DOJ’s Ad Tech Antitrust Lawsuit: some comments on Google’s public response

On 24 January 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice (DoJ) formally charged Google with having monopolized the ad tech markets for publisher ad servers, ad exchanges and advertiser ad networks. On the same day, Google’s Vice President for Google Ads, Dan Taylor, responded with a press release entitled “DOJ’s lawsuit ignores the enormous competition in the online advertising industry”. This opinion piece comments on Google’s defense “sentence-by-sentence”.

Google’s press release of 24 January 2023

Google: “Today’s lawsuit from the Department of Justice attempts to pick winners and losers in the highly competitive advertising technology sector.”

Comment: The lawsuit does not pick a winner or loser. Its purpose is to obtain judicial clarify as to which anti-competitive practices a dominant company may not use to turn itself into a winner. It is Google’s search and online intermediation services that determine winners and losers billions of times a day, according to Google’s self-serving algorithms. That is why the DoJ’s action is important.

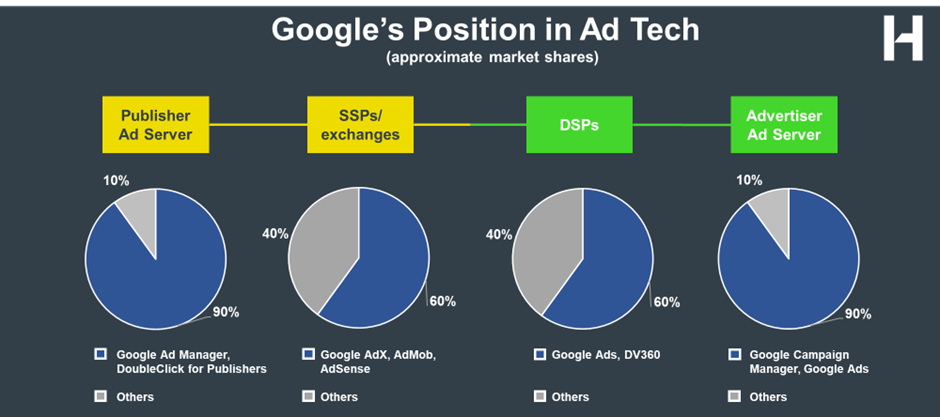

There is also no such thing as a “competitive advertising technology sector”. The case deals with the specific markets for the intermediation of non-searched based online advertising. According to all standards and previous investigations by various competition authorities, Google’s services clearly dominate each of those markets. For example, in the most recent sector inquiry into non-search based online advertising, the German Bundeskartellamt found in October 2022 that „Google has a leading position in all markets assessed. In particular on the markets for ad servers and SSP/AdExchanges, it is by far the most significant player […]. The other providers are generally significantly smaller or even very significantly weaker.“ Such unusual market concentration is the absolute opposite of a “highly competitive” market.

Graph 1) Google’s dominance across ad tech markets

Google: “It largely duplicates an unfounded lawsuit by the Texas Attorney General, much of which was recently dismissed by a federal court.”

Comment: Both arguments are unfounded. It is true that in 2020, several state attorney generals, led by Texas, filed an antitrust lawsuit with related allegations against Google’s ad tech practices. However, contrary to its press release, Google has not yet won dismissal of the claims relating to the DoJ case. In September 2022, the US District Court for the Southern District of New York only dismissed claims that are not included in the DoJ’s lawsuit. The central dismissal related to a controversial 2018 advertising deal with Meta, known as “Jedi Blue”. Google had considered this deal as “the centerpiece” of the Texas case. The DoJ’s lawsuit does not refer to that deal at all. None of the defining allegations that do overlap with the pending Texas complaint have been rejected by any judge. On the contrary, in the Texas case, the US District Court confirmed that several of the practices on which the DoJ now bases its lawsuit harm competition and/or are anti-competitive. Other practices have been raised in the DoJ lawsuit for the first time.

Moreover, some of the DoJ’s central allegations were already made in the French competition decision of 2021 relating to Google AdTech. Google did not appeal this decision, making it authoritative. It is not convincing for Google to claim now that the same allegations brought by the DoJ are unfounded. In any event, none of those points that matter to the DoJ case have been dismissed by a federal court.

|

DoJ Complaint January 2023 |

Texas Complaint Court Order September 2022 |

French Competition Authority 2021 |

|

Google’s restriction of Google Ads’ advertiser demand exclusively to AdX |

not addressed |

“Google Ads service buys exclusively or almost exclusively on AdX” |

|

Google’s restriction of effective real-time access to AdX exclusively to DFP |

not addressed |

“Lack of ‘real-time’ communication with third-party servers and contractual restrictions: |

|

Google’s limitation of dynamic allocation bidding techniques exclusively to AdX |

“The Court concludes that the States have plausibly alleged that Google’s use of Dynamic Allocation harmed competition in the ad-exchange market.” |

“SSPs integrated into DFP in the context of mediation are subject to significant disadvantages owing to their inability to bid for each impression.” |

|

Google’s providing AdX with a “last look” auction advantage over rival exchanges |

not addressed |

“SSPs integrated into DFP in the context of mediation are subject to significant disadvantages […]because of the right of last look enjoyed by AdX.” |

|

Google’s use of Project Bell, which lowered, without advertisers’ permission, bids to publishers who dared partner with Google’s competitors |

“The Court concludes that the complaint plausibly alleges that the Bell initiative was anticompetitive conduct causing harm to competition in the ad-server market.” |

not addressed |

|

Google’s deployment of sell-side Dynamic Revenue Share to manipulate auction bids—again, without publishers’ knowledge—to advantage AdX |

“The Complaint plausibly alleges that Google’s Dynamic Revenue Sharing harmed competition in the ad-exchange market.” |

“modalities of the dynamic revenue sharing feature have allowed Google to adjust its revenue share based on the offerings of competing SSP’s, to the detriment of publishers” |

|

Google’s use of Project Poirot to thwart the competitive threat of header bidding by secretly and artificially manipulating DV360’s advertiser bids on rival ad exchanges using header bidding in order to ensure transactions were won by Google’s AdX |

“The complaint plausibly alleges that Projects Poirot and Elmo were anticompetitive actions”

|

not addressed |

|

Google’s veiled introduction of so-called Unified Pricing Rules that took away publishers’ power to transact with rival ad exchanges at preferred prices |

“The complaint plausibly alleges that the use of uniform price floors was anticompetitive conduct in the market for ad exchanges and the markets for ad-buying tools used by small advertisers and large advertisers.” |

“The introduction of the unified first price auction and Unified Pricing Rules […] introduced additional barriers restricting in particular the ability of third-party SSPs to offset the advantages enjoyed by AdX.” |

|

Google’s AdX has sufficient market power in the market for ad exchanges for open web display advertising in the United States to coerce publishers to license DFP, thus restraining competition in the market for publisher ad servers for open web display advertising in the United States. |

“The States plausibly allege that Google used its monopoly power in AdX to actually coerce publishers into licensing a separate and distinct product, Google’s DFP ad server, and that Google’s actions had anticompetitive effects in both markets.”

|

not addressed |

Google: “DOJ is doubling down on a flawed argument that would slow innovation, raise advertising fees and make it harder for thousands of small businesses and publishers to grow.”

Comment: This allegation is not backed by anything. The DoJ – and several enforcement authorities before – lay down in detail that it is Google’s conduct across the ad tech stack that has led to less innovation, higher fees for advertisers and less revenue for thousands of small businesses and publishers. This, in turn, harmed billions of internet users who had less choice amongst publishers than in a competitive market and had to pay higher prices for advertising businesses than otherwise.

Google: “DOJ is demanding that we unwind two acquisitions that were reviewed by U.S. regulators 12 years ago (AdMeld) and 15 years ago (DoubleClick). In seeking to reverse these two acquisitions, DOJ is attempting to rewrite history at the expense of publishers, advertisers and internet users. Both of these acquisitions enabled us to invest heavily in developing new and innovative advertising technologies. These deals were reviewed by regulators, including by DOJ, and allowed to proceed. Since then, competition in this sector has only increased.

Comment: Google again turns the case on its head by claiming that it is the DoJ's position that harms publishers, advertisers and internet users. In addition, Google suggests that the enforcement authorities’ decisions to allow Google to acquire DoubleClick and AdMeld 12 and 15 years ago should now shield Google from antitrust enforcement against activities carried out by such entities. Yet, the DoJ’s lawsuit is not a revived merger review but a monopolization case challenging several closely interrelated unilateral conducts carried out by Google over some 15 years. Google’s original acquisitions were rightly identified as forming part of a much more comprehensive strategy to monopolize the markets for the intermediation of non-search-based advertising.

In its merger filings, Google had not laid out its future strategy. It even made promises to appease the authorities which it later did not keep (such as not to reduce third-party access to the DoubleClick ID). Faced with a massive information asymmetry, the authorities could not have possibly foreseen how the markets would develop and what impact the acquisitions would have more than ten years down the line, if paired with a particular set of anti-competitive conducts. If they had known the full picture, the acquisitions could never have been approved.

Moreover, back in 2008, the internet economy looked different – and was looked at differently. Antitrust authorities were not yet as conscious of the harm caused by cross-market dominance of digital conglomerates as they rightly are today. The authorities still pursued a traditional “market-by-market” analysis. They did not consider, for instance, how Google could use a dominant position in non-search-based advertising as a means to also affect competition in search-based advertising. Over the years, it became apparent that this “market-by-market” analysis was insufficient and that antitrust review requires a more comprehensive review of the entire ecosystem in which an acquisition takes place.

Further, while at the time of the acquisitions, publishers may still have relied on multiple intermediation platforms because competition still existed, market conditions have significantly changed over the years. What was acceptable back then is no longer acceptable.

Moreover, not the previous acquisitions as such but their combination with the unilateral conduct carried out afterwards led to the monopolization of ad tech markets. The fact alone that the authorities were blindfolded by Google some 15 years ago may not and should not justify any inactivity now. Google cannot possibly presume that a merger review based on incomplete facts and unkept promises shields its subsequent conduct from antitrust scrutiny.

Google: “We are one of hundreds of companies that enable the placement of ads across the Internet. And it’s been well reported that competition is increasing as more and more companies enter and invest in building their advertising businesses.”

Comment: The complaint is not about providing ad inventory, but about intermediation between publishers and advertisers for the placement of display ads. While there are several companies offering such services, Google clearly dominates the market. The survival of some rivals does not call Google’s dominance into question.

Google: “Last year, Microsoft acquired Xandr – an advertising platform that, like Google and many of its competitors, has a full ad tech stack that serves advertisers and publishers. This acquisition enabled Microsoft to sign a landmark deal to build Netflix’s advertising business. The government did not challenge this acquisition.”

Comment: The DoJ’s case is not about Microsoft, another tech giant, but about Google. For the reasons explained by the DoJ, other ad tech providers have significant competitive disadvantages due to Google’s anti-competitive conduct. The fact that thus far even the mighty tech giants Google itself refers to were unable to challenge Google’s market positions suggests that no company is so capable. Irrespectively, while Netflix’s video advertising business is relevant, that business does not involve real-time bidding in the open web that the DoJ case addresses. It is a well known strategy of Google to refer to developments in other markets to make those markets that it operates look competitive.

Google: “Amazon’s advertising business is now growing faster than Google and Meta’s advertising businesses.”

Comment: The DoJ case is about Google’s conduct on the markets for the intermediation of non-search-based advertising. These markets and Google’s conduct are unrelated to the direct sale of advertising space on one’s own websites. Amazon’s growing ad sales thanks to an increased interest in the new advertising category of retail media are unrelated to the DoJ case and cannot justify any illegal conduct Google is carrying out elsewhere.

Google: “Apple has a fast-growing advertising business, which is expected to reach over $30 billion in the next four years. It’s also been widely reported that Apple is building its own demand-side platform, expanding its advertising footprint.”

Comment: Apple’s growth in advertising sales with its walled garden is not a sign of competition in the open web, but is a result of Apple’s own anti-competitive conduct (namely Apple ATT and a revenue share agreement for search ads with Google). Whether Microsoft, Amazon or Apple succeed in leveraging their size to perform well in their respective ecosystems is unrelated to what Google does within the open web. Currently, those three giants do not offer a sufficient alternative for publishers and advertisers that require intermediation services for the programmatic sale and buying of ad inventory. It is a long-established lobbying strategy for Google to claim that it would compete with the other tech giants. At closer sight, however, these conglomerates neatly grow side-by-side and do not tend to attack each other in their respective core businesses.

Google: “Only five years after launching outside of mainland China, TikTok is reported to have nearly $10 billion in advertising revenue and continues to grow rapidly.”

Comment: Referring to TikTok’s links to China is another lobbying trick to divert attention from what matters, and to suggest that it requires a Google monopoly to counter alleged threats from China. In reality, TikTok plays no role in the ad tech stack. It sells ads independently on its social network and does not provide the intermediation services discussed in the DoJ’s lawsuit.

Google: “Media companies like Comcast and Disney, and retailers like Walmart and Target, continue to invest in building their own online advertising technology services.”

Comment: Those investments concern the direct sale of ad inventory of those companies. As in the case of TikTok, such direct sales by large publishers have nothing to do with the programmatic sale of ad inventory in the open web – which is what the DoJ case deals with.

Google: “There are also specialized advertising technology companies like AppLovin, Criteo, Index Exchange, Pubmatic, Magnite, MediaMath, OpenX, The Trade Desk, Unity and many others. In fact, The Trade Desk was recently ranked one of the fastest growing companies. These may not be household names, but they power many of the ads you see every day. With this increased competition, it’s no wonder fees across the industry are reportedly flat or falling for digital display advertising technology.”

Comment: The fact that some rivals still exist and/or even grow in some parts of the value chain does not preclude any monopolization or attempted monopolization. Google’s current market shares do not suggest that genuine competition exist. As Google explained when laying off 12.000 employees in January 2023, in 2022 and 2023 advertising prices did not fall due to more competition, but due to a global recession that reduces the ad spend of businesses.

Google: “This complaint mischaracterizes how our advertising technology products work. These products help publishers make money to fund their websites, apps and videos – which helps Internet users access a wide range of free content. And they make it easy for businesses to reach consumers through cost-effective digital advertising.”

Comment: The DoJ’s description of how the markets work are in line with several previous sector inquiries carried out by competition authorities around the globe. Google itself has consistently mischaracterized its technology and impact. The DoJ’s argument is that without Google’s anti-competitive conduct the advertising technology currently available would help publishers fund even more websites, apps and videos that internet users could choose from. The DoJ showed that but for Google’s conduct publishers would generate significantly higher revenues to fund content that they can then provide to internet users for free. Google tries to argue that without its intermediation services publishers would be worse off. But in reality, there are rivals, some of which Google’s press release mentions, that could provide the very same intermediation service to publishers – just better and at lower costs but for Google’s anti-competitive conduct.

Google: “Here are some facts: Our advertising technologies are built to work with our competitors' products. We make it easy for partners to choose the products and services they want to use across more than 80 rival platforms for publishers and over 700 rival platforms for advertisers.”

Comment: In line with previous expert reports, the DoJ explains in detail how Google has deployed several measures to reduce the interoperability between Google’s intermediation services and those of rivals. For instance, by granting its own intermediary a “last look” at the bids submitted via rival platforms, Google grants its own service the opportunity to easily outbid any other intermediary. Thus, while Google states that its technologies “are built to work with our competitors’ products”, they are in effect only doing that to the extent that it suits Google’s commercial interests. The products are designed and combined in a way to leverage Google’s dominance to the detriment of its respective competitors.

Google: “No one is forced to use our advertising technologies – they choose to use them because they’re effective.”

Comment: In theory, no one is forced to buy anything. Yet, if there is no real alternative, there is no genuine choice. If publishers and advertisers consider Google’s intermediation services as more effective, this is because Google’s anti-competitive conduct renders all rival intermediaries as less effective in comparison. Google’s services shine on the back of those that they suppress. There is nothing to suggest that rivals could not provide their services just as effectively if there was a level playing field.

Google: “In fact, publishers and advertisers typically work with multiple technologies simultaneously to reach customers and make more money. The average large publisher will use six different platforms to sell ads on its website this year, while advertisers and media agencies will use over three platforms to buy ads, on average.”

Comment: Several studies have shown that there is no genuine multi-homing, even amongst the “average large publisher” that Google’s press release picks out. Ad tech intermediation via real-time bidding, however, is much more relevant for smaller publishers and advertisers. Smaller publishers and advertisers in turn tend to single-home with Google’s “one-stop-shop” offerings. If anything, the existing level of multi-homing amongst larger companies demonstrates that businesses seek to escape the super-competitive fees that Google is charging. It is such multi-homing that Google seeks to prevent with various anti-competitive conducts listed by the DoJ.

Google: “Publishers who choose to use our advertising platforms keep the vast majority of the revenue our tools help facilitate. In total, we pay billions of dollars directly to the publishing partners in our ad network every year.”

Comment: Google does not deny that on average a whopping 30% of any advertising dollar earned by a publisher goes into Google’s pockets. This excessive take-out rate implies a lack of competition. The question is not how much money Google left publishers, but how much publishers should have received in the absence of Google’s conduct.

Google: “The current Administration has stressed the value of antitrust enforcement in reducing prices and expanding choice for the American people. We agree. But this lawsuit would have the opposite effect, making it harder for Google to offer efficient advertising tools that benefit publishers, advertisers and the wider U.S. economy. Antitrust cases shouldn’t penalize companies that offer popular, efficient services, particularly in difficult economic times.”

Comment: There is nothing to suggest that the DoJ’s case would render it harder for Google or anyone else to offer efficient advertising tools. By highlighting the relevance of intermediation tools for the U.S. economy, Google is highlighting the relevance of the antitrust enforcement in this case. Claiming that the case would penalize popular services, confuses the enforcement of the law with the penalization of success. The DoJ’s complaint aims at enhancing the efficiency of advertising tools that boost not just the U.S. economy. This is relevant, in particular in difficult economic times. It is Google’s conduct that makes it harder for everyone else and harms the economy, not the DoJ.

Google: “And they shouldn’t force companies to reverse 15-year-old investments that they have nurtured and worked hard to make successful, especially when those investments were already reviewed by regulators and allowed to proceed.”

Comment: The merger reviews 15 years ago, did not assess Google’s future investments and unilateral conduct that are now challenged by the DoJ. Neither does the DoJ’s case reverse any investment that was reviewed by regulators. It is the task of any enforcement authority to bring identified breaches of the law to an end.

Google: “We’ve spent years building and investing in our advertising technology business to support a vibrant, open web. We will vigorously contest attempts to break tools that are working for publishers, advertisers, and people across America.

Comment: Just because a company provides a tool that “works” does not justify its monopolizing the market for such tool. By claiming that the DoJ would “break” such tools, Google is taking recourse to one of its classical lobbying strategies: scaremongering. Yet, in this particular case, claiming disadvantages for internet users is even more far-fetched than in many previous Google campaigns. Not even a divestiture of Google’s ad tech stack would “break” anything, as the tools in questions would simply be provided by another company. Since such a company would finally be faced with undistorted competition, it would likely provide such tools more efficiently than Google currently does. The DoJ attempts to make all existing tools work better for the economy.

Putting Google’s lobbying in perspective

In an attachment to Google’s press release, entitled “Setting the record straight about our advertising technology business”, Google went so far as to claim “[t]he Department of Justice’s lawsuit puts at risk billions of dollars of value for publishers and advertisers, and useful ads and secure online experiences for consumers”. In other words, the DoJ was the bad guy harming society. In reality, the DoJ’s lawsuit only confirmed what the market has known and experienced for years. Each authority that looked at the ad tech sector more closely in recent years, came to similar conclusions and identified a lack of competition due to a bundle of unilateral conducts.

Overall, Google’s public defense thus follows the approach it has been pursuing around the globe for many years now in order to dismiss any regulatory intervention: (i) deny any wrongdoing, (ii) refer to other Big Tech firms to suggest competition, (iii) argue that the institution got it all wrong in lack of real market insights (iv) blame the institution for breaking the free internet, (v) divert attention to made-up risks of state intervention in order to (vi) influence the public opinion and (vi) instrumentalize Google’s user base to express criticism towards the institution that allegedly breaks their favorite toy. We have seen it all before.

The larger issue here is that Google is not just any company. Arguably, no other firm in history has ever had as strong an impact on what people believe and choose across the world than Google. Inter alia, via Android, Chrome, Google Search, YouTube, Gmail, Google Maps and Google News, Google influences several billion people every day. People were trained to trust Google’s algorithms. It should be a matter of course that with such power comes a particular responsibility to not distort facts and misrepresent enforcement activities of democratically legitimized authorities. Considering Google's inglorious track record for law infringements and fines in the billions, one may be inclined to say that once you have lost your reputation, you can do as you please. But, given the reach and relevance of the services provided by Google, there is far too much at stake to accept Google’s downplaying of its relevance, denying of its malpractices and blaming of law enforcement authorities for breaking the internet.

If we cannot even trust Google’s public press statements in such a high-profile case as this, how can we be expected to ever trust, for instance, any future AI-powered answering machines that Google trains behind the scenes in accordance with its own technical, ethical and legal views of the world? Can we really accept that Google is killing or gaining control over ever more independent media, while it demonstrates time and again that it does not (even) care much about state intervention? Running a business model that depends on trust, it should be in Google’s own interest to take investigations around the globe seriously and to react accordingly. To deny any wrongdoing and blame the authorities for breaking the internet will only call for more rigorous remedies.

In any event, Google’s misleading press release of 24 January 2022 in effect makes a stronger case for than against an antitrust intervention of the DoJ.

* Prof Dr Thomas Höppner is a partner, Dr Asja Zorn is an associate with Hausfeld. The authors advise companies adverse to Google, including in relation to Ad Tech.