Facts of the case

The judgments concern the legitimacy of a cooperation between Google and the Federal Republic of Germany regarding the preferential display within general search results pages of content published by a health portal operated by the German Ministry of Health (“GMH”).

In September 2020, the GMH launched the website gesund.bund.de, a “national health portal” with the declared objective of providing quality-based, independent and easily understandable health information online. The portal publishes articles, graphs, images, and videos about diseases and health-related topics.

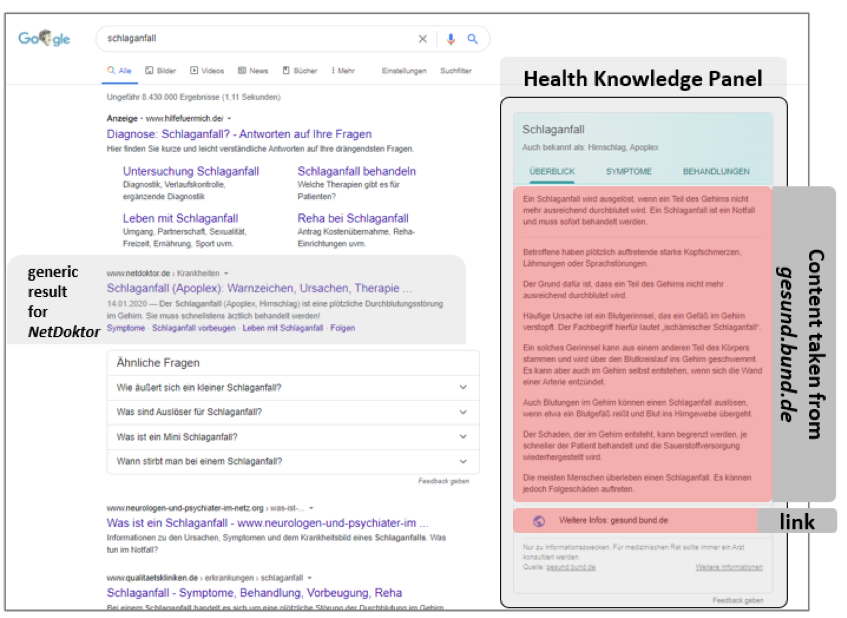

In October 2020, in a joint press conference, Google and the GMH announced the start of a cooperation for search queries entered on Google Search that relate to health topics.[2] The cooperation entailed that whenever a user enters a keyword that corresponds to a pre-determined list of diseases, Google shall exclusively display content published on gesund.bund.de about such disease in a prominently displayed separate info box, called the “Health Knowledge Panel”. At the bottom of such boxes, there is a link that, if clicked, leads the user to the website gesund.bund.de.

The German Minister of Health declared: “Whoever googles health, shall land on our portal and find the required information there. Gesund.bund.de shall become the central port of call for reliable health information online. What is more obvious than to directly cooperate with Germany’s most popular search engine, namely Google? In the future, in return of a medical search query, responses of [gesund.bund.de] will be presented there in a prominent, highlighted info box. […] I am certain that the cooperation with Google means a significant boost in public awareness for [gesund.bund.de] and that the cooperation will ensure that the portal will become one of the most relevant points of contact for citizens online for health information.”

Referring to the fact that in lack of relevant content, prior to the cooperation gesund.bund.de had not appeared within the first search results pages on Google, the Minister added: “If we have an interest in bringing across objective, sound and evidence-based information, it is no use for me, if we appear on slot 783,000 on Google.” The Health Knowledge Panel is shown below:

Established in 1999, the plaintiff NetDoktor is the leading online health portal in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Based upon scientific standards, doctors explain all relevant medical topics on diseases, symptoms, medication, methods for treatments, etc., in order to empower users to enter into sophisticated dialogues with their doctors. Due to NetDoktor’s significant investment in editorial quality, for the majority of health-related search terms, the portal had consistently ranked amongst the first of Google’s relevance-based generic (organic) search results, often as the top result.

Following Google’s display of the Health Knowledge Panels with content from gesund.bund.de, NetDoktor continued to rank high within generic search results. However, due to the large real estate that the Health Knowledge Panels occupy, NetDoktor lost visibility, in particular on mobile devices. As a result, within days, the percentage of users ultimately clicking on the search results leading to NetDoktor, the so called click-through-rate on Google Search, dropped significantly – as much as 37% for the most relevant diseases.

On November 26th, 2020, NetDoktor filed actions seeking injunctions against both Google and the Federal Republic of Germany represented by the GMH. NetDoktor argued that the conduct constituted an anti-competitive agreement, infringing Article 101 TFEU, as well as an abuse of Google’s dominance which Germany allegedly aided and abetted, infringing Article 102 TFEU (and national equivalents).

The court rulings

Following a joint oral hearing in January 2021, on February 10th, 2021, the Court ruled in favor of NetDoktor. By way of preliminary injunctions, the Court prohibited the GMH from making available to Google content of gesund.bund.de and from allowing the use of such content for the purpose of displaying Health Knowledge Panels. Google was ordered to refrain from displaying the content of gesund.bund.de in Health Knowledge Panels if based upon an agreement to prominently display such Panels. As a result, Google ceased displaying Health Knowledge Panels the same day.

The Court determined that NetDoktor had a claim for such an injunction because the cooperation between Google and the GMH constituted an agreement between undertakings that restrains competition to the detriment of competing health portals. The Court did not have to decide whether the conduct also constituted an abuse of dominance.

Agreement between Google and the German Ministry of Health

The Court found that Google and the GMH had entered into an agreement that the envisaged Health Knowledge Panels would permanently be filled exclusively with content of, and a link to, the portal gesund.bund.de. While both parties denied any binding contract between them, the Court emphasized that a common will is sufficient to establish an “agreement” under Article 101 TFEU. It found that the statements given at the joint press conference by Google and the GMH to announce their cooperation evidenced such a common will. Indeed, the parties expressed their understanding that Google’s preferential display of Health Knowledge Panels would render the GMH’s portal the first port of call for health information online.

GMH acts as "undertaking" when operating the portal gesund.bund.de

The Court ruled that by operating the portal gesund.bund.de, the GMH was acting as an “undertaking” in the meaning of Article 101 TFEU.

The Court pointed out that in European competition law,[3] the concept of an “undertaking” covers any entity engaged in an economic activity, regardless of its legal status or the way in which it is financed. An economic activity would not require that the entity provides its goods and services against payment, at least not if other companies in the market receive payments. Where an authority pursues an activity in the public interest, its economic character depends on whether such activity falls within the exercise of public powers or whether it can be disconnected from such powers.[4]

Based upon this legal analysis, the Court stressed that the services provided by gesund.bund.de are functionally interchangeable with health services operated and monetized by private companies such as NetDoktor. The operation of health portals had not previously been, and was not necessarily, carried out, by public entities. Accordingly, the GMH’s activities would have an economic character. A participation in economic activities would not cease just because a public authority also intends to fulfill public tasks.

Anti-competitive effects of the agreement

The Court found that the agreement restricted competition in the separate market for online health portals. The market is downstream to the market for general search services which Google dominates with a market share of above 90%. Both markets are closely related because more than 80% of users find their way to online health portals via Google Search, where they commence their online journey. Accordingly, in order to attract users and in turn advertising customers, operators of online health portals are particularly dependent on a good visibility on Google's search results pages. In the past, health portals had the opportunity to reach the top of the search results pages via competitive means. They could either provide particularly relevant content and use further measures to optimize their ranking in generic search results, or they could purchase ads at the top of the results page. Following the agreement, the Health Knowledge Panel appeared next to or on top of generic search results. Such boxes were exclusively reserved for the content of gesund.bund.de. Thus, while the Health Knowledge Panel was highlighted at the newly created position ‘0’, by default, this position was not available to competing health portals.

As a result of the prominent display of Health Knowledge Panels, competing health portals would lose traffic and, due to their two-sided business models, in turn also advertising customers. This would leave competing health services with less means to invest in their services and threaten their viability.

Thus, the Court considered it “obvious” that as a result of the challenged agreement, NetDoktor would suffer significant competitive disadvantages: “A central marketing instrument is withdrawn from competition and through the determined ‘pole position’ the defendant is granted a competitive advantage that cannot be compensated otherwise.” It would reflect both behavioral economics (as explained in Google Search (Shopping) decision[5]), and general life experience that consumers are more inclined to navigate to the most prominently displayed search results on a given results page.

This conclusion was supported by NetDoktor’s declining click-through rates on Google Search. The decline indicated that many users abandoned their search due to the Health Knowledge Panels, as their need for information had already been satisfied. Moreover, with keyword targeting being its primary marketing tool, NetDoktor’s monetization capabilities would be severely impacted by a visibility drop in even narrowly themed keyword areas (rather than across all keywords for which it ranks).

No exemption for efficiency reasons, Article 101(3) TFEU

The Court also ruled that Google and the GMH had not demonstrated any objective advantages that would justify an exemption pursuant to Article 101(3) TFEU.

The Court acknowledged that, in general, the introduction of product amendments and improvements corresponds to the competition concept of performance. However, according to the Court it was doubtful whether the inclusion of syndicated content constituted an improvement of a search engine. Essentially, it would be less of an improvement of the search engine than a shift of Google’s activity to another market, namely that of a publisher or other provider of content that is not completely opinion-free. Google thereby transcended its basic function as a search engine, which is to match users searching for products or services (e.g., information) and the respective providers, but also went beyond directly answering factual search queries (e.g., weather, height of the Eiffel tower). The Court found that Google had left the market for search engines in the sense of an intermediary of products and users and had become a provider of that product itself.

Moreover, by permanently placing the info boxes with the content from gesund.bund.de above generic search results, Google had evaluated the different sources available online to answer a search query in a way that pre-selected and highlighted one of those sources as the relevant answer. Such pre-selection was detached from Google’s relevance-based algorithms. With this nontransparent pre-selection, a material evaluation of the relevant content was made, which in turn contributed to the formation of public opinion. The Court concluded that, objectively, it would appear at least doubtful that this constituted an improvement of a search engine.

In the Court’s view, a more attractive design of a single supplier’s product for consumers may not compensate for the anti-competitive disadvantages that it created for all other market competitors. This would be especially true when a dominant company acts as gatekeeper on the upstream search engine market and, to the detriment of the private competitors that are dependent on it, permanently grants the pole position to a tax-funded offering by the state in the battle for user attention in order to improve the attractiveness or visibility of its own products: “In this case, two players, who are themselves taking a lower economic risk, are intervening in the relevant market and are making it more difficult for existing market players to access their users.” Any potential benefit in improving the population’s general health education would not justify the risk of driving other reputable providers of health information out of the market. On the contrary, the Court found, that this threatens the existing diversity of high-quality health portals and thus also the availability of second medical opinions.

Assessment

What if there had been no agreement?

The existing agreement between Google and the GMH regarding the ranking of gesund.bund.de allowed the Court to base its judgment upon Article 101 TFEU (and its national equivalent). However, the Court’s reasoning suggests that even in the absence of such an agreement, it might have found that the preferential ranking of gesund.bund.de infringes competition law – by constituting an abuse of Google’s dominant position on the market for general search services.

Google dominates most national markets for general search services. Under EU competition law, it constitutes an abuse of dominance if an undertaking distorts competition in a downstream market by strengthening the competitive position of a particular business partner in terms of its costs and revenues in relation to its competitors.[6] This is the case even if such secondary line discrimination does not strengthen the competitive situation of the dominant undertaking itself.[7] According to the Google Search (Shopping)[8] precedent, it also constitutes an abuse if a dominant undertaking favors its own business in a separate but closely related downstream market.

In NetDoktor, the Court described two relevant acts of preferencing. To the extent that users click on a link at the bottom of a Health Knowledge Panel that lead to gesund.bund.de, this state-run portal is favored. However, Google also favored a service of its own. The Court found that providing Knowledge Panels with rich health content directly answering corresponding search queries is capable of satisfying a demand for health information that is distinct from that for general search services. By offering such service, Google was itself entering the market for health portals. Accordingly, by prominently positioning and displaying its own Health Knowledge Panels to cater to the distinct demand for health information, Google was in effect not just favoring the source of the displayed information (gesund.bund.de) but also its own, newly created health portal.

For the same reasons that the Court denied any efficiency defense pursuant to Article 101(3) TFEU, it would be difficult to see how such preferencing could be objectively justified. The mid to long-term disadvantages for consumers resulting from the distortion of competition on the downstream content market might outweigh any potential short-term advantages for consumers in terms of a better presentation in search results pages of those content providers that will be left.

What about other types of favored content?

The case dealt with the display of Health Knowledge Panels. However, the same rationale relied upon by the Court also applies to other Knowledge Panels, OneBoxes, Units or equivalent groupings of content or links that Google compiles and displays within its general search results pages. The crucial question is whether Google, with the offering of such groupings, itself enters a market that is separate from that for general search services. In this respect, the Court drew a relevant distinction. It stated that the provision of “lexical or editorial, in any case of content that due to a conscious reduction is not entirely free of opinion,“ would “go beyond the fundamental function of a general search engine of connecting demanders for products or services (e.g. information) with suppliers online, but also beyond the direct answering of factual search queries (e.g. weather, height of Eifel Tower).“ With this distinction, the Court distanced its ruling from the only two decisions[9] that – prior to the EU’s Google Search (Shopping) ruling – had ever considered the favoring of Google’s own particular content within general search results as permissible, and which Google also relied upon in this case. Those two cases related to Google’s display of weather information and maps. In the absence of an established demand for comparing such factual content, there was no corresponding specialized downstream market that could be distorted. In contrast, it can be argued that where a market for particular content exists because there is not just one right answer, a dominant general search service may not reserve this market to itself by integrating corresponding content directly within general results pages.[10]

What if the favored portal had not been state-run?

The fact that the favored portal gesund.bund.de was provided by the state triggered two issues that would have been absent if the portal was operated by a private company.

First, the involvement of the state begged the question as to whether there was an agreement between “undertakings” as required by Article 101 TFEU. In case of a private operator, this would have been (even more) apparent.

Second, the state involvement played a role in the defendants’ efficiency defense. The GMH argued that consumers searching for health information would be better off if Google displayed content from the national health portal. This argument rested upon the presumption that a state-run portal is more independent and trustworthy than private providers which, in theory, could be subject to conflicts of interest due to the presence of advertising customers. The Court rejected this defense. It did not do so because a presumption in favor of state-run portals would undermine and threaten the free press (as could possibly also be argued). The Court rejected the efficiency defense because the potential benefits for consumers in terms of finding reliable information as easily as possible would not outweigh the likely disadvantages in the form of less choice and less relevant content as a result of foreclosed competition. Accordingly, if gesund.bund.de had been run by a private operator, the case for banning the cooperation would have been even stronger. Conversely, because the Court did not grant private intermediaries a carte blanche to favoring state-provided content, the judgments might be seen as an important clarification in securing a free, private press as a fundamental pillar of democracy.[11]

Lessons for the specific regulation of Big Tech?

The judgments touch upon some core questions relating to the current global debate on the most suitable regulation of digital gatekeepers. Three points can be made:

First, the Court’s well-reasoned imposition of interim measures within less than three months demonstrates once more the crucial role that private enforcement of competition-related obligations can play – beyond just damages. When public enforcement authorities, due to other priorities, remain inactive, civil courts can be a resort for affected parties to obtain interim relief before irreparable harm is caused. The judgments thus provide further arguments why legislators need to ensure that obligations for digital gatekeepers may also be privately enforced by businesses adversely affected by the conduct.[12]

Second, the case sheds light on the necessary scope of legislative bans for gatekeepers to favor particular services. The case shows that a gatekeeper may not only gain anti-competitive advantages from favoring its own downstream service, but also from promoting a particular third party with which it co-operates commercially. An effective prohibition of differentiated treatment must therefore cover both: the preferencing of an own service and the preferencing of one or several third parties to the detriment of their competitors. Moreover, the Court’s clear rejection of Google’s efficiency defense may support the calls for a per-se illegality of gatekeepers’ self-preferencing practices,[13] or at least for a reversal of the burden of proof for such conduct having no long-run exclusionary effect.[14]

Third, for the broader objective of securing media diversity and plurality, the Court’s critical observance regarding Google’s shift into publishing markets appears relevant. The Court rejected the idea that a digital gatekeeper is improving its intermediation service for consumers if, instead of matching supply and demand for opinion-forming information on the basis of relevance algorithms, the gatekeeper starts to hand-pick particular information providers and/or satisfies the demand directly with content that it controls. The underlying rationale is that where an intermediary has a strong impact on the formation of public opinion, in order to prevent irresolvable conflicts of interest that may result in a misleading of consumers, the intermediation service should be operated independently from the provision of relevant content. This notion justifies calls for a full intermediation neutrality of vertically integrated media gatekeepers or even a structural separation of intermediation and provision of content. The objective of media plurality also justifies a closer scrutiny of any co-operations between gatekeepers and content providers regarding their indexation and display.

Outlook

The “spectacular”[15] judgments by the Munich Court in the NetDoktor case demonstrates that private competition enforcement in the EU is alive and kicking. With the increasing dependence of businesses on online intermediaries, we are likely to see more litigation of this type, particularly on the blocking or suspension of accounts and the indexing, ranking, and display of competitors. This should, in general, be welcomed as private enforcement may serve as a crucial supplement where public enforcement falls short of providing speedy and effective outcomes.