1st Anniversary of the Digital Markets Act (DMA): Lessons learned and road ahead

The Digital Markets Act (DMA)[1] was introduced with the ambition of reshaping the regulatory landscape for Big Tech in the European Union (EU). It aims to make digital markets in the EU fairer and more contestable[2] through a regulatory ex ante approach. At the heart of the DMA are its substantive provisions in Art. 5 to 7. They contain a set of per se rules that impose do’s and don’ts on designated core platform services of gatekeepers. Most of these obligations became applicable a year ago, on March 7, 2024.[3]

The first anniversary of DMA enforcement provides an opportunity to reflect on the status of DMA enforcement and look at the road ahead. While much of the attention is currently on public enforcement, private enforcement of the DMA has the potential to play a vital role in the future of the regime.

Public enforcement: The EC’s role and challenges

The last year has been a busy one for the European Commission (EC), which has continued to designate gatekeepers, reviewed gatekeeper compliance reports, and initiated its first investigations for non-compliance with the DMA.[4] Below, we take a closer look at each of these three areas.

- Gatekeeper designations

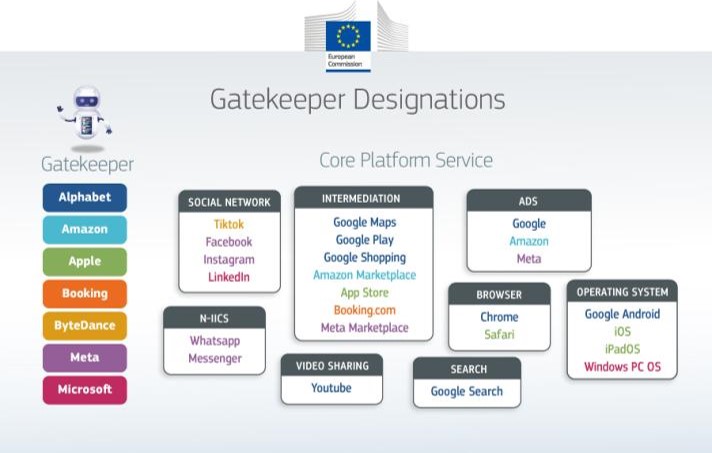

DMA obligations only apply to core platform services (CPS) of undertakings[5] that have been designated by the EC (so-called gatekeepers). The designation ultimately rests on qualitative criteria.[6] However, there are quantitative thresholds, which – if reached – trigger a rebuttable presumption that the qualitative criteria are met.[7] The EC designated the first six gatekeepers on September 6, 2023: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta and Microsoft.[8] The designations cover 22 CPS such as operating systems, online intermediation services, and online social networking services.[9] In May 2024, Booking.com was also designated as a gatekeeper for its online intermediation service, and Apple received a further gatekeeper designation in respect of iPadOS. ByteDance challenged the designation of TikTok as an online social networking service;[10] this challenge was, however, dismissed by the General Court (GC).[11] Not among the gatekeepers is X (formerly Twitter), which successfully rebutted the presumption in respect of both its online social networking service and its online advertising service.[12] Similarly, Microsoft successfully rebutted the presumption for its search engine, Bing,[13] its web browser, Edge,[14] and its online advertising service, Microsoft Advertising.[15] The decision not to designate Edge triggered Opera Norway to launch the first third-party appeal to the GC.[16] An overview of the status of the gatekeeper designation, setting out the seven gatekeepers and the 24 CPS is provided in the chart below:[17]

- Compliance reports

A gatekeeper’s obligations begin to apply six months after the designation decision.[18] In order to ensure transparency and allow the EC to monitor their DMA compliance, gatekeepers are required to submit compliance reports. According to Art. 11 (1) DMA, the gatekeeper has to describe in its report “in a detailed and transparent manner the measures it has implemented to ensure compliance with Art. 5, 6 and 7”.[19]

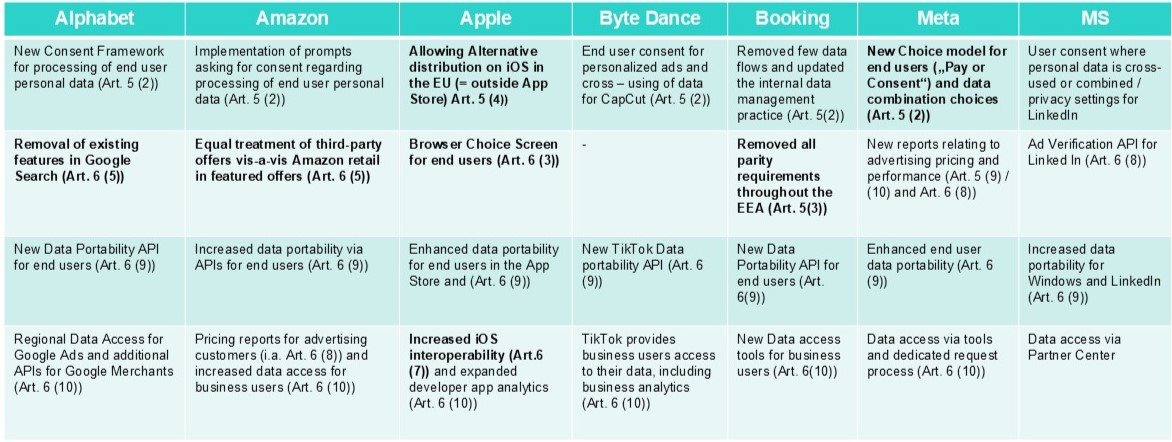

All seven gatekeepers have now published their first compliance reports.[20] These reports not only emphasize that the gatekeepers are fully DMA-compliant but also set out the changes they have made in order to implement the substantive DMA obligations. The below table contains a non-exhaustive overview of the compliance reports. Particularly relevant changes are highlighted in bold.

What the above table does not reveal is that the length, style and tone of the compliance reports diverge:

- Length: Alphabet (Google)[21] and Microsoft[22] submitted the most extensive reports, numbering 211 and 302 pages in length, respectively. Apple, in contrast, needed only 24 pages to report on its DMA compliance. While Alphabet possesses eight CPS and Apple only four, this does not explain the difference in length. For example, Microsoft had only two CPS and still submitted a much more comprehensive report. Apple’s brevity appears to be a conscious choice designed to send a message to the EC.

- Style: Gatekeepers also made different decisions when it comes to the presentational style of their compliance reports. Amazon’s and Booking.com’s reports were designed and structured as media-friendly, public relations documents. Conversely, Microsoft’s and ByteDance’s reports have the appearance of legal documents and are, in turn, more technical and with less emphasis on readability and presentation.

- Tone: Most remarkable are the differences in tone. Meta embraces the DMA: “When the first draft of the DMA was published in December 2020, Meta publicly welcomed the DMA’s ambitions. Meta’s commitment to compliance and implementing the DMA’s objectives has been resolute and steadfast ever since”.[23] In the same vein, Booking.com declares that “we make DMA compliance a priority”.[24] On the other end of the spectrum is Apple. Its compliance reports contain accusatory language, indicating, for instance, that the DMA requires changes that will bring harm to consumers and developers.[25]

As the subsequent EC investigations and the recent positioning of US gatekeepers under the Trump administration[26] have shown, the tone of compliance reports may not be informative. In fact, compliance reports were to a substantial extent window dressing. In many instances, small and seemingly insignificant implementations were portrayed as ground-breaking, bold approaches to DMA compliance. Other changes have been attributed to the DMA where they were, in fact, already obligatory (e.g. Booking.com’s removal of price parity clauses in the EEA was prompted by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruling[27] that such clauses are within the scope of the prohibition in Art. 101 (1) TFEU). Even when changes appear to fall short of the DMA’s compliance requirements, they were pictured as fully-compliant (e.g., as discussed below, Meta’s pay-or-consent model).

- Specification Proceedings and Non-Compliance Investigations

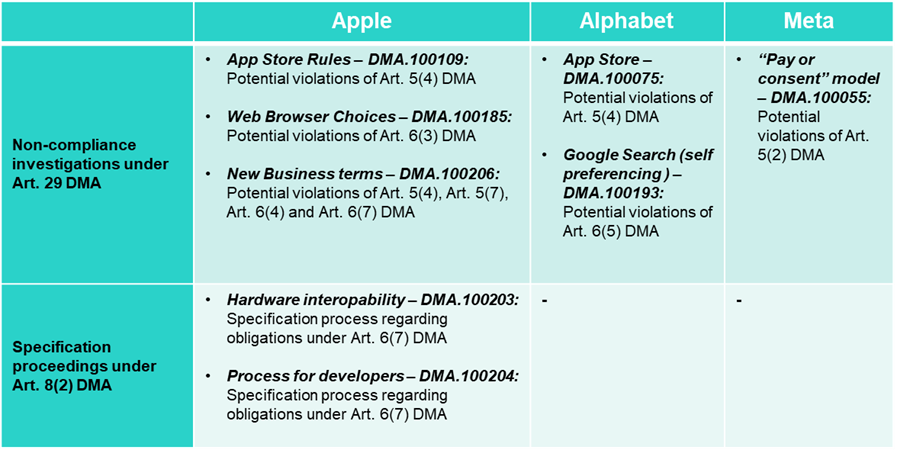

Less than twenty days after the compliance reports were submitted, the EC opened a series of non-compliance investigations under Art. 29 DMA on March 25, 2024.[28] In respect of Apple, the EC initiated a further non-compliance investigation in June 2024[29] and two specification proceedings under Art. 8 (2) in September 2024.[30] An overview of the EC’s proceedings is set out in the below table.

Apple in the spotlight

Apple is particularly affected, as three non-compliance proceedings under Art. 29 DMA and two specification proceedings under Art. 8 (2) DMA have been initiated against it.[31] The EC’s focus on Apple is not surprising, given the tone of its compliance reports, as well as accusations from 34 companies (including Spotify, Epic Games, and Deezer) that it is making a “mockery” of the DMA.[32]

Both initiated specification proceedings concern Apple’s interoperability obligations under Art. 6 (7) DMA. According to this provision, gatekeepers must grant software and hardware providers free and effective interoperability concerning their designated operating systems. On December 18, 2024, the EC published its preliminary findings and initiated a public consultation.[33] Firstly, in respect of interoperability with connected devices, the EC noted that numerous functionalities are available only for Apple hardware, such as Apple Watch and Apple AirPods, and proposed measures that Apple should extend these functionalities to third-party devices, including smartwatches and headphones.[34] Secondly, in respect of interoperability with iOS, the EC criticized Apple’s process of ensuring interoperability only by request (i.e. on a case-by-case basis) and not by design.[35] The EC proposed that the request process must be fair and transparent to ensure effective interoperability, with the proposed measures including, for example, providing information for developers, clear communication, support, timelines, a conciliation mechanism, and reporting on requests.[36]

The EC is also conducting three non-compliance investigations against Apple. With regard to Apple's App Store, the EC is assessing whether the fee structure for app developers, which is charged for “steering” end users to their own services, is compatible with Art. 5 (4) DMA.[37] Art. 5 (4) aims to prevent “anti-steering rules” by requiring gatekeepers to allow their business users (such as app developers) to steer consumers to offers outside the gatekeepers' platform, free of charge.[38] On June 24, 2024, the EC expressed the preliminary view that Apple’s business terms violate Art. 5(4) DMA, given that they do not allow developers to freely direct their customers by permitting only a limited number of ‘link-outs’ and charging acquisition fees beyond what is strictly necessary.[39]

In connection with Apple's App Store, the EC is also assessing whether Apple violates Art. 6 (4) DMA, which requires designated operating systems to allow "side-loading" of apps through third-party app stores.[40] In this regard, the EC is analyzing whether Apple imposes non-compliant restrictions on side-loading by requiring developers of third-party app stores and third-party apps to pay a ‘Core Technology Fee’ of €0.50 per installed app and creating numerous hurdles for side-loading.[41]

Finally, the EC is scrutinizing whether Apple violates Art. 6 (3) DMA, which requires that end users be able to easily uninstall any software applications on iOS and change default settings on iOS.[42]

Further investigations against Alphabet and Meta

In addition to the probes into Apple, the EC is also investigating Alphabet for possible violations of Art. 6 (5) DMA through self-preferencing, a practice well-known to antitrust jurisprudence,[43] with respect to their own vertical search services - such as Google Shopping, Google Hotels, and Google Flights - over rival services.[44] Additionally, the EC is investigating potential infringements of Art. 5 (4) DMA by Alphabet in its Play Store, particularly due to its initial acquisition fees and significant restrictions on ‘link-outs’ from the app.[45]

In respect of Meta, the EC is looking into its ‘pay-or-consent’-model in relation to the processing and combination of end users’ personal data, as it may not constitute “a less personalised, but equivalent alternative” within the meaning of Art. 5 (2) in conjunction with Recital 36 DMA.[46] On July 1, 2024, the EC sent its preliminary findings to Meta expressing the view that the ‘pay-or-consent’-model is non-compliant with the DMA, as it fails to meet the necessary requirements set out in Art. 5 (2) DMA.

No investigations yet against Amazon, Microsoft, Booking and ByteDance

So far, the EC has not launched any investigations against Amazon, Microsoft, ByteDance or Booking.com. However, the EC is informally assessing whether Amazon is self-preferencing its own branded products on the Amazon Store in violation of Art. 6 (5) DMA.[47] Additionally, the EC is currently pursuing an Art. 102 TFEU case against Microsoft in respect of potentially abusive tying practices related to Microsoft Teams.[48]

The absence of formal DMA investigations against these gatekeepers does not mean, however, that they have necessarily been deemed compliant. The EC's scarce resources and the need to set enforcement priorities are meaningful limits on its ability to investigate, and allegations of non-compliance have been made as to certain of these gatekeepers by third parties. For example, the European consumer organization BEUC has complained about the non-compliance of Microsoft, Amazon and Byte Dance.[49] Similarly, Hotrec – the Association of Hotels, Restaurants & Cafés in Europe – claimed in a press release that Booking.com remains non-compliant with the DMA after publishing its compliance report.[50]

Private Enforcement: Potential and advantages

Private enforcement is still at an early stage, and it remains to be seen what impact it will have in practice. Given its manifold advantages and the concerns about DMA underenforcement, it has the potential to play a vital role. While few private actions have been initiated to date, this may change in the future. If public enforcement is perceived to be slow or selective, we can expect to see an increase in private litigation. Once initial regulatory decisions set precedents, follow-on litigation is also likely to surge. The following section provides an overview of private enforcement mechanisms under the DMA.

- Role and Advantages of private enforcement

It is now generally accepted that private enforcement of the DMA is possible.[51] Art. 39 (1) DMA sets out the cooperation of national courts with the EC in “proceedings for the application” of the DMA and clarifies in Art. 39 (5) that national courts shall not issue decisions contrary to a decision by the EC. This implies that substantive DMA obligations can also be enforced under private law. Additionally, collective redress in civil courts is possible according to Art. 42 DMA, which refers to representative actions under Directive (EU) 2020/1828.[52]

Private enforcement should play a vital role and serve as the second pillar in ensuring compliance with the new DMA obligations, as it possesses substantial advantages. Firstly, it is well-suited to reduce the burden on the EC, which may lack the capacity to thoroughly investigate all potential infractions. Secondly, private enforcement allows for swift relief through preliminary injunctions. Thirdly, it provides an additional (plaintiff's) perspective and brings more voices to the table, e.g. business users such as publishers or advertisers as well as competitors of big tech. In the public enforcement context, those voices are sidelined to providing only commentary. Through this perspective, the enforcement of the DMA can be decentralized, thereby promoting a more balanced consideration of interests. As gatekeepers continue to challenge regulatory interpretations, private enforcement mechanisms provide an additional layer of scrutiny. Finally, in private enforcement actions, it is also possible to claim damages which serves as an additional deterrent against non-compliance.

- Interplay between public and private enforcement

With a view to the DMA's objective of preventing fragmentation of the internal market[53] and considering the position of the EC as the sole public enforcer, doubts have been raised as to whether private enforcement is only permissible when the plaintiff has first sought and obtained a decision from the EC.[54] These doubts are based on the DB Station ruling of the ECJ, in which the court decided that plaintiffs must first seek a decision from the national regulatory authority relating to railway infrastructure charges (Directive 2001/14/EC) before a civil court can rule on reimbursement claims based on Art. 102 TFEU.[55] The ECJ ruling concerned EU regulatory law and could therefore arguably be read across to apply to the DMA as a sector-specific regulation. This would effectively bar stand-alone actions.

However, there are compelling arguments pointing to the contrary conclusion. Under Directive 2001/14/EC, the relevant regulatory bodies of the Member States had exclusive competence to review railway charges, and civil courts were required to respect this. The DMA, however, operates under a different system, set out in Art. 39 DMA. Art. 39 DMA incorporates well-known antitrust mechanisms, derived from Art. 15 and 16 Regulation 1/2003, which do not mandate prior complaints to the EC. National courts are empowered to seek information or guidance from the EC regarding the application of the DMA, ensuring a cohesive and informed approach across jurisdictions. The EC is entitled to receive a written copy of the judgments issued by national courts that apply the DMA, facilitating an ongoing dialogue between national courts and the EC. Furthermore, the EC has the possibility of participating as an amicus curiae. In addition, the EC can request information from national courts when necessary to ensure consistency in enforcement. Therefore, national courts are only limited by the requirement, in Art. 39 (5) DMA, not to give a decision which runs counter to a decision adopted by the EC under the DMA. Unlike the regime of Directive 2001/14/EC, the EC has under DMA rules no exclusive competence to review DMA compliance and, thus, the DB Station ruling, according to which plaintiffs need to approach the regulator prior to launching a private enforcement action, does not apply to the DMA.

- Implementation of private enforcement in national law

Germany was the first EU Member State to implement private enforcement of infringements of Art. 5 to 7 DMA into its national law, through amendments to Section 33 et seq. of its Act against Restraints of Competition (‘ARC’).[56] The rules for DMA claims largely follow those for private enforcement of antitrust cases, which have, in turn, been based on the Damages Directive.[57] Under the revised ARC, affected parties can seek cease-and-desist orders (including preliminary injunctions in urgent cases) and injured parties can bring damage claims in the form of stand-alone and follow-on actions. Plaintiffs enjoy many benefits, such as res judicata effect of final and binding EC decisions, including designation decisions,; extended statute of limitation rules; and the ability to make applications for disclosure. Moreover, the specialized chambers responsible for antitrust damages cases will also hear DMA claims. This should help to accelerate proceedings as these chambers possess subject matter expertise, are able to handle complex cases, and often already have experience working on cases involving digital markets.[58]

Most of the EU Member States have, however, not (yet) implemented specific provisions on private enforcement of the DMA into their national laws.[59] This does not necessarily mean that claims cannot be brought in those Member States, as the plaintiff can either rely on general tort provisions or on the direct effect of the DMA. For example, in the Netherlands, where private enforcement of the DMA has not been specifically implemented, requests for cease-and-desist orders and claims for damages can be based on the general tort provisions set out in the Dutch Civil Code.[60] Under Dutch tort law, an infringement of a directly applicable provision of EU law is considered an unlawful act. This is the case for Art. 5 and 6 DMA.[61]

- Selected Substantive and Procedural Issues

Given the novelty of the DMA, private enforcement will raise numerous procedural and substantive issues. Four of these are discussed below.

Burden of proof for the infringement

The burden of proof is often a material factor in determining the outcome of litigation, and private enforcement actions are no exception. In stand-alone antitrust cases, the burden of proof concerning the infringement is typically on the plaintiff. However, this may not be the case for DMA claims. The DMA states in Art. 8 (1) DMA that “the gatekeeper shall ensure and demonstrate compliance with the obligations laid down in Articles 5, 6 and 7 of this Regulation.” This is commonly referred to as the accountability principle and means that it is incumbent on the gatekeeper to prove its compliance.

While some commentators suggest that the principle of accountability should be limited to public enforcement and that, in private enforcement, plaintiffs should bear the burden of proving an infringement, numerous arguments suggest that this is not the case. First, the wording of Art. 8 (1) DMA does not differentiate between public and private enforcement. Arguably, the same standard should apply to both. Second, if the gatekeepers carry the burden of proof in public enforcement, where they may face substantial fines under Art. 29 to 31 DMA, then they should also carry it in civil proceedings.[62] Finally, the interpretation of this issue under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR),[63] to which the DMA frequently refers,[64] also suggest that the burden of proof is on the gatekeeper. The ECJ has ruled that the accountability principle under the GDPR[65] (which mirrors the DMA accountability principle in Art. 8 (1) DMA) constitutes ‘a rule of general application’ and accordingly also applies to private damages claims as it.[66]

Damages – injury sustained and quantum

Most jurisdictions distinguish in damages action between ‘injury sustained’ and ‘quantum’. Injury sustained means that the infringement must have caused harm to the plaintiff. The harm does not need to be quantified at this stage; occurrence of any causal harm suffices. If such causal harm is demonstrated, the harm will need to be quantified. In this second ‘quantum’ stage, the standard of proof is often relaxed.

The burden of proof concerning injury sustained typically rests on the plaintiff. This hurdle can be a high one as a counterfactual will need to be established.[67] Unlike under Art. 17 (2) Damages Directive and Section 33a(2) ARC, which establishes a rebuttable presumption of harm for cartel infringement, there is neither a statutory presumption of harm in the German ARC nor in the legal systems of other Member States for DMA violations (so far).[68] However, in the absence of a statutory presumption, it is possible that civil courts will establish a prima facie presumption for DMA claims. For example, the German Federal Court of Justice (FCJ)[69] introduced such a presumption for follow-on damages cases in respect of cartel infringements.[70] The FCJ has extended the scope of the presumption in subsequent cases, e.g. it ruled[71] that it also applies to per se impermissible exchange of price information. It may well be that the presumption will also be extended to DMA infringements as gatekeepers possess substantial market power and, accordingly, infringements are likely to cause anti-competitive effects. Moreover, the principle of effectiveness may call for such an interpretation as without a prima facie presumption it may prove difficult for plaintiffs to successfully seek compensation for DMA infringements.

Quantum is a major battleground in many follow-on damages cases based on antitrust violations and it is likely that the same will be true for claims under the DMA. While the burden of proof for quantum rests on plaintiffs, many EU Member States have procedural rules in place that relax the standard of proof. This can be seen in Germany, which permits courts to estimate damages with or without the assistance of a court appointed expert.[72] Particularly relevant for DMA damages claims could also be that it is possible to take gatekeeper’s profits into account for the quantification of damages.[73] Nevertheless, as with antitrust damages claims, economic experts will likely play a vital role for quantification of DMA claims.

Jurisdiction

Many battles will likely be fought over jurisdiction. This is particularly likely where the parent companies of the gatekeepers are not domiciled in the EU. However, for their EU subsidiaries, which most gatekeepers possess, jurisdiction can be established at their domicile. The DMA defines “undertakings” under Art. 2 (27) DMA broadly, which refers to the gatekeeper’s entire group, and the designation decisions are explicitly addressed to the gatekeeper’s group entity (as opposed to only the ultimate parent company). Accordingly, cases can be brought under Art. 8 (1) of the Brussels Ia Regulation[74] against the EU subsidiaries of gatekeepers in their country of domicile. There, courts have general jurisdiction and therefore unlimited power to issue orders or award damages.

An alternative could be to rely on the tort gateway to jurisdiction under Art. 7 (2) of the Brussels Ia Regulation. According to this provision, actions can be brought where the harmful event occurred (forum delicti). This can be either the place where the wrongful act was committed or the place where the damage took place. Given its proximity to competition law, it is likely[75] that courts will apply competition law jurisprudence to DMA infringements. Accordingly, it is arguably that plaintiffs can claim in a jurisdiction for either the entirety of the damages suffered or only for the damage that occurred in the jurisdiction. This latter type of territorially limited jurisdiction for damages is known as the mosaic principle. In CDC Hydrogen Peroxide, the ECJ held that, in cartel follow-on damages cases, the jurisdiction of the seat of the victim can rule upon the entirety of the damage claimed and, thus, is not limited to claims for only the damages sustained in the jurisdiction (in other words, the mosaic principle does not apply). However, ECJ case law is evolving[76] and, accordingly, uncertainties remain.

Procedural delays

In antitrust private enforcement cases, tactics to prolong litigation are commonplace. Defendants often raise numerous objections that increase complexity and thereby make the case more complicated to litigate and adjudicate. In addition, defendants will regularly file motions to stay the proceedings and/or request a referral to the ECJ, preventing the case from progressing. Needless to say, it is expected that defendants will act similarly in respect of DMA claims in order to avoid early judgments. The DMA, however, leaves less room for such tactics. Its design around per se rules means that, unlike claims for abuse of dominance, infringements of the DMA’s substantive provision in Art. 5 to 7 do not require the establishment of a dominant position nor of anti-competitive effects, and it is also not possible to raise business justifications as a defence.[77] However, procedural tactics remain an option. If civil courts embrace the concept of urgency in the DMA – which seems to rest on the notion that infringement must be stopped at once – they will reject any unreasonable procedural requests which aim to prolong litigation.

Conclusion

The results of the first year of public DMA enforcement are mixed. It became clear that the DMA is not self-executing, whereby gatekeepers would fully comply and the EC’s role would be limited to monitoring. Instead, the gatekeepers made some changes and, when these were deemed insufficient, the EC has had to intervene and open non-compliance proceedings. However, despite multiple non-compliance accusations against Microsoft, Amazon, Byte Dance or Booking, the EC has yet to launch investigations.[78] This creates concerns about underenforcement that will likely remain a concern in the foreseeable future. The EC’s resources appear too limited to effectively master its role as sole enforcer and swiftly intervene against non-compliance. Moreover, it stands to reason that gatekeepers like Apple, Meta, and Google may seek to challenge any EC decisions. If they appeal decisions of the EC to the European courts, they may turn disputes into full-blown fights that could tax the EC’s resources. As a consequence, the EC’s ability to bring new cases could be curtailed and it will have to prioritize even further. Finally, the recent pushback from the Trump administration,[79] which has contended that the DMA discriminates against U.S. companies, is protectionist, and was formed as part of an EU effort to subsidize, might have a chilling effect on public enforcement.[80] While the EC is publicly denying[81] that it will give in to threats from the United States, it may avoid open confrontation with non-compliant gatekeepers for political reasons.

Given these challenges, it is widely expected that private enforcement will play an important role.[82] While private enforcement is currently still in its early stages, it has many advantages and may prove crucial for the effective enforcement of the DMA. Germany is particularly likely to become an important forum for DMA claims as it has already implemented private enforcement of the DMA in its national law and provides many benefits for plaintiffs. In the next few years, we would expect primarily stand-alone litigation, in particular fast-track proceedings where plaintiffs request preliminary injunctions. Once there are sufficient final and binding non-compliance decisions, follow-on litigation will likely pick up.

*Dr. Ann-Christin Richter is the Managing Partner for Germany and Dr. René Galle is a Partner in Hamburg. The authors would like to thank Fabian Kieß for his invaluable support in putting together this article.

Footnotes

[1] Regulation (EU) 2022/1925, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2022/1925/oj/eng.

[2] See: Art. 1 (1) DMA.

[3] Exceptions are Art. 7 (2) (b) and (c) DMA.

[4] To date (7 March 2025), the EC has adopted 47 decisions, see https://digital-markets-act-cases.ec.europa.eu/search. Most relate to the designation process.

[5] An “undertaking” means, according to Art. 2 (27) DMA, “an entity engaged in an economic activity, regardless of its legal status and the way in which it is financed, including all linked enterprises or connected undertakings that form a group through the direct or indirect control of one enterprise or undertaking by another”.

[6] See: Art 3 (1) DMA.

[7] See: Art. 3 (2) DMA.

[8] EC press release: Digital Markets Act: Commission designates six gatekeepers, September 6, 2023.

[9] The CPS covered by the DMA are exhaustively defined in Art. 2 (2) DMA.

[10] For online networking services, the stricter obligations set out in Art. 6 (12) DMA apply.

[11] GC, Judgment of July 17, 2024 – T-1077/23 – ByteDance.

[12] EC, Decision of May 13, 2024, DMA.10032 – X – online advertising services; EC, press release https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/commission-concludes-online-social-networking-service-x-should-not-be-designated-under-digital-2024-10-16_en.

[13] EC, Decision of February 12, 2024, DMA.100015 – Microsoft – online search engines.

[14] EC, Decision of February 12, 2024, DMA.100028 – Microsoft – web browsers.

[15] EC, Decision of February 12, 2024, DMA.10034 – Microsoft – online advertising services.

[16] GC, T-357/24 – Opera Norway v Commission.

[17] https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/gatekeepers_en.

[18] Art. 3 (10) DMA.

[19] Art. 11 (1) DMA.

[20] The reports can be found at https://digital-markets-act-cases.ec.europa.eu/reports/compliance-reports.

[21] Alphabet, EU Digital Markets Act (EU DMA) Compliance Report, Non-Confidential Summary, March 7, 2024, NCV of Compliance Report 2025.

[22] Microsoft, Microsoft DMA Compliance Report, 2024, Microsoft’s Compliance with Digital Markets Act.

[23] Meta, Meta’s Compliance with the Digital Markets Act, March 6, 2024, Meta DMA Compliance Report - Non-confidential Summary.docx, p. 2.

[24] Booking, Booking Holdings Inc.’s Digital Markets Act Compliance Report, November, 2024, https://www.bookingholdings.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/DMA-Compliance-Report.pdf, p. 2.

[25] Apple, Apple’s Non-Confidential Summary of DMA Compliance Report, March 7, 2024, p. 1: “The DMA requires changes to this system that bring greater risks to users and developers. This includes new avenues for malware, fraud and scams, illicit and harmful content, and other privacy and security threats. These changes also compromise Apple’s ability to detect, prevent, and take action against malicious apps on iOS and to support users impacted by issues with apps downloaded outside of the App Store.”

[26] See President Trumps speech on the World Economic Forum in Davos: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/23/us/politics/trump-davos-europe-tariffs.html. See also the letter from 23 February, 2025 from the Judicial Committee from the U.S. House of Representatives: https://judiciary.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/republicans-judiciary.house.gov/files/evo-media-document/2025-02-23%20JDJ%20SF%20to%20Ribera%20re%20DMA.pdf.

[27] ECJ, Judgment of September 19, 2024 – C-264/23 – Booking.com.

[28] EC, press release: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_1689, March 25, 2024.

[29] EC, Decision of June 24, 2024, DMA.10026 – Apple new business terms.

[30] EC, press release: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_4761, September 19, 2024.

[31] In principle, it is at the discretion of the EC whether to initiate a specification procedure based on Art. 8 (2) DMA or a non-compliance procedure under Art. 29 DMA in the event of potential infringements of the obligations outlined in Art. 6 and 7 DMA. Art. 8 (4) DMA clarifies that specification Proceedings pursuant to Art. 8 (2) DMA are without prejudice to the powers of the EC under Art. 29, 30, and 31 DMA.

[32] The open letter can be found at: A Letter to the European Commission on Apple's Lack of DMA Compliance — Spotify.

[33] EC, press release: https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/commission-seeks-feedback-measures-apple-should-take-ensure-interoperability-under-digital-markets-2024-12-19_en, December 19, 2024.

[34] See EC, Case summary of December 19, 2024, DMA.100203, p. 1 et seq. – Apple – iOS – SP Features for connected physical devices.

[35] EC, Case summary of December 19, 2024, DMA.100204, p. 1 – Apple – iOS and IPadOS – SP Process.

[36] EC, Case summary of December 19, 2024, DMA.100204, p. 1 et seq. – Apple – iOS and IPadOS – SP Process.

[37] EC, press release: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_3433, June 24, 2024.

[38] A prominent Art. 102 TFEU case is the EC's €1.8 billion fine against Apple, for imposing restrictions on app developers that prevented them from informing iOS users about alternative, cheaper music subscription options. See EC, press release: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_1161, March 4, 2024.

[39] EC, Decision of March 25, 2024, DMA.100109, para 9 et seq. – Apple – Online Intermediation Services – app stores – App Store – Article 5 (4).

[40] EC, Decision of June 24, 2024, DMA.100206 – Apple new business terms.

[41] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_3433, June 24, 2024.

[42] EC, Decision of March 25, 2024, DMA.100109 – Apple – Operating systems – iOS – Article 6(3).

[43] See e.g., ECJ, Judgment of September 10, 2024 – C-48/22 P – Google Shopping.

[44] EC, Decision of March 25, 2024, DMA.100103 – Alphabet – Online Search Engine – Google Search.

[45] EC, Decision of March 25, 2024, DMA.100075 – Alphabet – Online Intermediation Services – app stores – Google Play – Article 5(4).

[46] EC, Decision of March 25, 2024, DMA.10055 – Meta – Article 5(2).

[47] EC, press release: https://digital-markets-act.ec.europa.eu/commission-opens-non-compliance-investigations-against-alphabet-apple-and-meta-under-digital-markets-2024-03-25_en.

[48] EC, press release: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_3446.

[49] See BEUC, Implementation by Meta, Apple, Google, Amazon, ByteDance and Microsoft of their obligations under the Digital Markets Act, September 2, 2024, https://www.beuc.eu/sites/default/files/publications/BEUC-X-2024-062_Summary-non-compliance-reports-gatekeepers.pdf.

[50] See Hotrec, press release: hotrec-press-release-booking.com-remains-non-compliant-with-digital-markets-act.pdf, November 14, 2024.

[51] See Galle/Dressel, EuZW 2024, 107 with further references; Haus/Steinseifer, ZWeR 2023, 105, 118.

[52] See Richter/Apell, Private Enforcement of the Digital Markets Act: What to expect under German law, Competition Bulletin, May 16, 2024, https://www.hausfeld.com/de-de/was-wir-denken/competition-bulletin/private-enforcement-of-the-digital-markets-act-what-to-expect-under-german-law/.

[53] See for example Recital 9 and Art. 1 (5) DMA.

[54] See Elkerbout/Merenlahti, Looking ahead at private enforcement of the DMA and why the DB Station Judgment does not hinder standalone damages claims, January 31, 2024, available at https://theplatformlaw.blog/2025/01/31/looking-ahead-at-private-enforcement-of-the-dma-and-why-the-db-station-judgment-does-not-hinder-standalone-damages-claims/.

[55] ECJ, Judgment of October 27, 2022, C-721/20, para. 81 et seq. – DB Station.

[56] See the FCO’s press release: Bundeskartellamt - Homepage - Amendment to the German Competition Act (Gesetz gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen – GWB; 11th amendment to the GWB).

[57] Directive 2014/104/EU.

[58] See Richter/Apell, Private Enforcement of the Digital Markets Act: What to expect under German law, Competition Bulletin, May 16, 2024, https://www.hausfeld.com/de-de/was-wir-denken/competition-bulletin/private-enforcement-of-the-digital-markets-act-what-to-expect-under-german-law.

[59] For an overview of the status of DMA implementation as of June 2024, see Alba Ribera Martínez, The Decentralisation of the DMA's Enforcement System - Kluwer Competition Law Blog

[60] See Cornelissen/van Uden, in: Schmidt/Hübener, New Digital Markets, 2023, para. 210 et seq.

[61] Cornelissen/van Uden, in: Schmidt/Hübener, New Digital Markets, 2023, para. 215 et seq.

[62] This argument is closely related to the general notion that the burden of proof in criminal cases is higher than in civil cases. While the imposition of fines under EU law is strictly speaking not a matter of criminal law, there is a criminal law aspect to it. See: ECJ, Judgment of September 14, 2023, C-27/22, para 48 et seq. – Volkswagen Group Italia).

[63] Regulation (EU) 2016/679.

[64] See e.g. Art. 5 (2) and (8), Art. 8 (1), Art. 13 (5) and Art. 36 (3).

[65] See Art. 5 (2) and 24 (1) GDPR. Art. 5 (2) reads ”The controller shall be responsible for, and be able to demonstrate compliance with, paragraph 1 (‘accountability’)”. Art. 24 (1) reads ”Taking into account the nature, scope, context and purposes of processing as well as the risks of varying likelihood and severity for the rights and freedoms of natural persons, the controller shall implement appropriate technical and organisational measures to ensure and to be able to demonstrate that processing is performed in accordance with this Regulation”.

[66] ECJ, Judgment of December 14, 2023, C-340/21, para. 52 et seq. – Natsionalna agentsia za prihodite.

[67] See Richter/Gömann NZKart 2023, 208, 212.

[68] Richter/Apell, Private Enforcement of the Digital Markets Act: What to expect under German law, Competition Bulletin, May 16, 2024, https://www.hausfeld.com/de-de/was-wir-denken/competition-bulletin/private-enforcement-of-the-digital-markets-act-what-to-expect-under-german-law/.

[69] German Federal Supreme Court, judgment from 11.12.2018, KZR 26/17, WuW 2019, 91, Rec. 55 – Schienenkartell.

[70] The statutory presumption of Art. 17 (2) Damages Directive and Section 33a (2) ARC were not applicable under temporal law (the cartel infringements took place before both became applicable).

[71] German Federal Supreme Court, judgment from 29.11.2022, KZR 42/20, WuW 2023, 99 Rec. 45 ff. – Schlecker.

[72] Section 287 of the German Civil Procedure Code. See further: Richter/Apell, Private Enforcement of the Digital Markets Act: What to expect under German law, Competition Bulletin, May 16, 2024, https://www.hausfeld.com/de-de/was-wir-denken/competition-bulletin/private-enforcement-of-the-digital-markets-act-what-to-expect-under-german-law/#_ftn3

[73] See Sect. 33(a) (3) S. 2 ARC.

[74] Regulation (EU) No 1215/2012.

[75] Komninos, Private Enforcement of the DMA Rules before the National Courts, April 5, 2024, 11.

[76] See e.g. ECJ, judgment of July 5, 2018, Rec. 43 – FlyLaL-Lithuanian Airlines; ECJ, judgment of July 29, 2019, C-451/18, ECLI:EU:C:2019:635, WuW 2019, 462 – Tibor-Trans; ECJ, judgment of September 3, 2021, C-30/20, ECLI:EU:C:2021:604, WuW 2021, 515, Rec. 20, 40 ff. – Volvo; ECJ, judgment of November 24, 2020, C-59/19, ECLI:EU:C:2020:950, WuW 2021, 31 – Wikingerhof.

[77] Art. 5 to 7 DMA do not allow for a general business justification. Instead, they contain very narrow exceptions to the obligation. For example, the interoperability obligation of Art. 6 (4) allows the gatekeeper to impose strictly necessary and proportionate measures to ensure that third-party software applications or software application stores do not endanger the integrity of the hardware or operating system.[78] E.g. the European Consumer Organization’s analysis of non-compliance, BEUC-X-2024-062_Summary-non-compliance-reports-gatekeepers.pdf or Hotrec’s press release on the incompliance of Booking.com, Booking.com remains non-compliant with the Digital Markets Act | HOTREC – European Hospitality.

[79] See President Trumps speech on the World Economic Forum in Davos: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/23/us/politics/trump-davos-europe-tariffs.html. See also the letter of February 23, 2025, from the Judicial Committee from the U.S. House of Representatives: https://judiciary.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/republicans-judiciary.house.gov/files/evo-media-document/2025-02-23%20JDJ%20SF%20to%20Ribera%20re%20DMA.pdf.

[80] See President Trumps speech on the World Economic Forum in Davos: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/23/us/politics/trump-davos-europe-tariffs.html. See also the letter of February 23, 2025, from the Judicial Committee from the U.S. House of Representatives: https://judiciary.house.gov/sites/evo-subsites/republicans-judiciary.house.gov/files/evo-media-document/2025-02-23%20JDJ%20SF%20to%20Ribera%20re%20DMA.pdf.

[81] EU Lawmakers Push Back on U.S. Criticism of Tech Antitrust Regulation - WSJ.

[82] See Richter/Apell, Private Enforcement of the Digital Markets Act: What to expect under German law, Competition Bulletin, May 16, 2024, Hausfeld | Private enforcement of the Digital Markets Act: What to expect under German law.