rather that the district court must resolve factual disputes relevant to each Rule 23 requirement. See Pet. 14-15; In re Initial Public Offerings Sec. Litig. at 41.

In response, the plaintiffs’ respondent brief argued that no such circuit split existed, particularly based on the plain language of the D.C. Circuit’s opinion. See Respondent Br. 20-23. For example, in response to Visa and Mastercard’s citation to In re Initial Public Offerings Sec. Litig., respondents pointed out that the Second Circuit “merely held that the court should resolve disputes about whether the requirements for class certification are satisfied, not which side’s experts will prevail in answering a common question.” Resp. 21. And, in any event, there has since been additional clarification by the Second Circuit on the issue. See In re U.S. Foodservice Inc. Pricing Litig., 729 F.3d 108, 129-30 (2d Cir. 2013). The respondents argue that once one actually looks at the predominance standard set out by the Second, Third, Fifth, and Eleventh Circuits, those standards are the same as the D.C. Circuit’s, and thus no circuit split actually exists.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court declined to review this appeal, leaving in place the D.C. Circuit’s legal framework for analyzing Rule 23(b)(3) predominance requirements. This also is a signal that the suggested circuit split may indeed not exist as Visa and Mastercard argued. This framework is consistent with Supreme Court precedent that requires the trial court to engage in a rigorous analysis about whether individual determinations are outweighed by questions that are capable of class-wide resolution. However, unlike the more stringent standard argued for by Visa and Mastercard, the D.C. Circuit’s predominance standard is consistent with precedent and the practical realities of class certification – namely the court’s function to gatekeep common issues while allowing juries to be the ultimate adjudicators of fact.

*Theodore DiSalvo is an Associate in Washington, D.C.

Footnotes

[1] Additionally, there were disputes at the District Court regarding questions regarding some proposed class representatives and conflicts that were resolved in favor of the plaintiffs.