When ESG meets FSMA: a legal and economic analysis of a simulated case study

The rapidly changing arena of climate and other ESG reporting intersects with potential liability for misstatements under the provisions of Sections 90/90A of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA). Although there has been a lot of commentary, given that the growing number of securities litigation claims are at an early stage, there has been little discussion on how these issues might give rise to losses for investors and, ultimately, commercially viable litigation.

In a special collaboration with Grant Thornton, this article explores the intersection of ESG claims and securities litigation under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. Through a hypothetical case study, it provides key insights and expert opinions on quantifying securities litigation claims in an ESG context.

Securities litigation background

The UK is an exciting jurisdiction for securities litigation generally. Claimants are increasingly looking to utilise the statutory claims provided in FSMA and the cases currently afoot are breaking new ground. In what have been regarded as positive developments for claimants, in 2022, the court ordered a split trial for liability and standing issues first and reliance issues thereafter in two separate securities claims against G4S and RSA. G4S settled in December 2023, shortly before the first six-week trial was due to commence in January 2024.

Two additional high-profile securities claims were filed in 2023 against Glencore and Petrofac on behalf of institutional investors claiming for share price losses, both of which followed Serious Fraud Office bribery convictions. Given the developing regime for securities litigation generally, an increasing number of ESG‑related claims are being issued pursuant to the framework in FSMA. Most recently, in May 2024, a group litigation claim was filed against Boohoo Group plc, alleging breaches of FSMA in relation to the mistreatment of its workers and failures to disclose labour rights violations.

ESG-related claims have been receiving an increasing amount of attention for some time, not least from regulators. In November 2023, the Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA) consultation paper “Sustainability Disclosure Requirements and investment labels” proposed a set of new measures to reduce greenwashing and increase consumer and investor confidence in financial products that make sustainability claims,[1] which resulted in the implementation of the ESG Sourcebook, a set of regulations contained in the FCA Handbook that codifies common standards in relation to the description of green investments. Further, guidance outside the handbook has recently been published by the FCA to coincide with the anti-greenwashing rule which came into force on 31 May 2024. This reflects the trend towards a requirement for increased specificity around ESG statements and the description of green credentials. As what is acceptable becomes codified, the threat of litigation resulting from any deviation from these codified standards grows. There is also discussion about how the increasing ubiquity of securities litigation group-action claims and recent regulatory initiatives have compelled companies to provide detailed and substantiated climate-related disclosures in accordance with guidance to mitigate the risk of directors facing accountability for misleading statements,[2] underscoring the significant reputational consequences of discovered deceit.

Through the lens of a hypothetical case-study, this paper aims to provide would-be claimants with an illustrative analysis of how loss might arise directly in connection with ESG misstatements, and the potential legal bases for seeking recoveries. As references to ESG issues and green credentials have become commonplace, what are the things to look out for in securities issuances from an investor perspective, what would a claim look like in practice and what might its economic value be?

Case study

We focus on the activities of a fictional company, GreenWash Plc, which produces personal cleaning products.[3] GreenWash’s business claims to be based on the production of sustainable and environmentally friendly personal cleaning products. Its sustainability and environmental credentials are central to its market offering.

GreenWash was operating as a private limited company with the equity owned by its founders. Following years of revenue growth, capacity expansion and profitability increases, the founders decided to take GreenWash public. GreenWash issued its share Prospectus for an Initial Public Offering (IPO) on 1 November 2019. It contained the following statements:

- GreenWash has an ongoing monitoring process in place for all its subcontractors to ensure that all raw materials come from sustainable sources and are environmentally neutral.

- Scope 3 emissions for GreenWash as well as all of its subcontractors are within specified limits, with subcontractors audited annually to ensure that this remains the case.

- GreenWash recognises the importance of climate change to its customers and has therefore committed to keeping its emissions and those of its subcontractors and suppliers at specified limits, aligned with the Paris Agreement of 2015.

Ten million shares were issued in the IPO with a target price of £100 per share. The IPO was oversubscribed and the share price rose. The positive publicity around the IPO put GreenWash in the spotlight which it exploited in its marketing. Sales increased and the share price rose further, giving a total market capitalisation of around £1.12 billion or £112 per share.

A profit warning was issued on 15 October 2020. Poor performance was explained away through oblique statements regarding supply/logistics issues following the pandemic. On 19 May 2021, GreenWash was subject to a public regulatory investigation following whistleblower allegations regarding the sustainability of products in its supply chain and the emissions levels of GreenWash’s suppliers. Following further press reporting on the matter on 5 August 2021, it transpired that at the height of the pandemic in 2020, subcontractors operating in GreenWash’s supply chain had sourced raw materials from suppliers known to operate without any concern for environmental or sustainability matters, and whose scope 3 emissions were well in excess of the limits set by GreenWash in its Prospectus.

It was also revealed that the Company’s own emissions pre-IPO had exceeded the limits set in the Paris Agreement. Worse still, there was evidence that all of this had been known by GreenWash’s senior management, including its founder/CEO, who had instigated an internal investigation in early 2020.

Following a report and fine from the regulator on 11 December 2021, the Company acknowledged that it had concluded its internal investigation (coinciding with the public regulatory investigation) to reveal that a proportion of its products had been produced using raw materials from the same suppliers since before the IPO. That proportion increased substantively during the pandemic. GreenWash claimed not to have been aware of the suppliers’ presence in their supply chain until the conclusion of its internal investigation. Commentators expressed doubt at this given the duration and scale of the suppliers’ involvement.

Marked falls in GreenWash’s share price were observed at three key points. The first was when the whistleblower allegations were made on 19 May 2021. The second followed the resulting press coverage on 5 August 2021. The third followed the culmination of the investigation and the issuance of a regulatory fine on 11 December 2021. The timeline of key events is summarised in the table below:

|

Date |

Description |

Internal or Public |

|

Pre-IPO |

GreenWash had not met its emissions targets and had been obtaining raw materials from non-compliant suppliers. |

Internal |

|

1 November 2019 |

IPO including statements that raw materials are from compliant suppliers and emissions targets had been met. |

Public |

|

March 2020 |

GreenWash sources significant quantities of raw materials from non-compliant suppliers. Internal report on the matter produced. |

Internal |

|

15 October 2020 |

Profit warning issued. |

Public |

|

19 May 2021 |

Whistleblower allegations relating to suppliers and launch of investigation. |

Public |

|

5 August 2021 |

New information revealed in press reporting about extent of non-compliant supplier use. |

Public |

|

11 December 2021 |

Regulatory fine and report issuance setting out full nature of the infringement. |

Public |

While share price decreases were observed at each of these points, the share price impact was most pronounced following the publication of whistleblowing allegations.

Investors bought, sold and retained shares throughout the time period set out above and in several specific settings: some directly subscribed to the IPO; some purchased or elected to retain shares in the after-market of the IPO; and some purchased or elected to retain shares during the longer course of the factual revelations over 2021 and 2022.

Investors incurred losses due to the declining share price of GreenWash. This is because GreenWash’s investors depended on the information provided by the Company to guide their investment decisions. GreenWash’s statements regarding its green credentials and the sustainability of its supply chain – both in the IPO prospectus and subsequently – had a positive effect on the market price of the Company’s shares. If any of these statements were false, it would mean that the share price had been artificially inflated during the period that the market had been misled. This artificial inflation would have persisted until a corrective disclosure was made to the market, i.e., until the market knew the truth. Consequently, any investor who bought shares during the period of inflation and subsequently sold them after the corrective disclosure occurred or who continued to hold them until all inflation was eroded, would experience a loss. Furthermore, investors who purchased shares before the inflation and retained their shares based on this information could still have incurred losses if they sold their shares after the correction had taken place and made a decision to hold the shares based on the false statement.

We set out below the legal framework within which GreenWash’s investors could recover their losses and an economic framework for how such losses might be quantified.

Legal analysis by Hausfeld

Statutory Regime

Ensuring that markets operate on the basis of complete and accurate information is an essential part of their proper functioning. Legal regimes have long since existed in order to provide investors with protection, should issuers fail to inform the market fully or accurately, whether in the context of a prospectus (the contents of which are prescribed in statue and regulation) or the publication of more general market information (for example annual reports).

Prospectus Claims – Section 90

The essential requirements of a prospectus are set out in s80 FSMA. The prospectus must contain “all such information as investors and their professional advisers would reasonably require, and reasonably expect to find there, for the purpose of making an informed assessment of (a) the assets and liabilities, financial position, profits and losses, and prospects of the issuer of the securities; and (b) the rights attaching to the securities”.

Further detail as to the required content of prospectuses is set out in the FCA’s Listing Rules.[4]

For an organisation such as GreenWash, where sustainability and environmental credentials are at the forefront of its offering, statements concerning these aspects of the business would likely fall under the wide ambit of s80 FSMA. Potential liability to shareholders for misstatements in a prospectus arises under s90 FSMA:

“90 Compensation for statements in listing particulars or prospectus

(1) Any person responsible for listing particulars is liable to pay compensation to a person who has—

(a) acquired securities to which the particulars apply; and

(b) suffered loss in respect of them as a result of—

(i) any untrue or misleading statement in the particulars; or

(ii) the omission from the particulars of any matter required to be included by section 80 or 81.

(2) Subsection (1) is subject to exemptions provided by Schedule 10.”

Were the statements in the Prospectus untrue and/or misleading?

The regime imposing liability for misstatements in a prospectus is more prescriptive than that which applies to misstatements to the market. This is for several reasons, the main being that a prospectus effectively serves as a sales pitch by an issuer, to promote securities at the point that they are offered to the market. In that sense, the prospectus is taken to inform the entire market about the nature of the proposed investment and so is required to contain certain threshold information.

Having regard to those threshold requirements, the statements made by GreenWash regarding the monitoring processes to ensure its subcontractors used sustainable raw materials and its level of scope 3 emissions would likely be actionable misstatements. The failure to mention the true nature of raw materials in GreenWash’s supply chain would likely be an actionable omission. Given the centrality of sustainability to GreenWash’s offering, investors could argue they would reasonably require or expect to find any contradictory information in the Prospectus pursuant to s80 FSMA. From an institutional investor’s perspective, the increasing pressure from stakeholders to make green investments in companies such as GreenWash magnified the adverse impact of the statements and omissions from the Prospectus. GreenWash held itself out to be unique on the basis of its environmental credentials which turned out to be false.

Schedule 10 FSMA contains a number of defences to s90, most notably the “reasonable belief” defence – if GreenWash can satisfy one or more of the requirements in Schedule 10 paragraph 2 then any claim will be defeated. Although many material interpretation issues in relation to s90 FSMA claims remain undecided, a sensible assumption would be for the court to apply a common law negligence standard when considering whether GreenWash had a reasonable belief in the accuracy of statements made in the prospectus, or in the correctness of the omission.

Assuming shareholders can make good on the Prospectus containing untrue/misleading statements or omitting any required particulars then the burden of proof will be on GreenWash to try and establish a reasonable belief defence. There is no obligation on shareholders to prove reliance on the misstatements/omissions under s90 FSMA. By way of further contrast, s90A FSMA expressly requires that claimants bought, held, or sold securities “in reliance” on published information.

Importantly, even if a prospectus is compliant with the Listing Rules, that will not necessarily mean avoidance of liability under s90.

Misleading Statements – Section 90A

Potential liability is incurred by issuers in relation to misstatements in “published information” to the market under s90A and Schedule 10A, as follows:

90A Liability of issuers in connection with published information

Schedule 10A makes provision about the liability of issuers of securities to pay compensation to persons who have suffered loss as a result of—

(a) a misleading statement or dishonest omission in certain published information relating to the securities, or

(b) a dishonest delay in publishing such information.

… (and at Schedule 10A)

3(1) An issuer of securities to which this Schedule applies is liable to pay compensation to a person who—

(a) acquires, continues to hold or disposes of the securities in reliance on published information to which this Schedule applies, and

(b) suffers loss in respect of the securities as a result of—

(i) any untrue or misleading statement in that published information, or

(ii) the omission from that published information of any matter required to be included in it.

(2) The issuer is liable in respect of an untrue or misleading statement only if a person discharging managerial responsibilities within the issuer knew the statement to be untrue or misleading or was reckless as to whether it was untrue or misleading.

(3) The issuer is liable in respect of the omission of any matter required to be included in published information only if a person discharging managerial responsibilities within the issuer knew the omission to be a dishonest concealment of a material fact.

(4) A loss is not regarded as suffered as a result of the statement or omission unless the person suffering it acquired, continued to hold or disposed of the relevant securities—

(a) in reliance on the information in question, and

(b) at a time when, and in circumstances in which, it was reasonable for him to rely on it.

Applying this to the case study, the profit warning issued by GreenWash in October 2020 blamed high-level factors such as supply/logistics issues at a time when its internal investigation into its supply chain had been running for a number of months. From GreenWash’s investors’ perspective, the profit warning should have addressed the supply chain issues. This would likely have constituted a dishonest omission under s90A(a) and/or a dishonest delay under s90A(b). The fact that GreenWash’s CEO had instigated an internal investigation in early 2020, but investors remained unaware of the issues until publication of the whistleblower allegations in May 2021, would likely be enough to establish a case against GreenWash, including in relation to the requirement concerning the knowledge of a person discharging managerial responsibility within GreenWash (as provided at paragraph 3(2) of Schedule 10A) – in this case its CEO.

Measure of losses

There is no direct judicial authority in England and Wales which enables claimants to know the legal basis upon which losses in the context of section 90/90A may be calculated. However, an analysis from first principles provides helpful guidance as to the likely way in which the courts might deal with the issue. We may also look (with caution) to other common law jurisdictions where securities litigation is more mature, and where the practical issues of share trading and the related effects on the calculation of loss have been considered by the courts (such as the USA and Australia).

The first issue to consider is the legal basis upon which loss may be recovered by claimants, i.e., on a measure akin to either negligence or “deceit”. In practice, the deceit measure will usually be the primary basis for any loss claims. Pursuant to this measure, successful claimants would be entitled to recover “all loss directly caused by the transaction [induced by the fraud] and all consequential loss, provided it is not too remote, and that loss is not to be treated as too remote merely because it was not in the contemplation of the representor”.[5] This is open as an argument to GreenWash’s shareholders as a result of case law and historic legislation dating back to the 19th Century, the key components of which have been preserved in s90 FSMA. If the deceit measure applies, GreenWash’s shareholders may be able to recover losses from any price drop of GreenWash shares as a whole, without having to strip out the effects of other factors such as general falls in the market during the relevant period.

A negligence measure of loss would likely be argued in the alternative to deceit. Should a negligence measure of loss apply, recent judgments from senior courts have developed more refined tests for assessment of damages for negligence, especially in the field of economic loss. In that assessment, the key question for claimants in relation to the actions of GreenWash is referred to as the “scope of duty question” – i.e., what are the risks of harm to GreenWash’s shareholders against which the law imposes on the GreenWash a duty to take care? GreenWash might argue that the risks of harm to its shareholders were purely financial. In other words, the untrue/misleading statements or omissions caused the market to value the price of the shares at an inflated level and that only such inflation attributable to the statements or omissions is the value of loss suffered. If a court was attracted to such an argument, it may decide that any value other than that ascribed to the statements the claimants complain of ought to be excluded, along with any impact from external market events and information (other than the misstatements).

Importantly, adducing expert evidence in these claims, which assists the court as to the appropriate basis for assessment and amount of quantum, is a crucial aspect of ensuring that the court is able to reach a reasoned decision.

Economic analysis by Grant Thornton UK LLP - Economic consulting

A key part of any prospective securities class action under the FSMA s90/s90A provisions is to estimate the quantum of damages. The damages in this instance relate to the harm to shareholders as a result of the misstatements, specifically from the share price impact of the misstatements. This could manifest as a dislocation in the share price path between what actually happened and what would have happened if the statements were accurate or indeed if the false claims were never made. In either case, reputational damage and any premium paid on the basis of the false statements would constitute harm. Finally, some individuals who purchased the shares may have opted not to purchase them had they known the true nature of GreenWash’s ESG credentials. In the context of an ESG-related misstatement there may be additional scope for non-financial harm, although such harms are beyond the scope of this paper.

Restricting attention to financial harm, the quantum can be thought of as the difference between the claimants’ financial position that prevailed following the misstatements and the financial position that would have prevailed under a counterfactual, or “but for”, scenario.

The counterfactual scenario can be conceived as a scenario where the correct information was disclosed or where the false statements were actually true.

In the counterfactual scenario, the claimants could have acted differently. For example, in a case where claimants would still have purchased shares in GreenWash under the counterfactual scenario,[6] the quantum is the difference between the actual share price and an estimate of what the share price would have been under the counterfactual. While the prevailing actual share price can easily be observed, the counterfactual share price cannot be observed, and it must therefore be estimated. In this setting, the harm is the causal impact that the misstatement had on the share price of GreenWash.

Another potential outcome under the counterfactual scenario, would be that some claimants may have preferred to hold their money or purchase a different asset if they were not subject to the misstatement. In this setting, the quantum of damages is the difference between the investors’ actual financial position and an estimate of what their financial position would have been under the counterfactual scenario that no misstatement occurred, and a different asset was purchased.

In the remainder of this paper, we will consider the decrease in share price that is attributable to the misstatements. As the GreenWash example shows, such misstatements could occur in a listing prospectus, and/or a wide array of other forms, including annual reports. The important legal distinctions between these media are explained above.

The misstatements introduce artificial inflation which is then unwound through corrective disclosures. Harm is caused by investors purchasing or holding shares at an inflated price and then selling or continuing to hold them after the inflation is gone. The right approach to calculating this loss depends on the legal measure of loss that is adopted but it is typically done using one of three approaches: rescissionary approach, inflation approach or the left-in-hand approach. In general terms, the recessionary approach may be a starting point for the deceit measure for loss, whereas the inflationary and left-in-hand approaches may be more aligned to the negligence measure of loss.

The rescissionary approach seeks all loss that arises from trading/holding the shares over the inflationary period. The inflationary approach seeks the loss that arises specifically as a result of the artificial inflation while trading/holding the shares over the inflationary period. The left-in-hand approach calculates the direct effects of the inflation on the holdings of investors.

The rescissionary approach is therefore the sum across shares purchased of the difference between the price paid and the price sold. The inflationary approach is the sum across shares purchased of the difference between inflation in the price at the point of purchase and inflation in the price at the point of sale. The left-in-hand approach is the sum across corrective disclosures of the product of holdings prior to the corrective disclosure and the price impact of the corrective disclosure.

Both the inflationary and left-in-hand methods require an estimate of the extent of inflation in price over time. To do this one requires an estimate of the causal impact of the events which give rise to the alleged infringement and/or through which the impact of the alleged infringement is unwound. It is typically the latter that is observed whereby a model is used to estimate the impact of each corrective disclosure and these estimates are used to quantify damages.

In this case study, we have elected to present the results applying the left-in-hand approach as the application of either the rescissionary or inflationary methods requires transaction level and the use of transaction matching procedures (typically either last-in-first-out (LIFO) or first-in-first-out FIFO)). A discussion of the intricacies of such methods is beyond the scope of this article. The left-in-hand method typically provides a conservative estimate of loss relative to the rescissionary approach. This is because the rescissionary approach captures the entirety of any adverse share price movement over time whereas the left-in-hand approach captures only the impact of the corrective disclosures on exposed holdings.

Estimating the share price that would have materialised under the counterfactual is not a straightforward task as it cannot be directly observed. Economists use a wide array of quantitative techniques to estimate outcomes under a counterfactual scenario in policy, litigation and academic research settings.

The approaches that are used can be separated into two distinct categories: those that leverage economic theoretical frameworks; and those that use comparator data. Theoretical models use assumptions about how a market works to generate estimates of relevant outcomes. By contrast, comparator-based techniques use data from markets for different entities or at different points in time to generate estimates of relevant outcomes.

In a securities litigation setting, granular data about the value of individual financial assets is accessible, as is detailed information about the companies/economies upon which their value is based. This data is available at frequent intervals of time which creates the opportunity to use comparator-based techniques.

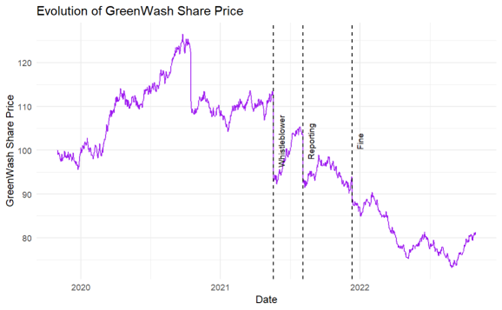

Given the nature of the data available in a securities litigation context, comparator-based quantitative techniques will typically be the appropriate approach. Indeed, the event study approach has been widely adopted as a way through which share price impacts can be quantified in the context of securities litigation. The figure below shows the evolution of GreenWash’s simulated share price:

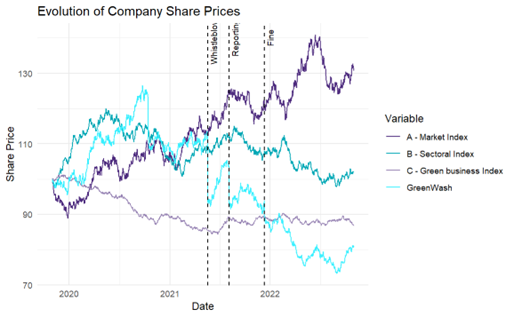

The data presented in this hypothetical example is simulated and has been randomly generated. To create GreenWash’s share price under the counterfactual, it has been assumed that it is linearly related to the value of three comparators: a market index labelled as A, a sectoral index labelled as B and a green business index labelled as C. These indices are intended to proxy for key determinants of GreenWash’s stock price. The market index would be akin to the FTSE 100 and is intended to capture the impact of general market forces. The sectoral index would likely capture key trends that are localised to the cleaning products market. The green business index would likely capture the impact of any developments that would influence firms for which sustainability is a core part of their offering such as is the case with GreenWash. Deviations from this counterfactual are programmed explicitly in the simulated data as a result of the profit warning, the whistleblowing allegations, press reporting and the regulatory finding. The four series are presented in the figure below:

Each of the share prices have been normalised to be equal to £100 on the first day of interest. The values of the market index, sectoral index and green business index have been simulated such that they have characteristics that are typically observed for share prices.

As a result of the conditions of the simulation, the market (A) and sectoral (B) indices grow over time while the green business index (C) does not exhibit any growth and for many periods has negative growth.[7]

The calculated growth rate is applied to the initial value of £100 to arrive at a counterfactual price series for GreenWash prior to any exogenous events. In the fact pattern there are four exogenous events, three relating to the ESG scandal of interest (i.e., the whistleblower allegations, the press coverage and the regulatory investigation and ensuing fine) and one which relates to a profit warning. It is assumed that these events are strictly exogenous and produce one-off growth rate impacts.

For the purposes of the simulation, we have imposed that the profit warning led to a £10 fall in the value of GreenWash’s shares on the day of the event before reverting to the counterfactual growth rate path. It has been imposed that the whistleblower allegations led to a £20 fall in the value of GreenWash’s share price before reverting to the counterfactual growth rate path. The news reporting around the allegations is then imposed to lead to a £10 fall in the value of GreenWash’s share price before reverting to the counterfactual growth rate path. Finally, it is assumed that the regulatory finding led to a further £5 fall in the share price of GreenWash before the growth rate reverted to the counterfactual path.[8]

The first component of an event study is to estimate a market model. Considerations as to the correct model include the length of the training period, the duration of the prediction period, functional form and the selection of variables.

In this example, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression is used to relate the share price index growth rates of A (market index), B (sectoral index) and C (green business index) to that of GreenWash. The resulting model estimated using OLS is a key component of an event study, commonly referred to as the market model. It relates the observed growth rate of the price of GreenWash shares (GreenWash returns) to the returns, on the market and sectoral indices.

This model is then used to estimate a counterfactual growth rate for each date of interest: this is an estimate of how the share price of GreenWash would have evolved if the adverse ESG events did not occur. After the observed share price growth rates of indices A, B and C are fed into the model, it predicts what GreenWash’s growth rate would have been. This counterfactual prediction can then be applied to the pre-event share price to derive what the share price path would have been under the counterfactual. The difference between the observed share price and the modeled counterfactual is then the estimate of the quantum of harm.

The table below summarises the application of this approach. The columns in the table are defined by:

- The date of the corrective disclosure.

- A description of the corrective disclosure.

- GreenWash share price on the eve of the corrective disclosure.

- Change in the GreenWash share price on the day of the corrective disclosure.

- Change in the GreenWash share price on the day of the corrective disclosure that is predicted by the model when it is fed the actual growth rates for the market and sectoral index on the date of the corrective disclosure.

- The GreenWash share price on market close on the day of the corrective disclosure.

- The GreenWash share price implied by the model predicted growth rate (this is calculated as the product of the price of the share on the eve of the event and one plus the expected rate of return.

- The loss per share under the left-in-hand method which is the difference between the actual post-event price and the expected post-event price.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

Date |

Description |

Price on eve of event |

Actual returns |

Expected returns |

Actual post-event price |

Expected post-event price |

Loss per share under the left-in-hand method |

|

19 May 2021 |

Whistleblower allegations relating to suppliers and launch of investigation. |

£112.65 |

-17.08% |

0.21% |

£93.41 |

£112.88 |

£19.47 |

|

5 August 2021 |

New information revealed in press reporting about extent of non-compliant supplier use. |

£103.74 |

-10.76% |

-0.31% |

£92.58 |

£103.42 |

£10.84 |

|

11 December 2021 |

Regulatory fine and report issuance setting out full nature of the infringement. |

£93.95 |

-4.94% |

-0.02% |

£89.31 |

£93.93 |

£4.62 |

Using the model to estimate normal returns and then using the abnormal rate of return to estimate loss per share we have calculated that the impact of the corrective disclosure on 19 May 2021 was £19.47, on 5 August 2021 was £10.84 and on 11 December 2021 was £4.62. Each of these figures is close to the true value which we created when generating the dataset (£20, £10 and £5 respectively).

This is the common approach to estimating loss using the left-in-hand approach. The final step would be to multiply the number of shares held by each investor on the eve of each corrective disclosure by the associated share price impact.

By way of illustration, suppose that an investor owned 100,000 shares in GreenWash on 18 May 2021 and continued to hold these until at least 12 December 2021. This investor would have been estimated to have lost £1,947,298.08 as a result of the first corrective disclosure, £1,084,232.69 as a result of the second and £461,869.91 as a result of the third. In sum this would mean that the exemplar investor was estimated to have lost £3,493,400.68 in total under the left-in-hand method. The theoretical total loss for investors holding all of the 10 million shares would exceed £349,000,000 (excluding any consequential losses that might be available to investors if a deceit measure of loss is adopted).

Conclusion

Although it remains to be seen how the courts will approach issues of loss and quantifying damages in securities litigation, we hope that the GreenWash case study has brought life to what are currently theoretical issues. As it demonstrates, the potential losses are likely be very substantial in the event that claims can be made good. Although the case study assumes the adoption of the left-in-hand approach, in many cases this will give a most conservative total loss figure; if a deceit measure of loss is preferred in conjunction with the rescissionary approach, the relative losses could be even greater.

There is a strong appetite from third-party litigation funders to back high-value ESG securities cases of this nature with good prospects of success. Accordingly, investors can expect to pursue such claims with limited or no costs risk or up-front financial burden. Litigation funders are experienced in bringing similar types of claims in other jurisdictions and, in the competitive market for funding, terms can be tailored to fit the cases as required. As part of that process, after-the-event insurance can be put in place, alongside third-party funding, in order to protect potential claimants from any adverse costs risk.

Due to the complexities of the issues, different loss bases and quantification methodologies, the case study illustrates the necessity of expert legal and economist involvement at the initial stage of any such dispute, which is a prerequisite for any prospective funder.

With special thanks to Schellion Horn and Tom Middleton from Grant Thornton for their invaluable input in co-authoring this article.

Footnotes

[1] For a more complete discussion of this consultation see Hausfeld’s article here: Hausfeld | Greenwashers beware: new FCA proposals will force investment firms to clean up their act

[2] For more information, please refer to Grant Thorton article: https://www.grantthornton.co.uk/insights/greenwashing-new-risks-from-new-reporting-rules-on-esg/

[3] We confirm the case study has been designed for analytical purposes only and all of its contents are fictional. Any resemblance to real life facts or entities is purely coincidental.

[4] https://www.handbook.fca.org.uk/handbook/LR.pdf

[5] Parabola Investments v Browallia Cal Ltd [2010] EWCA Civ 486 per Toulson LJ at para 36.

[6] The counterfactual scenario here is assumed to be the scenario where there was no misreporting and the information the claimant had at the time of purchasing the stock was indeed the correct information.

[7] When constructing these simulated share price indices an assumed long-run trend is used and random volatility is also incorporated. In reality, a Company’s share price is governed by a complex web of relationships, some of which are company-specific while others can be sector or economy-wide. In real world event studies, these relationships will drive the correlation that is observed between share prices with similar underlying determinants. In the interest of simplicity, in this analysis it has been assumed that there is a deterministic relationship between the share price indices A, B and C and that of GreenWash, with a random disturbance term.In the first period the value of A, B and C is set at 100. In future periods, each value is equal to the lagged value multiplied by a growth rate which has a firm-specific component and a normalized random disturbance term. We have assumed that A exhibits higher long-run growth, B more moderate and C with a long-run gradual decline.The growth rate associated with each of these values determines the growth rate for the value of GreenWash shares along with a noise term which is normalised.

[8] In a real world setting the magnitude of these declines would not be known a priori and the exact nature of the relationship between the share prices would not be available. As such, to estimate the causal impact that the adverse ESG event had on the share price of GreenWash it is necessary to use an event study.